Note on “Anecdotage”: From time to time I shall include shorter notes or reflections drawn from my threescore years and ten(+).

On April 5, 1967, I was a junior at Cornell University and awoke to the news of a tragic fire at the dorm which housed the “Six-Year Ph.D.” students in which eight students and a faculty advisor died. Rumor had it that a small group had been reading the prophecy of Ezekiel in the basement, where the fire is thought to have started:

“in the fourth month, on the fifth day of the month, as I was among the exiles by the Chebar canal, the heavens were opened, and I saw visions of God… As I looked, behold, a stormy wind came out of the north, and a great cloud, with brightness around it, and fire flashing forth continually, and in the midst of the fire, as it were gleaming metal. (Ezekiel 1:1,4)

One year later, on April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King, Jr. was felled by gunfire, and fires broke out on the Cornell campus and afterward through campuses and cities around the country in the summer of 1968.

The late Sixties was indeed a time of fire and fury. It was a time of student radicalization, and I was a Sixties radical. Just not in the direction many of my peers took.

Let me start, however, with the question of race. I grew up in the (mildly) segregated suburb of Arlington, Virginia. I remember trooping out of my junior high classes onto the playing field in response to bomb threats when the schools were integrated. My Unitarian church was similarly threatened. As a high school student I marched with a “U.U.” (i.e., Unitarian-Universalist”) armband to hear Martin Luther King, Jr. give his famous “I have a dream” speech, with its vision of a nation where people “will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

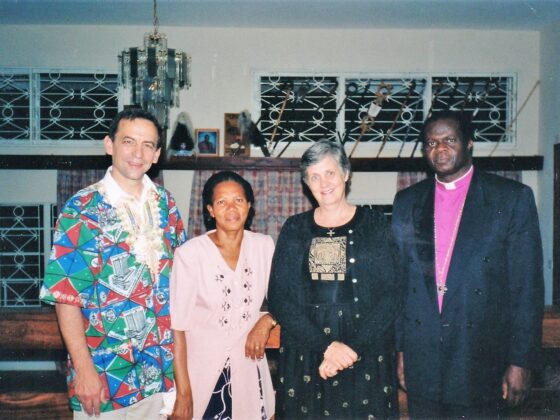

Noll Private Collection

Much has changed with regard to race over the past half century – much good and much not good at all. My core conviction – after living in Africa for ten years and having a diverse-race family myself – remains that race is only skin deep and that culture, in the broadest sense of education and worldview, is far more significant in forming one’s identity. I was interested, for instance, in the latest issue of National Geographic dedicated to the proposition that “There’s No Scientific Basis for Race: It’s a Made-Up Label”.

So race was not the cause of my radicalization. Jesus was. I had left my Unitarian roots behind for a more generic agnosticism before I found myself confronted with the call of Jesus Christ. In the year of the Cornell fire, I read The Cost of Discipleship. “When Christ calls a man, he bids him come forth and die,” wrote Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who a decade later died for his faith. At that point I became a new kind of Sixties radical, a radical Christian.

The fire had descended upon me. Within twelve months, I was baptized, confirmed, and married in the Episcopal Church and set off to seminary – in Berkeley, California!