On Ash Wednesday this year I attended my parish church and was marked by the priest with the sign of the cross, along with the words: Remember that you are dust and to dust you will return. As powerful as the symbolism of the act is, the words fell flat.

Or is it just me recalling the old wording: Remember, O man, that thou art dust and to dust thou shalt return? The priest pausing mid-sentence – O man – and addressing each worshiper as “thou,” rather than gliding past with an indeterminate “you.” Each of these “thou’s” shares a common humanity: all are man, heirs in sin of the one earthly father and heirs in Christ of the one Heavenly Father. But it had to go, because the sin and shame of “man,” so we are told, is actually the sin and shame of “mansplaining.”

Surely one can find a substitute for O man. O person? O human? O differently gendered? Failing that, just move on to O-mit. Hence the Anodyne Standard Version, which must be authoritative because it bears the imprimatur of the International Council on English Liturgies.

“But the Millennials simply don’t get it?” Well, if as they say, praying shapes believing (lex orandi, lex credendi), it is equally true that believing shapes praying. And how shall they hear without a preacher? If “O man” is so obviously scandalous in our day, would it really be too much for the priest to give an explanation when inviting the people to the altar rail? Perhaps, he might instruct them, bearing the name of Adam is of a piece with bearing the cross on one’s brow.

My goal in this essay is to make a case from Scripture for traditional language for man and for understanding how men and women, each in a particular way, are “image-bearers” of God. In this whirlwind tour of the Bible, I shall focus on the foundational texts in Genesis, the Gospels, and the Letters of St. Paul.

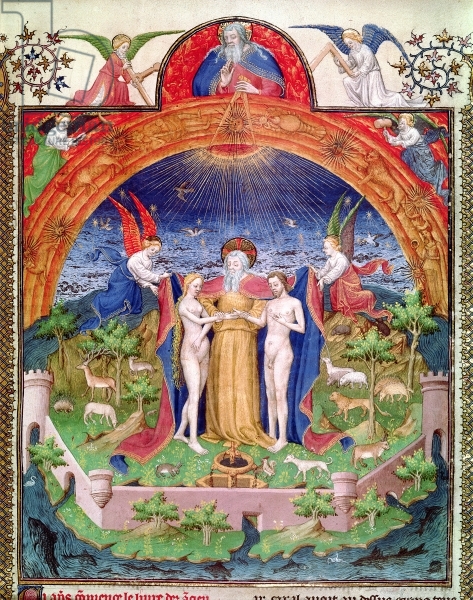

Creation and Fall: From Man to Adam

We begin at the beginning with language for God and man: “So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them” (Genesis 1:27). Right at the outset, let’s note: grammatical gender and number do not always correspond to the referent. This is true in all gendered languages. So in this verse, the one God of Israel (’elohim) is grammatically plural. In Hebrew, “spirit” (ruach) can be grammatically feminine or masculine, and in Greek it is grammatically neuter (pneuma). It is also true that gendered nouns, pronouns, and verbs often do indicate how the referent is conceived.

“God created man in his own image.” God is uniformly indicated in both Testaments with masculine pronouns, as is the Spirit on occasion (John 4:24). Grammatical gender aside, the masculinity of God as revealed in Scripture is beyond dispute: the Son makes the Father known (John 1:18), and He is addressed by Jesus and the Holy Spirit as “Abba, Father” (Luke 14:36; Romans 8:15; Galatians 4:6). The Triune God, while not a male (Numbers 23:19), is masculine, and any attempt to imagine a gender-fluid deity is simply idolatrous.

Secondly, the Hebrew word for “man” (’adam) occurs grammatically in the singular only. There are no Adams nor Adamses in the Bible. Since the first chapter of Genesis is describing the different “kinds” of God’s creatures, it is proper, I think, to translate the word as “man-kind.” Just as other verses in this chapter describe different creatures propagating “according to their kind,” so Genesis 1:27-28 specifies that mankind comes in two sexes, “male and female,” by which means they are commanded to “increase and multiply” sexually.

Each of the creation narratives has a climactic moment. In Genesis 1, it is God creating mankind in his own image. In Genesis 2, it is the male recognizing his female counterpart. Yet Genesis 2 retains the use of the noun “man” for the first human being:

Then the LORD God formed the man (ha-’adam) of dust from the ground (’adumah) and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living creature. (Genesis 2:7)

In this case, “the adam” is both an individual male (Adam) and a generic type (Man). His nature is twofold, with an earthy body (note the Hebrew word-play between “adam” and “earth,” similar to “human” and “humus”) and a spiritual soul. As the narrative progresses, this solitary Man finds no counterpart in the animal world, so God “builds” from his body “the woman.”

Then the man (ha-’adam) said, “She (“this one”) at last is bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh; she shall be called woman (ha-’ishah), because she was taken out of man (ha-’ish).” (Genesis 2:23)

“Mankind” is now seen in terms of two inter-related sexes referred to with the word-pair “’ish and ’ishah,” “man and woman,” (in Hebrew, as in English, the feminine noun is derived from the masculine). The next verse completes the story of Adam in search of a wife with this moral: “Therefore a man shall leave his father and his mother and be joined to his wife, and they shall become one flesh” (Genesis 2:24). Man’s nature is now perfected in the one-flesh union of husband and wife that will lead to the propagation of humankind. Despite this differentiation of the sexes, the Man continues to head the new family: “And the man (ha-’adam) and his wife (ha-’ishah) were both naked and were not ashamed” (Genesis 2:25).

This pattern of representation continues after the Fall. The Lord God calls the Man to account saying: “Where art thou?” God proceeds to judge each malefactor in the Fall individually, but the Man receives the final sentence of death on behalf of mankind, both sexes, present and future.

With the Fall, we see the morphing of the generic name “Man” into the personal name Adam, which is complete by the end of chapter 4 (cf. 4:1 and 4:25). By chapter 5, Adam is clearly the personal patriarch of the human race:

This is the book of the generations of Adam. In the day that God created man, in the likeness of God made he him; Male and female created he them; and blessed them, and called their name Adam, in the day when they were created. (Genesis 5:1-2 KJV).

From now on, history will be patriarchal, with the passing on of the father’s name to the next generation.

The establishment of patriarchy does not mean that the woman has no part to play in the ongoing human history. Just as God had formed the first man out of the dust so that he became an animate body, now Eve will become the “mother of all living flesh” (Genesis 3:20). Every “son of man,” male and female, will be “born of woman” (Job 14:1; Matthew 11:11; 1 Corinthians 11:1-12). By subordinating her desire to her husband, she will bear earthly “seed” who will ultimately trample on the Enemy (Genesis 3:15-16).

Jesus, Son of Adam, Son of God

The pattern of Genesis continues into the Gospels. According to Matthew’s genealogy, Jesus is the promised messianic Seed from Eve through a lineage of fathers, from Abraham and David to Joseph of Nazareth. Matthew highlights the promissory character of the Seed by adding the names of the irregular mothers, Tamar, Rahab and Ruth, culminating in the Virgin Mary, Joseph’s betrothed, “of whom Jesus was born, who is called the Christ” (Matthew 1:16).

According to Luke’s genealogy, Jesus is “son of Adam, son of God” (Luke 3:38). He is son of Adam through Eve, and Son of God through Mary. Jesus is Very Man and Very God. Mary is his human mother, daughter of Eve. She is the Virgin Mother of Immanuel, who is conceived by the Holy Spirit. The Word is made Man, not from the will of a human father but from God (cf. John 1:13).

The New Testament has two Greek words for man. The word anēr generally is used for a particular man; the word anthrōpos generally refers to mankind or a typical man (e.g., Luke 15:4). “Son of man” is a synonym of “man” in Old and New Testaments, with a special sense of the transitory lifespan of “mortal man” (Job 25:6). Jesus frequently uses the title “the Son of Man” in speaking of his own humiliation and exaltation (Mark 10:45; 13:46).

Beneath Jesus’ usage of “Son of Man” lie two key biblical texts: Psalm 8 and Daniel 7. The Psalmist ponders the mystery of God’s favor in over-reaching the angelic hierarchy and choosing mortal man as his royal covenant partner:

When I look at your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars, which you have set in place, what is man that you are mindful of him, and the son of man that you care for him? Yet you have made him a little lower than the heavenly beings and crowned him with glory and honor. You have given him dominion over the works of your hands; you have put all things under his feet… (Psalm 8:3-6)

In Daniel’s dream vision, he sees “one like a son of man” enthroned by the Ancient of Days and given an everlasting dominion (Daniel 7:9-14). As in Psalm 8, a mortal man is exalted to the throne of God. The author to the Letter to the Hebrews resolves the mystery of humiliation and exaltation in the figure of Jesus’ royal priesthood, “crowned with glory and honor because of the suffering of death, so that by the grace of God he might taste death for everyone” (Hebrews 2:9).

The language of Christ’s mediatorial Manhood appears also in Paul’s testimony given to Timothy: “For there is one God, and there is one mediator between God and men (anthrōpoi), the man (anthrōpos) Christ Jesus, who gave himself as a ransom for all… (1 Timothy 2:5-6). Not surprisingly, the modern revisers of the Nicene Creed broke the link in the original Greek and traditional language that “for us men and our salvation… [Christ] was made man” by omitting “men.”

Jesus and the Brethren

It is unfortunate that “brethren” has fallen out of common usage and even out of modern Bible translations, because it captures a collective sense of the word “brother” which is inherent in the usage of Jesus and the apostolic church. Imagine a world without “children.”

While the Old Testament uses “brothers” to indicate the entire people of Israel in a patrilineal sense: “your servants were twelve brothers, the sons of one man” (Genesis 42:13), Jesus overturns this understanding in a striking metaphor of family identity:

While he was still speaking to the people, behold, his mother and his brothers stood outside, asking to speak to him. But he replied to the man who told him, “Who is my mother, and who are my brothers?” And stretching out his hand toward his disciples, he said, “Here are my mother and my brothers! For whoever does the will of my Father in heaven is my brother and sister and mother.” (Matthew 12:46-50; cf. 19:29)

For rhetorical emphasis, Jesus speaks particularly of “mother, brother, and sister,” but elsewhere he speaks collectively: “And the King shall answer and say unto them, Verily I say unto you, Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me” (Matthew 25:40 KJV). Actually “brethren” in this verse is not merely a collective plural but rather corporate plural, as Jesus is the invisible head of the needy body of brethren. To neglect or succor one brother is to do likewise to Him. Jesus’ usage was adopted by the apostles, who routinely addressed their fellow members of the Body of Christ as “brethren.”

St. Paul on Adam and Christ

St. Paul’s recapitulation of biblical history in “the light of the gospel of the glory of Christ, who is the image of God” (2 Corinthians 4:4) takes him back to the beginning, to the first man (anthrōpos):

Therefore, just as sin came into the world through one man, and death through sin, and so death spread to all men because all sinned – for sin indeed was in the world before the law was given, but sin is not counted where there is no law. Yet death reigned from Adam to Moses, even over those whose sinning was not like the transgression of Adam, who was a type of the one who was to come. But the free gift is not like the trespass. For if many died through one man’s trespass, much more have the grace of God and the free gift by the grace of that one man Jesus Christ abounded for many. (Romans 5:12-15; cf. Ephesians 2:15-16)

Paul interprets the role of the first “Adam” in two ways. There is the historical Adam, the first patriarch of the line to Moses and beyond; and then there is the prototypical man of Genesis 1-2. While Paul likely understood the spread of sin as having a genetic basis, his primary reference to Adam is in the second role “in that [or in whom] all men sinned,” which clearly includes Adam and Eve, males and females, down through history. Similarly, he sees Jesus as the Second Adam, the “one Man” through whom the grace of God abounded for many.

In his great chapter on the Resurrection, Paul makes clear that Jesus differs from the first Adam not simply in being a sinless man of dust, but as having a unique heavenly origin and destination:

Thus it is written, “The first man Adam became a living being”; the last Adam became a life-giving spirit. But it is not the spiritual that is first but the natural, and then the spiritual. The first man was from the earth, a man of dust; the second man is from heaven. (1 Corinthians 15:45-47)

The transformation of Jesus from the mortal to the immortal begins with his being born of a woman, a son of Adam; however, conceived by the Holy Spirit, He alone is empowered to become a life-giving spirit. Temporally, that transformation is completed with his death and resurrection: “For as by a man came death, by a man has come also the resurrection of the dead. For as in Adam all die, so also in Christ shall all be made alive” (1 Corinthians 15:21-22). For us, however, the transformation awaits fulfillment: “Christ the firstfruits, then at his coming those who belong to Christ” (verse 23).

Paul and the Image of God

Clearly the “image of God” is a central tenet in Paul’s teaching. The Son of God is, according to Paul, “the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation” (Colossians 1:15). He is the divine prototype, who, while in the form of God, put on the form of a servant, and in the “likeness of Man” humbled Himself to death on a Cross (Philippians 2:5-8). Believers, while still in the flesh, share his Risen Glory in hope: “Just as we have borne the image of the man of dust, we shall also bear the image of the man of heaven” (1 Corinthians 15:49).

In the above passages, Paul speaks generically of man (anthrōpos) in God’s image, irrespective of sexual difference. In one passage, however, he does elaborate on how male and female sexes – the man and the woman – participate in the image. In arguing that women in Corinth should wear a head-covering in worship (1 Corinthians 11:2-16), Paul states:

I want you to understand that the head of every man is Christ, the head of the woman is the man (anēr – ESV translates “her husband”) and the head of Christ is God” (1 Corinthians 11:3).

The operative word that distinguishes the divine Persons and the human sexes is “head” (Grk. kephalē). The head, as I interpret it, is the representative member or “icon” of corporate identity. Christ is the Head or “icon” of the new humanity, the Second Adam; the man (male) is the head or “icon” of the human family. The Father is not an icon but the primal Source (another sense of kephalē), the “font of divinity,” from whom all things take their being (1 Corinthians 8:6).

Conflating Genesis 1 and 2, Paul makes the point that in the beginning there was only one “adam” in God’s image:

For a man (anēr) ought not to cover his head, since he is the image and glory of God, but woman is the glory of man. For man was not made from woman, but woman from man. Neither was man created [to reflect Christ’s glory] for woman, but woman [to reflect man’s glory] for man. (1 Corinthians 11:7-9 with my additions)

In this particular context, “image” (Grk. eikon) represents and “glory” reflects. The man is the image and glory of God because he heads the human family and reflects God’s glory in Christ publicly, before God and man (cf. Luke 12:8). The man represents the human race, whereas the woman, formed subsequently, reflects back and fulfills the man’s own “glory” in the one-flesh union with him (“she now is flesh of my flesh”).

Paul’s argument here may raise the question, for modern readers at least: “You mean women are not made in the image of God?” I think Paul would reply: “I don’t care for the way you have phrased the question. Women and men both bear God’s image from the beginning, but each in a particular way.” Women share in God’s image “in Adam,” in mankind, and through baptism in Christ, the Second Adam, who is the true image of God (Galatians 3:28). Women reflect the glory of that image to their husband and bear that image through their children. This is what he does in effect say in verses 11-12:

In Christ, Woman is not complete without Man, nor is Man complete without Woman. For just as Woman reflects back to Man his primal image, so she bears his image physically through childbirth. So Man and Woman are both image-bearers; and all things are of God. (my paraphrase)

The delicate issue in Corinth has to do with how men and women, who bear God’s image equally but differently, interact when they step outside the family and into the assembled Body of Christ (cf. 1 Corinthians 14:34-35). Hence Paul’s argument in 1 Corinthians 11 is not some trivial defense of head-gear but an application of his Gospel, of his first principles, his tradition, of human nature in the image of God in Christ (see verses 2 and 16).

Image-Bearers in Marriage

The way in which male and female “bear” God’s image is not mutual in the sense of identical and interchangeable but complementary in the sense of distinctive and interconnected. (N.B.: The demeaning of the word “complementary” today is itself a sign of the politicizing of language which this essay addresses.) With this terminology in mind, we now turn to Paul’s teaching on the relations of husband and wife. In Ephesians 5, as in 1 Corinthians 11, there is a “hierarchy” of headship. The first half of the chapter concludes with thanks “to God the Father in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ,” which leads to the exhortation to “be subject to one another out of reverence for Christ” (Ephesians 5:20-21). Mutual submission in Christ takes a particular form in the relations of wives and husbands:

Wives, submit to your own husbands, as to the Lord. For the husband (anēr) is the head of the wife even as Christ is the head of the church, his body, and is himself its Savior. Now as the church submits to Christ, so also wives should submit in everything to their husbands. (Ephesians 5:22-24)

The Greek word translated “submit” (hypotassesthe) means taking one’s place in the divine plan of creation and salvation. The married couple images Christ’s saving relationship to the Church. The wife receives the man’s love and returns the glory of his image by honoring his headship. The model of wifely submission is not childish or slavish obedience (cf. Ephesians 6:1-4) but the gracious humility of the Virgin Mary: “be it unto me according to your word.” Her role is that of the church submitting to Christ her Head, who is preparing her as a spotless Bride (verse 27).

Paul goes on at greater length to exhort husbands likewise to find their place in this order: “Husbands, love your wives, as Christ loved the Church and gave himself up for her to make her holy, cleansing her by the washing with water through the word” (verses 25-26). The husband’s love is not worldly desire of the flesh but the perfect love of the Divine Bridegroom: “You are altogether beautiful, my love; there is no flaw in you” (Song of Songs 4:7). This is the costly love (agapē) that Christ demonstrated when He gave Himself up for the Church. The mutual subjection of husband and wife out of reverence for Christ is, St. Paul claims, a profound mystery (verse 32). The roles of husband and wife are distinct, fashioned on the created distinction of male and female yet conjoined in “imaging” Jesus Christ and His Church.

In this passage, Paul makes no reference to child-bearing and -rearing, but it is implicit in the instruction of children and the household that follows in chapter 6 (cf. Titus 2:3-5). The husband should aspire to be a provider and defender of his wife and children, but I am not sure that captures his distinctive role as representative head of the family. At the climax of the traditional Anglican wedding service, the priest says: “I now pronounce that they be Man and Wife together in the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit” (recent revisions have substituted “husband and wife”). As “man” the husband is to serve as Christ’s delegate on behalf of his family in the world. Not so many years ago, a wife would identify herself as “Mrs. Adam Jones,” even after her husband had died. She did not consider this a case of being “owned” by her husband or submerging her personality into his but being joined with him in one indissoluble unit – “Man and Wife together.” She bore his name with honor, as did the children she bore to him, just as he and she together with their children bore their baptismal names in Name of the Triune God. Names matter, to God and to us.

One could, I suppose, caricature the image of husband and wife in terms of a knight in shining armor and a damsel in distress. That is not Paul’s view. For Paul, all Christians are to put on the whole armor of God (Ephesians 6:11-20), which includes a kind of female militancy (“archery” in Narnia). Instances abound: the prostitute who gives false testimony to save her son (1 Kings 3:16-27); the mother who encourages her seven sons to die nobly for God’s Law (2 Maccabees 7:20-23). Then there are the prayer warriors like Anna, “worshiping with fasting and prayer night and day (Luke 2:37), and Helena and Monica, praying for their sons’ conversion. The Church has had its female monastics and martyrs, who have been honored for their single-minded devotion to the Bridegroom.

Indeed the Church herself is represented as a woman whose Son crushes the Dragon’s head (Revelation 12:1-6). Men and women together are called to be contending churchmen, sisters of the Elect Lady (2 John 1,13). For this reason, according to the Book of Common Prayer, babies (both male and female) are signed with the Cross with the pledge that they “shall not be ashamed to confess the faith of Christ crucified, and manfully to fight under his banner against sin, the world and the devil” (emphasis added).

The Anglican martyr Hugh Latimer is said to have encouraged his fellow martyr Nicholas Ridley with the words: “Play the man, Master Ridley!” I know this advice goes utterly contrary to the spirit of our age, but I would say to young men and husbands today: “Play the man, gentlemen, in your family and in the Church and world, and in so doing honor your wife and children!” I would also say this to young women and wives: “Play the man, ladies! Don’t disown your manhood! You were created in Adam, just as you are reborn in Christ. Submit to Christ as your Head! Submit to the headship of your husband, even when that requires the patient courage of the martyrs” (such courage means that in situations of death or abuse a widow or a wife may have to play the role of head of household).

Remember, O Man, the Language of Scripture

This essay began as an examination of liturgical language for man and proceeded to examine key texts from the Bible. I have argued that the corporate or representative sense of masculine nouns and pronouns is not an indifferent matter.

In a little treatise on The Language of Canaan and the Grammar of Feminism (1982), Vernard Eller comments on language for the “representative individual”:

“My readers” is an idea totally different from “my reader.” “My readers” are a statistic; “my reader” is a person. The Bible, of course, could not even get its message off the ground without using this representative individual device – largely, I suppose, because of its profound commitment to the “man” anthropology.

He continues by pointing out a second necessary quality of the representative language, its communal dimension:

Undoubtedly the Bible also uses [this device] to underline its own understanding of the nature and importance of community. Often these representational figures are as much challenges to an ideal as they are descriptions of what actually obtains.

Finally, he notes that the Bible’s use of generic masculine pronouns allows it to avoid the distraction of dual genders in order to highlight the corporate, and in this case feminine, character of the Church:

Thus the church is to be feminine in relation to what? To the masculinity of God (or Christ), of course. And the relationship is just as essential the other way around: the masculinity of God has no meaning at all unless there is a femininity toward which it can act “masculinely.”

As a striking example of the corporate feminine, consider this famous hymn:

The church’s one Foundation is Jesus Christ her Lord;

she is His new creation, by water and the Word;

from heav’n He came and sought her to be His holy bride;

with His own blood He bought her, and for her life He died.

Try substituting “it” for “she.” It dies.

So far as I can see, Eller’s arguments were never engaged, even by Evangelicals, who took the pragmatic decision to limit the fight to inclusive language for God. I was in that camp. In retrospect, I think that was a mistake. By surrendering to the designer usage of “he or she,” then “she or he,” then “s/he,” then “they” (sing.), and finally “zhe,” we opened ourselves to the next questions: “How can I relate to a Father God and a male Savior?” and “If grammatical gender is an indifferent matter, what about gender more generally?” All 57 varieties.

Is it possible to revert to usage of yore (“yore” being about fifty years back)? Let me put it this way: does biblical language for man in the image of God matter? If it is a matter of fidelity to God’s Word, then how can we not uphold the faith of our fathers, and their language of worship?

If the language of Scripture and worship is a mirror of the soul, then it is as image-bearers of God in Christ that we find our true selves. If the mark of ashes on the forehead is also a mark of the promised seal of salvation (Revelation 7:3), how can we not welcome the companion words as well? If with the Church we men of dust await the consummation of her vision glorious, if the right Man on our side, the Second Adam to the fight, is Jesus, I can sing to that!

Note: This essay appeared concurrently in Touchstone (July/August 2019) pages 39-44, and Evangelical Review of Theology 43:3 (July 2019) pages 196-204. Used with permission.

2 comments

Dr. Noll, this is the best way that I’ve heard this idea publicly stated probably ever. It often has misogynistic baggage attached, or a bombastic tone, or a sacramental worldview detached from it. I’d like to make two comments.

You wrote, “The Father is not an icon but the primal Source (another sense of kephalē)”. However, in the 1980’s, the erroneous idea was repeatedly put forward that a meaning of kephale was source, as in the source of a river. This served to weaken the plain, if not easily understandable, meaning of this word in Ephesians 5. Kephalē had the archaic (by Paul’s time) meaning of a mouth of a river, and further, I think it was in the plural, although perhaps memory does not serve, and I’m not able to read the Koine myself. So obviously “source” doesn’t help us with that passage, and some mishandlers of the Word used that meaning falsely, which I don’t think you intend to do at all.

My second comment has to do with a wife taking her husband’s name. I think this is a fine practice, but it has not been universally adopted throughout Christendom. My understanding is that in Scandinavia, as well as in Russia, a wife continues to use her father’s name, as in “Kristin Lavransdatter.” This doesn’t automatically interfere with men and women appropriately bearing God’s image in this cultures.

Thank you for writing this article. An excellent example of modern English usage which still respects this idea is Joy Davidman Lewis’ book Smoke On the Mountain. I hope you get some engagement with some Millennials, or some Gen Xers, or even some Baby Boomers, from this. But that last might be too much to hope for.

Marmee March

Thank you for your kind words and comments. To begin with the latter, I am not a linguist or cultural anthropologist. In Uganda, for instance, children normally do not take either father’s or mother’s “family” name. It would be interesting to trace how the “traditional” Western usage evolved and whether it involved a Christian understanding of man.

As for the meaning of kephalē, I am aware of the dispute between egalitarians and complementarians (Thiselton, 1 Corinthians, pp. 800-848). While I think the complementarians have the better case, it is hard to think that kephalē, like archē, does not include the sense of priority or seniority. Clearly my attempt to make a distinction in Paul’s usage of kephalē here reflects the later Arian debates over the “monarchy” of the Father (cf. 1 Cor 8:6).

Comments are closed.