Lessons: Hosea 11:7-9; Romans 6:1-11; Matthew 18:15-35

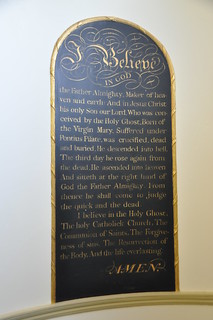

We are now approaching the end of the Apostles’ Creed. The last section reads: [I believe in] “the Holy Spirit, the holy catholic church, the communion of saints, the forgiveness of sins, the resurrection of the body and the life everlasting. One week to go after this! But here is a question: why is “the forgiveness of sins” placed here, next to last? Why not earlier in the Creed, which speaks of Christ’s atoning death? Stick with me as I try to unravel something of this mystery.

If there is anything crystal clear in the Bible, it is God’s determined will to forgive. In the Old Testament, the Lord God announces Himself a God of justice and a God of mercy. From Mount Sinai God says of Himself:

I the LORD your God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children to the third and the fourth generation of those who hate me, but showing steadfast love to thousands of those who love me and keep my commandments.” (Exod 20:5-6)

The history of God’s people Israel is one of testing this steadfast mercy by steadfast rebellion. Time and time again, from the Wilderness generation through the period of the judges to the four centuries of Israel’s monarchy, the people turned away from God to worship idols. All this as He warned them of the consequences through the succession of prophets.

One of the first writing prophets was Hosea. Hosea’s own tragic marriage to a prostitute became the prism through which he likened Israel’s broken covenant with God, and God reacts to this spiritual adultery with the righteous anger of a betrayed partner. At the same time, through Hosea God reveals something of His inmost heart. It comes in our reading today from Hosea chapter 11. In this chapter, God is, in effect, talking with Himself. In His indignation over against Israel’s idolatry, He contemplates destroying the nation utterly, as He did in the days of Abraham and Lot with the so-called “cities of the plain,” which included Sodom and Gomorrah and the lesser-known Admah and Zeboiim. But then the Lord interrupts Himself, saying:

How can I give you up, O Ephraim? How can I hand you over, O Israel? How can I make you like Admah? How can I treat you like Zeboiim? My heart recoils within me; my compassion grows warm and tender. I will not execute my burning anger; I will not again destroy Ephraim; for I am God and not a man, the Holy One in your midst, and I will not come in wrath. (Hos 11:8-9)

Here, as in the Servant Songs, we glimpse the unfathomable heart of God. He is prepared to set aside the persistent high-handedness of His people and to do so because He is God not man. Have you ever considered how strange it is that the tiny Jewish nation, which has never held power on the world stage, is still here. Where are the Assyrians, the Babylonians, the Greeks or Romans, the Mongol hordes, today? I think it is God’s steadfast love, His covenant love to Israel, that has been at work to preserve the Jewish people despite their persistent callowness (the majority of Jews in Israel today are secular) and the persistent history of anti-Semitism.

This is the same heart of the God who loved the world so much that He sent His Son into the world to suffer and die for us. If there is one thing we know about Jesus, it is that His message and His ministry was one of forgiveness from start to finish. In one of his first miracles, He said to the paralyzed man on a stretcher, “Your sins are forgiven,” and followed up by healing him. He taught His disciples to pray, “Forgive us our sins, as we forgive those who sin against us” and ordered them to forgive their brothers not seven times but seventy-times-seven. In the Parable in our Gospel today about the unforgiving steward, the sternest warning falls on unforgiveness and the failure of love for the neighbor that lies behind it. Finally, from the Cross, Jesus prayed for His persecutors: “Father, forgive them for they know not what they do.”

Now let’s return to the Creed. The first two sections of the Creed describe the mighty acts of God “for us and for our of salvation,” as the Nicene Creed puts it. The third section is about how we receive, how we appropriate that salvation. Is it not self-evident that we receive Christ into our hearts by grace through faith? Well, I think the answer to this question is Yes and No. Yes, we are born again and saved through faith alone, by putting our trust in Jesus and Him alone, as most Protestants affirm. But we are saved by faith in a context, and the context is the community of the church, the real-life visible church, united in love by the Holy Spirit. And the external sign of our entering the church is baptism.

The Apostles’ Creed and the Nicene Creed differ at this point. While the Apostles’ Creed says, “I believe in the forgiveness of sins,” the Nicene Creed adds: “We confess one baptism for the forgiveness of sins.” Note the change from “I believe” (Latin credo) to “We believe.” The Apostles’ Creed was aimed at individuals coming to baptism, while the Nicene Creed was the confession of all members together as the Church. In the early church, adult converts were baptized naked in a separate hall called a “baptistery.” Coming out of the water, they were clothed in white and brought into the main church to participate fully in the life of the congregation. Taken together, the Creeds make clear that baptism is as symbolic rebirth in the life of the believer in the context of the church. Receiving the forgiveness of sins is not a license to wander lonely as a cloud on Sunday in the woods, listening to the birds singing hymns in the trees.

The connection between baptism and forgiveness goes back to the person of John the Baptist. His father prophesies about John, saying: “You, child, will be called the prophet of the Most High; for you will go before the Lord to prepare his ways, to give knowledge of salvation to his people in the forgiveness of their sins” (Luke 1:76-77). And this is precisely what John did. Jesus Himself was baptized by John in the Jordan, and He commanded His apostles to preach the Gospel to all nations, baptizing them and instructing them in all He had taught them.

And this just what the apostles did. In our Epistle today, Paul makes clear that baptism is the context of repentance and faith when he says: “We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death, in order that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life” (Rom 6:4).

The Anglican Church, which followed the main current of Reformation teaching, defines baptism this way (Article 27 of the Articles of Religion):

Baptism is not only a sign of profession, and mark of difference, whereby Christians are discerned from others that be not christened, but it is also a sign of Regeneration or new Birth, whereby, as by an instrument, they that receive Baptism rightly are grafted into the Church; the promises of forgiveness of sin, and of our adoption to be the sons of God by the Holy Ghost, are visibly signed and sealed; Faith is confirmed, and Grace increased by virtue of prayer unto God.

Almost all Christians agree that baptism is a sign of some sort, but what kind of sign? Some see it as a mere sign, like a paid-up membership card or (maybe for today’s generation) like a tattoo that says, “I was saved on such and such a date.” Anglicans believe that it is more than that, it is a sign of a regeneration and transformation which begins with conversion and continues throughout one’s life. For this reason, baptism is a once-for-all comfort and assurance in times of doubt and temptation. Martin Luther, who made faith the heart of the Gospel, also went through many spiritual struggles, and he concluded: “The only way to drive away the Devil is through faith in Christ by saying: ‘I am baptized, I am a Christian.’” Baptism and faith are two sides of the coin of salvation.

Forgiveness was signed and sealed once for all on the cross of Calvary. Forgiveness is sealed once for all in our lives when we are born again of water and the Spirit. And forgiveness continues throughout our Christian life to the end. It is the key to personal relationships in marriage and the family. Dietrich Bonhoeffer in his wedding sermon – which Peggy and I had read at our wedding fifty-four years ago – says to the couple:

Don’t insist on your rights, don’t blame each other, don’t judge or condemn each other, don’t fault with each other, but accept each other as you are, and forgive each other every day from the bottom of your hearts.

Forgiveness in marriage, I think, includes not only things done to one another but holding against one another illusions of what the other person can never be. Sometimes it is only by kissing the toad that we discover the prince, or the princess.

In the church, forgiveness includes accepting difficult and needy persons and, so it seems in our day, in resisting the temptation to judge others based on their political opinions. Forgiveness means welcoming the stranger into our midst, that neighbor who is not the person we would choose to associate with but the person for whom Christ died: the poor, the homeless, the prisoner, the social outcast.

Forgiveness is the heartbeat of Christ. It is also the heartbeat of the Church, which testifies to this forgiveness in the sacrament of holy baptism.

I mentioned last week that the Laying-on-of-Hands service planned for September 19 will include two opportunities for baptism, one on September 12 at the park and as part of the service on the 19th itself. In the context of these baptisms, we shall be reciting the Apostles’ Creed together. Let’s not think of this as a mere formality but as an occasion when we as the church can celebrate heartbeat of God in our midst, as we welcome the newly baptized with this affirmation:

We receive you into the fellowship of Christ’s Church. Confess the faith of Christ crucified, proclaim the resurrection, and share with us in the royal priesthood of all his people. (BCP 170)

As we welcome them, let us also be thankful that we are forgiven sinners and vow to extend the heartbeat of Christ to all our neighbors, for whom Christ died.

Illustration: The Baptism of St. Paul, Capela Palatina, Palermo (Wikimedia)