“My God, My God, Why Have Your Forsaken Me?”

Mark 15:34

I preached this meditation on Good Friday 2013 at my parish church in Pennsylvania.

It is reported in two Gospels – Mark and Luke – that Jesus cried out in a loud voice at the end of his life.

According to Mark,

And at the ninth hour Jesus cried with a loud voice, “Eloi, Eloi, lema sabachthani?” which means, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Mark 15:34)

And in Luke it reads:

Then Jesus, calling out with a loud voice, said, “Father, into your hands I commit my spirit!” And having said this he breathed his last. (Luke 23:46)

These are the only two of Jesus’ words from the Cross addressed to the Father on his own behalf. Usually, I think, we see these two words to be very different. The Fourth Word, my text today, is seen as the “cry of abandonment,” a passionate question directed to God much in the manner of Job. The Seventh Word from Luke, it is thought, breathes quiet confidence, with Jesus speaking intimately with the Father.

I do not think these cries are all that different. The Seventh Word is not a resigned murmur between Jesus and the Father. Both words are cries, public proclamations to all who stand by at the Cross. Both words are a kind of prophecy, prophetic prayer addressed to God but overheard by men, like Jeremiah, who openly shared his prayers, his spiritual struggles with God. (e.g., Jer 20:7).

Beyond the prophets, however, the entire Book of Psalms can be seen as prophetic, and in fact both these words from the Cross are taken from the Psalms, in particular Psalm 22 and Psalm 31. The psalms, I have taught my students, are not only the prayer book of David, but the prayer book of Adam, that is, they incorporate the full range of emotions and experience known to humanity. What is fascinating is how often within one psalm, the pray-er moves from sentiments of loneliness and fear to confidence and joy. Both psalms that Jesus prayed from the Cross contain this movement.

The way I see it, our Lord on the Cross did not vacillate in his feelings of fear and hope; rather, his cries from the Cross incorporate the full spectrum of human life – and death. I believe these two cries were part of Jesus’ death throes. Again, the psalms of all the Scriptures speak most directly about the experience of death. Listen to Psalm 88:

O LORD, God of my salvation; I cry out day and night before you…. For my soul is full of troubles, and my life draws near to Sheol. I am counted among those who go down to the pit; I am a man who has no strength, like one set loose among the dead, like the slain that lie in the grave, like those whom you remember no more, for they are cut off from your hand. (Psalm 88:1-5)

The spirit of these verses – the Psalmist’s sense of abandonment, his questioning of God’s purpose, his fear of the unknown realm called Sheol – is summed up in Jesus’ cry: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

Now let me ask you a question. Do you have a soul? Do you believe in the soul? Many materialists today think human beings are mere biological machines, the product of blind evolution, and when the body dies, it’s all over. This is not a new idea, but the vast intuition of human experience, expressed in various religions and philosophy, is that there is a soul, a person, a me inside my physical body that survives death. That survival may be thought happy, frolicking in the fields of Elysium, or sad, flickering in the gloom of the netherworld.

Biblical faith, before Christ, takes the gloomy view of life after death because God created man as a composite of body and soul, and death involves a permanent separation of the body and the soul. So David laments: “O Lord, deliver my soul; save me for the sake of your steadfast love. For in death there is no remembrance of you; in Sheol who will give you praise?” (Psalm 6:4-5).

The Lord Jesus was standing at death’s door and finding it closed, even to His great vision. How many of us can really imagine our own death? We have seen others die and we can speak abstractly about it, but can we really enter into the experience of dying? Perhaps we need to turn to our greatest poets to help us.

Here is Hamlet’s famous “To Be or Not to Be” meditation on suicide:

Who would Fardels [Burdens] bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscovered Country, from whose bourn

No Traveller returns, Puzzles the will,

And makes us rather bear those ills we have,

Than fly to others that we know not of.

And here is Emily Dickinson imagining her death-bed scene:

I heard a Fly buzz — when I died –

The Stillness in the Room

Was like the Stillness in the Air —

Between the Heaves of Storm –

The Eyes around — had wrung them dry —

And Breaths were gathering firm

For that last Onset — when the King

Be witnessed — in the Room –

I willed my Keepsakes — Signed away

What portion of me be

Assignable — and then it was

There interposed a Fly —

With Blue — uncertain stumbling Buzz –

Between the light — and me —

And then the Windows failed — and then

I could not see to see —

Each one of us, whether we are old or young, rich or poor, happy or unhappy, will face that moment when trembling we face the unknown and “commit our Spirit” willingly or unwillingly into the darkness and bequeath our bodies to decay and death. In Jesus’ cries from the Cross, God sympathizes with our human condition – for indeed He has been tested in every way we have.

There is, I think, another dimension of Jesus’ words that goes beyond human experience. Let us remember that Jesus Christ is Very Man and Very God, and the cry “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me!” involves an inner-trinitarian dialogue – God speaking to God, as it were. What can this mean? We enter here into a deep mystery.

In death, we fear what we know to be in some sense natural and inevitable: the separation of body and soul. Man is born to live and die. Our souls have no ownership right to our bodies. Quite the contrary: separation is built into our DNA, an iron law of creation. But Jesus Christ is the incarnate Son of God. When Jesus was born, a new Being came into the world – the God-Man. Just as “Jesus of Nazareth” in a sense did not exist before His conception in the womb of Mary His mother, so also after the Word became flesh, He no longer exists separate from the Name, the Body of Jesus. From Christmas Day on into eternity, there is only the one Lord Jesus Christ, son of David, son of God.

Jesus’ “Why?” directed to the Father confronts the imminent undoing of the Incarnation. As He approaches the door of death, He foresees His soul separated from His Body. But for Him, unlike for us, this is a seeming impossibility. How can the Person of the God-Man be split in two? Some Christians in later ages called Nestorians speculated that the divine and human natures of Christ could be separated. Against them, the Athanasian Creed states:

For the right faith is that we believe and confess that our Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, is God and man… Who, although He is God and man, yet He is not two, but one Christ. One, not by conversion of the Godhead into flesh, but by taking of that manhood into God. One altogether, not by confusion of substance, but by unity of person.

Surely the death of Jesus Christ confronts us with a great mystery. It recalls the most remarkable event of the Old Testament, the Sacrifice of Isaac. When Abraham raises his knife, he is killing the Promise of God, the only Son through whom Israel and the nations will be blessed. Of course, God stays Abraham’s hand. But God does not stay His own hand, He does not spare His own Son Jesus, whose Body soon hangs lifeless on the Cross.

Jesus Himself confronts that mystery when he cries out “Why have you forsaken me?” We know the answer, from the Resurrection side of history. Jesus’ question not only involves a dialogue but a transaction: God dealing with God, for us men and our salvation. The very Person of God’s Son is rent asunder so that we might be joined to Him, partakers of not just His human nature but partakers of the divine nature (2 Peter 1:3). He gave up His Spirit in death, so that we might receive His Spirit and be born again and raised to the life immortal.

Jesus’ cries from the Cross were apparently not heard. He died the dis-incarnate Son and his spirit descended into the half-world of the dead. Is this Jesus’ final word on Good Friday? I think not. There is a third and final cry found in John’s Gospel. It is the one word “Finished!” Like the other words, this one is prophetic. Jesus foresees and proclaims that the transaction – the atoning work of God – is now at the point of completion. His death is once for all and his Resurrection is once for all. Christ being raised from the dead, death has no further dominion over him. “Finished” looks forward to Easter Day, when His Spirit is reunited for evermore with His glorious Body. It looks forward to the proclamation of the Gospel, whereby we who have been united with Him through baptism in a death like His “put on Christ,” confident that we shall be united with Him in a resurrection like His (Rom 6:5).

In these words from the Cross we have plumbed the depths – the depths of death and the depths of love. Jesus’ final cries from the Cross give assurance that God Himself has passed through that awesome door, which shall never again be closed. This is truly comforting and therefore we can join with the Psalmist’s hopeful words found in the Burial Office: “Wherefore my heart is glad, and my glory rejoiceth: my flesh also shall rest in hope… Thou shalt show me the path of life: in thy presence is fulness of joy, and at thy right hand there is pleasure for evermore. (Psalm 16:9-11)

Today’s hymn is John Newton’s “Amazing Grace, How Sweet the Sound”

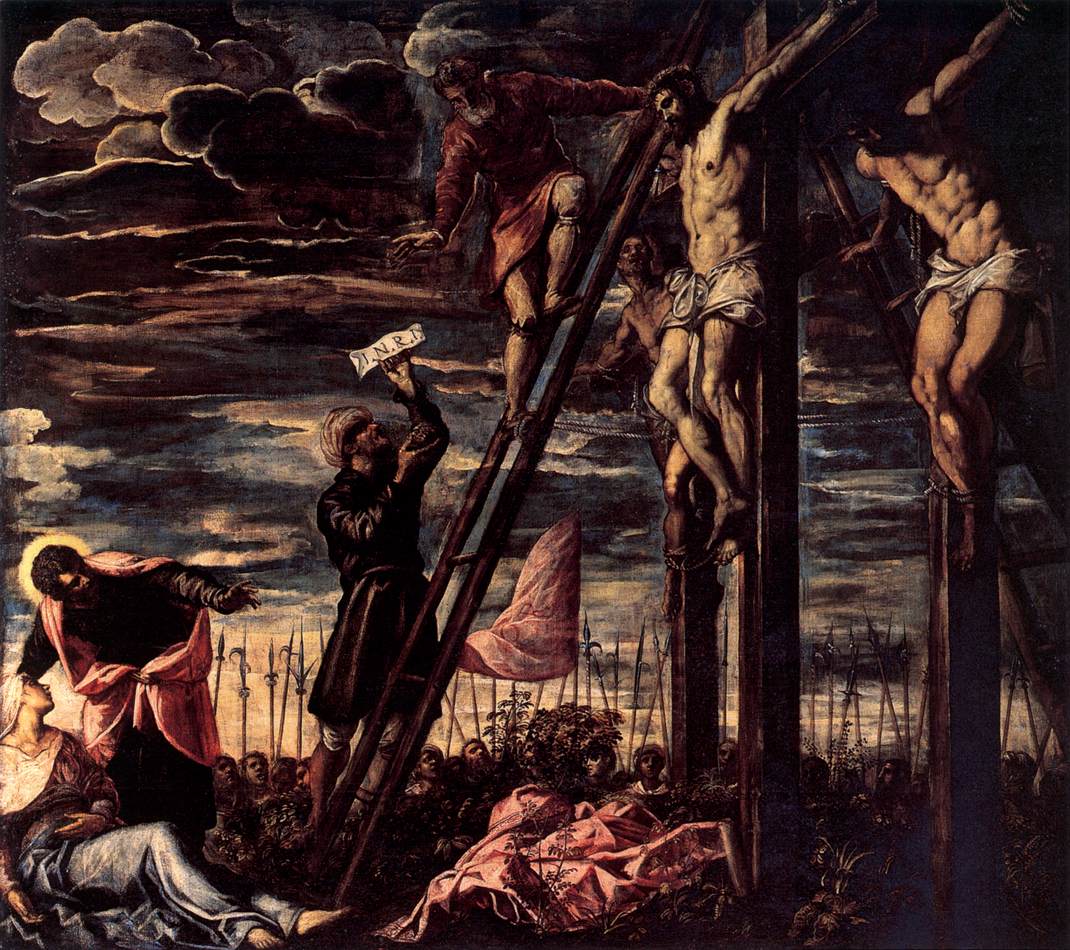

Cover art: Tintoretto, “The Crucifixion” (Wikimedia Commons). Affixing the mocking INRI (“Jesus of Nazareth King of the Jews”) inscription to the Cross.