Lessons: Psalm 51:1-12; Acts 8:4-8,12,14-17; John 3:1-16

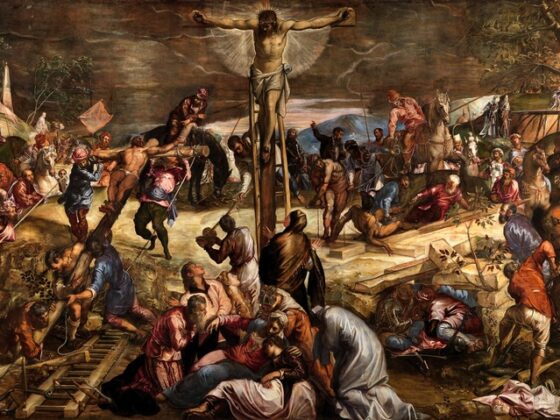

The Apostles’ Creed, as we have noted, is Trinitarian in shape and moves swiftly from naming God the Father, creator of heaven and earth and naming Jesus Christ, the Son of God, to the longer central narrative of Jesus’ earthly work: conceived by the Holy Spirit and born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate, crucified, dead and buried, risen on the third day, ascended into heaven to God’s right hand.

Now we come to a third and final section of short phrases, which reads:

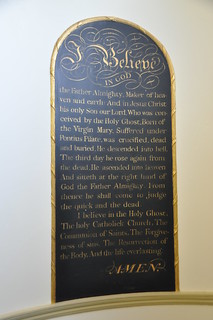

I believe in the Holy Spirit, the holy catholic church, the communion of saints, the forgiveness of sins, the resurrection of the body and the life everlasting.

At first glance, this section might seem a grab-bag of miscellaneous doctrines, but at closer look it is held together by the Person of God the Holy Spirit. This section is also, for the first time in the Creed, about us – “us” individually and corporately as the church. So I have titled this sermon: “The Holy Spirit, God in us.”

Of the many mysteries of the Triune God, the identity of the Holy Spirit is especially mysterious. In our mind’s eye, we can imagine God the Father and God the Son, because we all have experience of fathers and sons, and we can definitely imagine the historical Jesus, because he is portrayed at some length in the Gospels. But the Holy Spirit is almost by definition inconceivable. Jesus Himself said of the Spirit: “The wind blows where it wishes, and you hear its sound, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes” (John 3:8). The closest the Bible gets to an image of the Spirit is that of a dove, but we know immediately that this is a metaphor for its movement, not its identity. (One can use “it” or “he” or even occasionally “she” for the Spirit because the Spirit is “neuter” in a way the Father and the Son are not.)

None of this is to say that the Holy Spirit is not a real Person of the Trinity, only that he is hard to visualize. Let me try out an analogy between the divine Spirit and the human soul. Ask this question: “who am I?” Geneticists may chart the human genome; neuroscientists may map the synapses of the nervous system and areas of the brain; computer scientists may design “artificial intelligence” programs that can talk to us and beat world masters in chess, but none of this expert knowledge explains the reality of the soul, that invisible source of our identity as creatures made in the image of God.

With great caution, I would say that the Holy Spirit is something like the soul of the Triune God. The human soul is the source of life, of dynamism, of motivation. So also God is the “living God,” the God of power, and above all, the God of love, and the Holy Spirit is particularly associated with these attributes: life, power and love.

The great church theologian Augustine spoke of the Holy Spirit as the mutual love which flows between the Father and the Son, and the Nicene Creed speaks of the Spirit as “proceeding from the Father and the Son.” There is a sense in which the Persons of the Trinity indwell each other, and this is why can speak of the Spirit of God or the Spirit of Jesus, knowing that the Father and the Son are fully present when we experience the Holy Spirit. We seldom pray to the Spirit directly but rather pray in the Spirit; rather, we invoke him, saying “Come Holy Spirit.”

This is as far as I dare go in explaining this unique Person of the Holy Trinity. But there is one other unique aspect of the Spirit as we experience Him. He is in us, individually and corporately. From the beginning God breathed into man the breath of life, and we naturally continue to think of living and dying in terms of breathing. God’s spirit is intimately present in every soul alive and is at the same time inexhaustibly available to millions of others at the same time. Excess population may be a problem for politicians; it is not a problem for God!

But the hope of eternal life with God was lost when our first parents tried to grasp the fruit of the tree for themselves, and this original fall is repeated in all our lives. “As in Adam, all die” (1 Cor 15:22). For this reason, David, after his sin with Bathsheba, cries out:

Create in me a clean heart, O God, and renew a right spirit within me. Cast me not away from your presence, and take not your Holy Spirit from me. Restore to me the joy of your salvation, and uphold me with a willing spirit. (Psalm 51:10-12)

Nothing but a new creation and a new Adam will do to restore salvation, which is why Jesus says to Nicodemus: “unless one is born again, he cannot see the kingdom of God.” When Nicodemus objects, “How can a man be born when he is old?” Jesus repeats: “unless one is born of water and the Spirit, he cannot enter the kingdom of God.” “That which is born of the flesh is flesh,” Jesus says, “and that which is born of the Spirit is spirit” (John 3:5-6). The sovereign work of the Holy Spirit is called regeneration, i.e., rebirth, not to this life in the flesh but to eternal life with God in the Spirit. And the sole condition for this rebirth is receiving God’s love by faith. “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life” (John 3:16) – a verse which I trust you all know.

Jesus’ reference to water and the Spirit suggests that regeneration has an outer accompaniment, which is baptism in water. After the Spirit descends on the day of Pentecost, Peter concludes his sermon with this appeal: “Repent and be baptized every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins, and you will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit” (Acts 2:38). These three responses – faith, baptism, and receiving the Spirit – are the normal pattern of conversion, but they may occur in different order. In our reading today from Acts chapter 8, we see one of these irregularities. The Samaritans, you will recall, were alienated from the Jews, but when Philip went down to Samaria and preached with signs and wonders, the Samaritans believed the Gospel and were baptized, but for whatever reason they did not receive the Spirit. Acts goes on to say:

Now when the apostles at Jerusalem heard that Samaria had received the word of God, they sent to them Peter and John, who came down and prayed for them that they might receive the Holy Spirit, for he had not yet fallen on any of them, but they had only been baptized in the name of the Lord Jesus. Then they laid their hands on them and they received the Holy Spirit. (Acts 8:14-17)

My own guess is that God wanted to make clear for all times and peoples that the Gospel and the Spirit were now available to every race and culture – to Jew, Samaritan, and Gentile – and that these different groups were united by the Spirit in the one apostolic faith. (A similar thing happened in Acts chapter 10 when the Holy Spirit fell on the first Gentile converts before they believed and then they and their houses were baptized.) Note also in this episode in Samaria, the physical laying-on-of-hands accompanied the full baptism in the Spirit. This is the precedent the church has used in the rite of confirmation.

So let me stop here and say a word about baptism as the external sign and seal of the Holy Spirit. In the early church, which experienced mass conversions, baptism usually followed repentance and faith, but as more and more households came to faith together, baptism of infants and young children came to be practiced and even later became the norm. In the case of infants, the sacrament preceded adult faith; that faith was promised by parents and godparents. I do not think the Bible teaches a causal power to baptism (which is what Roman Catholics teach), but baptism conveys a promissory power to bring a child to the fulness of faith and of the Spirit. At baptism, God, I believe, plants a seed of the Spirit in the hearts of believers’ children, which they may cultivate or neglect but which remains sown throughout their lives. So Anglicans may delay baptism for young children, but they do not practice re-baptism.

There is a second external manifestation that accompanies the Spirit, and that is “testimony.” The Risen Jesus’ final words to His apostles are: “You will receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you, and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the end of the earth” (Act 1:8). One of the most common words in the Acts is “testify” or “witness” – the Greek word for these is “martyr.” To be filled with the Holy Spirit is to be a martyr, and to be a martyr is to confess Jesus publicly. St. Paul says this about salvation: “if you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved” (Rom 10:9).

Public confession of Jesus is thus intimately linked with baptism and the creeds. In fact, the Apostles’ Creed first developed as a kind of Q&A session at baptism. If you look at the baptism service in the Anglican Prayer Book (pages 186-187), you will see the original setting. The bishop or priest asks three leading questions: “Do you believe and trust in God the Father?” “Do you believe and trust in Jesus Christ?” “Do you believe and trust in the Holy Spirit?” And the candidates answer, “I do,” and then recite that portion of the Apostles’ Creed.

Of course, baptism and confirmation are merely the outward sign of the Spirit’s inner work, which is called sanctification. The Holy Spirit is integral to the spiritual disciplines, what one writer calls “a long obedience in the same direction.” To read the Bible effectively means not only to believe that it is the inspired and set it on the coffee table, but to read it expectantly believing that the Spirit continues to speak to us through God’s Word written. When we pray and praise with our minds – e.g., using said prayers from the Prayer Book or through psalms and hymns, the Holy Spirit is lifting our thoughts and voice to God. There is also a kind of non-verbal communication of the Spirit, either in silent meditation or ecstatic speaking in tongues in which we may participate in the depths of God.

Let me conclude with a further piece of my – I should say my and my wife’s – personal testimony. I have already said that I was a convert to Christ at age twenty while Peggy was a cradle Episcopalian. A couple years after my conversion, we both experienced “baptism in the Spirit” in the charismatic renewal in the Episcopal Church, which included our asking for the anointing of the Spirit with speaking in tongues. (BTW, Anglicans have never accepted the Pentecostal idea of a second spirit-baptism as necessary for the full Christian life. Indeed, some people experience something like a “second blessing” more than once. Anglicans believe there is in principle only one baptism (Eph 4:5), although as in the Book of Acts people’s experience of the one baptism may be quite varied.) Anyway, looking back now on fifty years, Peggy and I both see this time as a critical moment in our walk, even as glossolalia, as it is called, has become less important in our daily lives.

During the next few weeks, we at Redeemer as a church will be preparing for the service on September 19 when Bishop Minns will come for the Laying-on-of-hands, a service of confirmation, reception and renewal of vows. It is my hope and prayer that you will all, as individuals and a congregation, seek this occasion for a new infilling of the Spirit in your lives, wherever you are along the road of salvation.

The Bible ends with these words: “The Spirit and the Bride say, ‘Come.’ And let the one who hears say, ‘Come.’ (Rev 22:17). So I too conclude: Come, Lord Jesus! Come, Holy Spirit, come!