The following sermons were preached at Redeemer Anglican Church, North Boroughs, PA, as preparation for members of the congregation who were to be baptized, confirmed, and received, as the bishop came on September 19. On this occasion the entire congregation reaffirmed their vows, and in a sense “a new congregation was born!” AN

Basic Believing: Creeds in the Bible

Sermon Preached at Redeemer Anglican Church

June 13, 2021

Third Sunday after Pentecost

LESSONS: Psalm 114: Deuteronomy 26:5-10; 1 Corinthians 15: 1-11; Luke 1:1-4

“So we preach and so you believed.” 1 Corinthians 15:11

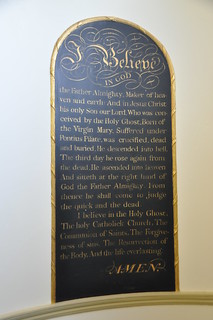

I am beginning a series of sermons today on the Apostles’ Creed with the title “Basic Believing,” because that is the meaning of the word Creed or Credo – “I believe.”

I am going to begin by addressing two negatives, two bad raps on the Creeds. The first objection to the Creeds is that they are about “beliefs,” dead, wooden “doctrines” about God in contrast with the pure spiritual realities of “trusting the Father God,” “walking with Jesus,” “feeling the Spirit moving in your heart.”

Many years ago, I heard a song by a group called the Camerons, titled: “The Holy Ghost will set your feet to dancing.” One stanza went like this:

Now many saints are cold and bound by unbelief today,

They want the blessings of the Lord but worry what men say,

O, let the Lord have full control, from dead traditions part,

And He will set you free within, you’ll have a dancing heart

There is an element of truth in this accusation against creeds. Knowing the Creeds as a set of answers to quiz questions about God is somewhat like knowing about the Ten Commandments and then going out breaking everyone one of them. Similarly, a confirmand can stand before the bishop and recite the Creed with crossed fingers, only to walk about of the building a committed atheist. That’s called hypocrisy, and it is not limited to creeds. I had an employee in Uganda, a member of the Miracle Church, who could pray up a storm at our staff meetings, even as he stole money out of the till. He had a dancing heart all right, along with itchy fingers.

The Creeds are somewhat like the Ten Commandments. They set the boundaries that channel genuine faith and piety, just as the Commandments channel genuine acts of love. They came into existence as various heretics challenged or distorted the biblical Gospel. And most of the ancient heresies are hardy perennials. They may pop up again with different names, but the satanic deception is always the same: not believing that Jesus Christ is the Son of God and that salvation and eternal life are found in His name alone (1 John 5:12).

Years ago, a student wag at Trinity School for Ministry referred to the candles on the Lord’s table as the landing lights on the Holy Spirit’s runway. The Articles of the Creed are something like that. So to those like the Camerons who disparage the Creeds, I say, take them for what they are: landing lights which liberate our spirits to take off in worship the true God and land safely back in reality.

The second objection to the Creeds is that they are not found in the Bible. This objection goes back to the Protestant Reformation and continues today in many free churches. The Reformers discovered the truth and power of the Word in Scripture, and they tossed out many of the traditions of the Roman Catholic Church. Some radicals among them argued that Scripture was not only sufficient for salvation but sufficient for everything. You had to find a text to brush your teeth in the morning. (Okay, I exaggerate.) This mindset led these biblicists to argue that since you could not find the word “Trinity” in the Bible, then the doctrine of the Trinity was to be rejected as some kind of false flag meant to lead believers astray. “Nothing but the Bible,” they said.

The Anglican Reformers phrased the question of Bible and doctrine more carefully. They said: “Holy Scripture contains all things necessary for salvation so that whatsoever is not read therein nor may be proved thereby is not to be required of anyone as an article of the Faith” (Article 6). First of all, they saw the main purpose of the Bible as proclaiming salvation through the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. Other matters, like the best economic system or end of life issues might combine elements of divine revelation and practical reason. Secondly, they spoke of reading and proving a particular article of faith. From this premise, they believed that the doctrine of the Trinity could be demonstrated from various texts of the Bible, even if the word “Trinity” did not appear. In this regard, the Reformers were in agreement with the early church. The Church Fathers who authored the Creeds never doubted that their doctrine could be proved from the Bible.

It is true that the Bible has a power that the Creeds do not. Men and women have been converted reading the Bible alone. The new Anglican Archbishop of Sydney Australia, Kanishka Raffel, grew up a Buddhist from Sri Lanka who came to faith simply picking up the Gospel of John and reading it. The Creeds usually come after conversion to clarify and form the faith of new converts. And this is absolutely necessary. The New Testament and church history is full of converts who have gone astray and led others astray by half-believing the truth and cherry-picking verses of Scripture.

There is an even deeper fallacy in posing the Bible against the Creeds: the Bible itself contains Creeds! The simplest creed in the Old Testament is called the “Shema”: “Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God, the LORD is one” (Deut 6:4). This creed was Jesus’ starting point in teaching about two great Commandments (Mark 12:29).

The Shema teaches about who God is. He is the Great I AM. There is another creed in the Old Testament that speaks about what He does. This creed is embedded in a thanksgiving ritual, in the same way we recite the Creed within the service. (You’ll find it in our first reading today.)

‘A wandering Aramean was my father. And he went down into Egypt and sojourned there, few in number, and there he became a nation, great, mighty, and populous. And the Egyptians treated us harshly and humiliated us and laid on us hard labor. Then we cried to the LORD, the God of our fathers, and the LORD heard our voice and saw our affliction, our toil, and our oppression. And the LORD brought us out of Egypt with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm, with great deeds of terror, with signs and wonders. And he brought us into this place and gave us this land, a land flowing with milk and honey. (Deut 26:5-9)

This Creed is a summary of the mighty acts of God for His people: calling the patriarchs – Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob –the delivering the Israelites from Egypt and bringing them into the Promised Land.

Likewise, the New Testament has short and long creeds concerning Jesus Christ. “Jesus is Lord!” is the briefest confession of who He is. Given the fact that “Lord” (kyrios) is the word used in the Greek Bible to translate the sacred name YHWH, Christians were in effect saying from early on: “Jesus is God.” At the same time, they were not giving up the core monotheistic faith of the Old Testament, but they were moving it in a “Trinitarian” direction. Here is how St. Paul put it:

For although there may be so-called gods in heaven or on earth – as indeed there are many “gods” and many “lords” – yet for us there is one God, the Father, from whom are all things and for whom we exist, and one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom are all things and through whom we exist. (1 Cor 8:5-6)

Paul is not making this up from whole cloth. The cloth of an early creed is already there. When he says this teaching is for us, he means this is the common teaching of all the apostles.

Just as the Old Testament talks about Who God is and What He does, the same is true of the apostolic tradition. Here is St. Paul again (our second reading today):

Now I would remind you, brothers, of the gospel I preached to you, which you received, in which you stand, and by which you are being saved, if you hold fast to the word I preached to you – unless you believed in vain. For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the Scriptures, and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve. Then he appeared to more than five hundred brothers at one time, most of whom are still alive, though some have fallen asleep. Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles. Last of all, as to one untimely born, he appeared also to me…. Whether then it was I or they, so we preach and so you believed. (1 Cor 15:1-8,11)

This passage is one of the clearest statements of the apostles’ creed in the Bible. Let’s notice several things about it. First, Paul calls it the gospel that he preached to them. This gospel is none other than the Good News of salvation, “in which you are being saved.” He goes on to say that the Corinthians “received” it, and receiving is believing, as he makes clear at the end: “so we preach and so you believed.” Paul is not talking about some abstract concept for theologians to ponder but the very heart of the Christian faith itself.

Secondly, Paul describes himself as a kind of middle-man in conveying this Gospel. He says that he delivered to them what he himself had received. The word for “receive” here means “handing over,” and handing over is of something we call tradition. So Gospel and Scripture are not at odds with tradition.

Third, what Paul is handing over is apostolic tradition, i.e., it is eyewitness testimony of those apostles who followed Jesus and witnessed his death and resurrection, many of whom were still alive when Paul writes. Paul of course describes his own encounter with Jesus on the Road to Damascus as a special belated resurrection appearance, but the Risen Lord did not communicate the content of his Gospel to him; rather, Paul received it through the other apostles.

Finally, the content which Paul gives here matches up pretty closely to the middle part of the Creeds:

- Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures,

- he was buried, and

- he was raised on the third day in accordance with the Scriptures,

So in this short passage, we learn the content of what Paul preached and taught. We also can see how he continues to teach them by reminding them. One might say that is exactly what we do when we recite the Creed in the church service. We are reminding ourselves of the truth on which we stand and by which we are saved.

The substance of the creed in Corinthians is expanded in other New Testament writings, where it is referred to as this “deposit” of faith. Here is one example, where Paul briefly summarizes the deposit for Timothy:

He was manifested in the flesh,

vindicated by the Spirit,

seen by angels,

proclaimed among the nations,

believed on in the world,

taken up in glory. (1 Tim 3:16)

Here Paul is passing on a piece of teaching that includes the “incarnation” of Christ, the role of the Holy Spirit, and Great Commission to the nations.

I am about to stop, but I want to make one more observation about the creeds in the Bible. In some churches, people sing the Creed. In fact, if you listen to recordings of the Mass, the Credo is a major section. Personally, I don’t find the particular language of the Creed easy to sing, but there is a connection between the Bible, hymns and creeds. Let’s take “Holy, holy, holy” which we sang two weeks ago on Trinity Sunday. Notice it begins with the Old Testament vision of Isaiah in the temple of the exalted one LORD of hosts. But the threefold repetition of “holy” suggests that this one Lord is more complicated than the mere number one. This one God is in three Persons, as taught by the creed.

Holy, holy, holy!

Lord God Almighty

Early in the morning

Our song shall rise to Thee.

Holy, holy, holy!

Merciful and mighty

God in three persons

Blessed Trinity!

The Holy Trinity is a great mystery awaiting further revelation, and the hymn then explains one reason: human sin.

Holy, holy, holy!

Though the darkness hide thee

Though the eye of sinful man

Thy glory may not see

Only Thou art holy

There is none beside Thee

Perfect in power, in love and purity.

In contrast with human blindness and weakness, God himself is known by his holiness: “perfect in power, in love and purity.” The third verse moves to a cosmic hymn of praise:

Holy, holy, holy!

Lord God Almighty

All thy works shall praise Thy name

In earth and sky and sea.

Holy, holy, holy!

Merciful and mighty

God in three persons

Blessed Trinity!

This final verse recalls the Book of Revelation, where the slain Lamb enters into history, revealing the Triune nature of God, and the entire creation breaks out in a hymn of praise.

This is the same message as that of the Apostles’ Creed and I shall be coming back to the Trinity next week when I begin with “I believe in God the Father, Maker of heaven and earth.”

Brothers and sisters, Creeds are not dead and wooden, unless our hearts are cold and stony. Creeds are not unbiblical, as they are embedded in the Scripture and summarize the “faith once for all delivered to the saints.

So as we spend the next weeks examining the Apostles’ Creed, line by line, let’s ingest its truth with a reverent and thankful heart and be prepared to sing, “Holy, holy, holy.”

God the Father and Creator

Sermon Preached at Redeemer Anglican Church, Bellevue

June 20, 2021

Fourth Sunday after Pentecost (Fathers’ Day)

LESSONS: Psalm 97:1-7; Genesis 1:1-5; Ephesians 3:14-21; Luke 11:1-4,10-13

Last week I introduced the sermon series on the Apostles’ Creed by noting that the Bible itself, Old and New Testaments, contains creeds. In particular, the New Testament contains short creeds that are Trinitarian and that recount in brief the saving life death and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

If we look at the Apostles’ Creed, we shall easily see that it has three sections, devoted to the three Persons of the Trinity. The first is the shortest: “I believe in God the Father Almighty, Creator of heaven and earth.” It is short but it is packed with important meaning. I want to unpack two elements of this short section: who is God the Father, and how did He create the heaven and earth?

What about God the Father? Let me begin with an observation. I’ll bet you have heard more sermons about being a good parent or a good father – especially on Fathers Day – than you have heard about God the Father. Several decades ago, a leader in the charismatic movement wrote a book titled The Forgotten Father – a really good book that! The book itself was soon forgotten, although, when I was looking through the Trinity Seminary library on this subject, The Forgotten Father was the only book there!

There is a reason for this absence, I think: the doctrine of God the Father, like the Trinity itself, is a mystery. John’s Gospel states this plainly at the end of the prologue. Here is my translation: “No one has ever seen God [the Father]; the only-begotten Son, who dwells in the bosom of the Father, it is He who has now made the Father known” (John 1:18).

Later in the Gospel, the disciple Philip says to Jesus, “Show us the Father.” Jesus answers:

Have I been with you so long, and you still do not know me, Philip? Whoever has seen me has seen the Father. How can you say, “Show us the Father?” Do you not believe that I am in the Father and the Father is in me? (John 14:9-10a)

Of course, Jesus is not saying He is the Father nor is He saying that the name Father is mumbo-jumbo, unrelated to human fatherhood. But the passage warns us not to project our own experiences and relationships with our fathers – who may have been wonderful or horrible dads – on God. God the Father of Jesus as revealed in the Scriptures is both like and unlike any human father, and believing in Him has little to do with helpful tips on fathering.

The biblical doctrine of God the Father, like the biblical doctrine of the One God, is totally strange to the world’s religions. Polytheistic religions have father gods, but they tend to be either senile or promiscuous. Worse yet, many father gods have murdered their fathers. Zeus, for instance, overthrew his father Cronos, who himself had castrated his father Uranos. Although Zeus had a wife Hera, he raped a number of goddesses and women and even a man. Among the Canaanites, El was the senile father God, whereas Baal was the promiscuous god of fertility.

Among monotheistic religions, Islam sees Allah as an impersonal monad, beyond any human analogy, and is quite explicit in stating that he is not a father nor does he have a son. Among the Hebrews, God may on occasions be likened to a father, but he is never called “Father” as Jesus does. In one dispute with Jesus, the Jews allude to Jesus’ illegitimacy, arguing: “We were not born of sexual immorality. We have one Father, even God.” Jesus sees through this ruse and answers: “If God were your Father, you would love me, for I came from God and I am here. I came not of my own accord, but he sent me” (John 8:41-42).

We can only understand the Creed’s “I believe in God the Father” in the terms that Jesus set out when he taught his disciples to pray “Our Father in heaven,” which was his unique way of praying to “Abba, Father.” There is no “Father God,” no “Fatherhood of God and Brotherhood of Man” apart from “the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ,” a phrase that occurs in the salutations of most of Paul’s letters. There is no “Father in heaven” who is not the One God of the Old Testament, who identifies himself “I AM.”

The idea of God as essential Being is shared by the Father and the Son in the act of creation. Here is the way, Paul describes it says in the short creed I mentioned last week:

For although there may be so-called gods in heaven or on earth – as indeed there are many “gods” and many “lords” – yet for us there is one God, the Father, from whom are all things and for whom we exist, and one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom are all things and through whom we exist. (1 Cor 8:5-6)

God the Father is the Source – “of all that is,” including us; Jesus Christ is the Mediator “through whom” all things, and we, come into existence.

The Church Fathers went one step further in inferring that the Father as the Source applies not only to the created order but to what is called the “essential Trinity” as well, God in His very Being. From all eternity, the Father has a priority within the Trinity. The Father begets the Son, and the Spirit proceeds from the Father. You can’t reverse the order without talking nonsense. Begetting, that’s what fathers do. If mothers are “birthing persons,” as some today suggest, then fathers are “begetting persons.” But to be more precise, God the Father is the only true Begetter: human fathers pro-create what God has already ordained.

In many cultures, the father is also the bearer of the family name. God the Father is also the name-bearer of the Trinity. This is why the vast majority New Testament references are to “God the Father” or “the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ.” In our Epistle today, Paul prays to “the Father, from whom every household in heaven and earth is named” (Eph 3:14-15). The universe is a divine patriarchy. This is not to say that the Father does not gladly share his “Godhood” with Jesus. Again, Paul describes the Son’s emptying himself on the Cross and then being exalted to God’s right hand and given the “Name that is above all names.” Jesus is God, no doubt about it.

God the Father is called “Almighty,” as Jesus makes clear in the first petition of the Prayer: “Thy Kingdom come.” God as King is a primary image in the Old Testament. Our Psalm today (Psalm 93) begins by acclaiming “the LORD reigneth.” But the divine King is also the supreme Delegator. From eternity He has enthroned His Son as Lord over the whole creation. Jesus is Lord (kyrios), Jesus is Messiah, anointed King, and this explains the second part of Paul’s greetings: “from God the Father and the Lord Jesus Messiah. The Risen Jesus shall reign over all history until the day when all is completed and He has defeated all His enemies including Death and hands the creation back to the Father and God will be all in all (1 Cor 15:28).

Now we come to the second aspect of the God the Father, according to the Creed: He is Creator of heaven and earth. This doctrine takes us back to the first verse of the Bible: “In beginning, God created the heaven and earth.” Again, many ancient religions have myths of the beginnings, but only Judaism, Islam and Christianity claim that God created out of nothing, that is, that God existed “before all worlds.” The Hebrew bara’, translated “create,” is a special word, distinct from the words to “make” or “shape.” God not only shapes the world, the cosmos, but He brings its building materials, its stuff into being, where there was nothing before. There was a time when the world was not.

Most heresies in the early church derived from philosophers and theologians who wanted to defend the sole supremacy of God the Father. The famous heretic Arius claimed that the Son was an exalted god-like but created being. “There was a time when he was not,” he taught. In effect, Arius made Jesus Christ a gigantic angel.

Speaking of angels, while the Apostles’ Creed says God the Father is “creator of heaven and earth,” the Nicene Creed adds “and of all things visible and invisible.” A brief excursus here: the phrase “all things visible and invisible” was changed in the 1979 Episcopal Prayer Book to “all things seen and unseen.” But these are not synonyms: “seen and unseen” suggests that heavenly and earthly things are in the same material order of nature. We just haven’t built a telescope or microscope powerful enough to see them, but someday we will. No, “visible and invisible” means that God has created entities that exist in a radically other realm or dimension. Paraphrasing Shakespeare’s Hamlet, there are more things in heaven and earth than can be discovered by modern science.

This distinction in wording is no minor matter. One of the offenses that certain people take to the Genesis creation account is the fact that God created light on the first day but the sun, moon and stars on the fourth day. The Bible is making an important point here: the fundamental laws of God that underlie all material reality precede it logically, if not temporally. Modern thought and much empirical science works from a philosophy of materialism, that matter is all there is. But truly, this is absurd.

Put philosophically, there has to be a metaphysics undergirding the physics of everything that is seen. There has to be something “prior,” what Dorothy Sayers called “the mind of the maker.” Recently, our family watched a movie titled The Man Who Knew Infinity. It is based on the true life story of a mathematician named Srinivasa Ramanujan, an impoverished Indian in Madras, who was a mathematical genius. He gets an opportunity to study at Cambridge University with a leading mathematician, D.L. Hardy. Hardy, a self-proclaimed atheist, recognizes Ramanujan’s genius, and under his tutelage Ramanujan devises the “partitions formula,” which solved a puzzle which many mathematicians had considered insoluble. At one point, Hardy asks Ramanujan where he gets his insight, and he says: “I get it from my God.” “An equation is nothing unless it expresses the mind of God,” he says. Hardy replies: “I just can’t believe in God, but I believe in you.” Hardy, it turns out, is the close-minded fundamentalist of the two.

The Christian doctrine of creation is not opposed to the discoveries of modern science. It simply says that there is a Wisdom, a Logos, that informs and indwells these discoveries but that is of a different order. The universe may have begun with the Big Bang in the order of time, but the laws of physics and time itself precede the Big Bang, again logically if not temporally.

Genesis goes on: “God said, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness” (Gen 1:26-27). This little sentence reveals a lot about God and a lot about us. Put simply, God “talks to Himself” He creates our species male and female, and he makes us conversationalists too in our mutual intercourse. I had a student at Trinity once, who had converted from Judaism. When I asked her how this had happened, she said it was because of this verse. Nabeel Qureshi, a devout Muslim who converted to Christianity, compares Tahwid, the Islamic doctrine of Allah’s oneness and the Triune God of the Creed this way: “Allah is a monad: he is not inherently relational. Yahweh, on the other hand, is three persons, inherently relational.” Love is therefore the central principle of God. “God is love,” as St. John puts it simply (1 John 4:8). It is out of that selfless love that He created this universe.

The love of the Father is hinted at throughout the Old Testament, but it is Jesus who directs us to the depth of His fatherly love. Our preacher in Lent, talking about the Lord’s Prayer, drew our attention to the scandalous behavior of the prodigal father, who hitched up his robes and ran to meet his returning son. In our Gospel lesson today, Jesus moves rhetorically from the natural generosity of a father in providing food to his children, to the supernatural generosity of the heavenly Father, who gives His Holy Spirit to those who ask him” (Luke 11:13). How much more, St. Paul argues, will this Father “who did not spare his own Son but gave him up for us all … with him graciously give us all things” (Rom 8:32).

Fathers, mothers, sons and daughters, brothers and sisters. As we honor our earthly fathers this day, let us above all be sure to “bless the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who has blessed us in Christ with every spiritual blessing in the heavenly places” (Eph 1:3).

Let us pray:

O heavenly Father, you have filled the world with beauty: Open our eyes to behold your gracious hand in all your works; that, rejoicing in your whole creation, we may learn to serve you with gladness; for the sake of him through whom all things were made, your Son Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

God the Son, True God and True Man

Sermon Preached at Redeemer Anglican Church, Bellevue

June 27, 2021

Fifth Sunday after Pentecost

LESSONS: Psalm 8; Hebrews 2:5-18; Mark 9:1-10

As we continue this series of Catechetical Sermons, let’s move forward from the affirmation of God the Father to God the Son. The Prayer Book version puts it this way:

I believe in God the Father Almighty, Creator of heaven and earth.

I believe in Jesus Christ, His only Son, our Lord.

There is a small discrepancy here: there is no second “I believe” in the original text, which says simply: “I believe in God the Father Almighty, Creator of Heaven and Earth; and in Jesus Christ, His only Son, our Lord.

The Prayer Book is bracketing the distinct Trinitarian Persons: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. While this emphasis is not incorrect, the original Creed is focusing on another matter: the unique nature of Jesus Christ, who is True God and True Man. The early church had to wrestle with two errors concerning the Son of God. One error called docetism claimed the Son only seemed to be human but was really a mask of the one God. The other error was Arianism, which claimed that the Son was a creature of God. Arius famously taught that “there was a time when he was not.”

Arius was half-right. It is true to say that there was a time when Jesus of Nazareth was not, which is any time B.C. Indeed that is precisely what B.C. and A.D. mark: at the turn of the ages, the Son of God became the son of Man, whose DNA came from a young woman of Nazareth. During the first thirty years A.D., the Son of God passed through every phase of human development, from the womb to the manger, from the carpenter’s bench to the Cross.

What the Creed teaches is that Jesus Christ is one with God the Father and Creator before all time, and one with the race of Adam, the Day Six creature of dust. We can only grasp the marvelous Good News of Jesus Christ when we can grasp His possessing both Natures – divine and human – fully, not half-and-half, but all in all. The Person of Jesus Christ is just as great a mystery as the Trinity, and it was just as hotly contested in the Church that produced the Creeds.

So with this creedal truth in mind, let’s look at two Old Testament texts. The first comes from the beginning: “So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them” (Gen 1:27). God proceeds to bless them and give them dominion over all the creatures in earth and sky and sea, that is, of all things visible. But what about things invisible (to us)? The Bible says there is a spirit world. I wrote a book once titled Angels of Light and Powers of Darkness. I believe they are out there, or up there. Do you? And if so, aren’t they exalted above us (and fallen below us) in the hierarchy of heaven?

The Book of Genesis does not raise this question, but Psalm 8 does. Here’s my translation:

O LORD, our Lord, how majestic is your name in all the earth, you who sit enthroned above the heavens… When I look at your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars, which you have set in place, what is man that you are mindful of him, and the son of man that you care for him? See, you have made him a little lower than the angels, yet you have crowned him with glory and honor and have given him dominion over the works of your hands and have put all things under his feet. (verses 1,2-5)

The Psalmist is looking through his telescope at the orderly cosmos, with God enthroned at the top, then the invisible world of the angels, and only then the earth creatures. And what amazes him is that God over-reaches and bypasses the spirit world and the angels to crown mankind. “What is man and the son of man?” he asks. The phrase “son of man” is particularly significant. A “son of man” is by definition “born of woman”; a “son of man” is mortal, he passes away like the flowers of the field (Isa 40:7-8). How can the divine, eternal Father, David asks, share a throne with such a weak and transient creature?

The Old Testament leaves this conundrum unanswered. The New Testament Letter to the Hebrews picks up the matter in light of Jesus. The author of Hebrews begins in much the way John’s Gospel begins with the Word-made-flesh, except in this case it is the Son-made-flesh:

Long ago, [he says], at many times and in many ways, God spoke to our fathers by the prophets, but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son, whom he appointed the heir of all things, through whom also he created the world. He is the radiance of the glory of God and the exact imprint of his nature, and he upholds the universe by the word of his power. (Heb 1:1-3)

The Father created the world through His Son, and the Son is the exact imprint of His glorious nature – the Nicene Creed uses this language “being of one nature – one Being, one Substance – with the Father.” St. Paul puts this same doctrine in other words, saying “Christ is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation (Col 1:15). God can only beget God, and God’s Son is begotten of the Father before all worlds.

But then, how can He also be a mortal “son of Man,” an A.D. man. That is the great mystery. That is the glory of the Incarnation. In our Epistle today, the author of Hebrews reaches back to Psalm 8:

It has been testified somewhere, “What is man, that you are mindful of him, or the son of man, that you care for him? You made him for a little while lower than the angels; you have crowned him with glory and honor, putting everything in subjection under his feet.” (Heb 2:6-7)

The Father has crowned His Son Lord of everything from all eternity. He is the true Image of invisible God. He is the true Man, prophesied in the Psalm. But, Hebrews goes on to note: “At present” – in the “little while” of this age, B.C. and A.D – we do not yet see everything in subjection to him.” What do we see then?

We see him who for a little while was made lower than the angels, namely Jesus, crowned with glory and honor because of the suffering of death, so that by the grace of God he might taste death for everyone. (verse 9)

The decisive event of that little while, the hinge of history, happened on Calvary in 30 AD. There, in the unfathomable love of the Father, He crowned His Son. The crown of thorns which Jesus bore was just that, a crown of victory over sin and death. “It was fitting,” the author continues – “fitting!” – that [the Father], for whom and by whom all things exist, should make the founder of their salvation perfect through suffering in bringing many sons to glory” (verse 10).

The Creed gives the answer to the Psalmist’s question, “What is Man?” and “who is the Son of Man?” And this answer is full of Good News, news of comfort and joy because the “fittingness” of the Incarnation is also the fittingness of the Atonement, planned for all eternity. In his book Why God Became Man, St. Anselm argues the connection of Incarnation and Atonement in this way: the debt of sin is incurred by man alone against God, and God alone can cancel that debt, so only He who is God and Man can offer the perfect sacrifice for our redemption. The truth of the Creed needs to be sung, not merely said, as Charles Wesley knew when he wrote: “Amazing Love, how can it be, that Thou my God, shouldst die for me!”

So far I have been describing the divine Sonship of Christ. But of course, the Creed also speaks of Jesus Christ our Lord, and as I say, Jesus was a real man living in Palestine two thousand years ago. So let’s turn to the Gospels and see what they say about Jesus. In particular, did Jesus know from Christmas morning that He was the divine Son of YHWH, the God of Israel. Reading Christ’s mind is speculative, but I think one can say that like any human being, Jesus “increased in wisdom and stature” (Luke 2:52), including awareness of His Sonship. St. Luke gives a particular moment when the young Jesus, at the time of His Bar Mitzvah, separated Himself from His parents, telling them: “I must be about my Father’s business.” Already at this age, Jesus’ reference to “my Father” sets him apart from any Jew of that day.

More than a decade later, Jesus presented Himself for baptism by John, and the Father’s voice sounded from heaven: “You are my Son; this day I have begotten you.” This was the public announcement of Jesus’ Sonship – not, as some heretics ancient and modern have it, His divine begetting – and the start of His three-year ministry. He was immediately tested by Satan’s “If you are the Son of God…” and refused the bait. While He repeatedly demonstrated his Sonship through teaching and miracle, He refused to use the title “Son of God.” Instead, He referred to Himself as “Son of Man,” mortal man, even as He predicted His Resurrection and Second Coming. “The Son of Man,” he said, “is going to be delivered into the hands of men, and they will kill him. And when he is killed, after three days he will rise” (Mark 9:31).

As His time drew near and He prepared to go to Jerusalem and the Cross, another revelation of His Sonship occurred (our Gospel lesson today).

And after six days Jesus took with him Peter and James and John, and led them up a high mountain by themselves. And he was transfigured before them, and his clothes became radiant, intensely white, as no one on earth could bleach them. And there appeared to them Elijah with Moses, and they were talking with Jesus. (Mark 9:2-4)

The scene on the mountain recalls Moses, the Lawgiver, on Mount Sinai, asking to see God face to face. (He was denied.) Then there was Elijah, who was taken into heaven on a chariot and expected back before the Day of the Lord. (He came girded in camel’s hair and was beheaded.) Moses and Elijah were seen talking to Jesus: He was transfigured in glory; they were not. Their inspired words in the Old Testament point to Jesus, but it is God the Father Himself who speaks the final word: “This is my beloved Son; listen to Him.”

Flabbergasted, Peter wasn’t listening: “Rabbi,” he says, “it is good that we are here. Let us make three shrines, one for you and one for Moses and one for Elijah.” One for the Lawgiver, one for the Prophet, and one for the Rabbi here!” Once the vision ceased, of course, it was only the human Jesus who remained with them and told them not to repeat this vision until He had risen from the dead, which was not hard to do, since they did not know what He meant. But the day of Pentecost soon came when Peter would proclaim:

“This Jesus God raised up, and of that we all are witnesses…. Let all the house of Israel therefore know for certain that God has made him both Lord and Christ, this Jesus whom you crucified” (Acts 2:32, 36).

Brothers and sisters, the Creeds say nothing that is not found in the Bible. It is simply expressed in a concise formula. But the early church did not stop with Creeds alone. One of the earliest hymns is called the “Te Deum,” which is directed to the Triune God. Here is the section of praise to God the Son:

You Christ, are the king of glory,

the eternal Son of the Father.

When you took our flesh to set us free

you humbly chose the Virgin’s womb.

You overcame the sting of death

and opened the kingdom of heaven to all believers.

You are seated at God’s right hand in glory.

We believe that you will come to be our judge.

Come then, Lord [“Maranatha!”] and help your people,

bought with the price of your own blood,

And bring us with your saints

to glory everlasting.

The Creed is all about love, God’s love for us. “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life (John 3:16). Another hymn attributed to Thomas à Kempis a thousand years after the Te Deum sounds the same praise of God the Son. It begins.

O love, how deep, how broad, how high,

how passing thought and fantasy,

that God, the Son of God, should take

our mortal form for mortals’ sake!

It concludes with a Trinitarian doxology:

All glory to our Lord and God

for love so deep, so high, so broad;

the Trinity whom we adore

forever and forevermore.

JESUS CHRIST OUR LORD

These three sermons concentrate on the central section of the Apostles’ Creed about Jesus Christ, His Incarnation, Atoning Death, Resurrection and Ascension, and His Second Coming in glory.

Immanuel: God with Us, Man for Us

Sermon Preached at Redeemer Anglican Church, Bellevue

July 11, 2021

Seventh Sunday after Pentecost

Lessons: Isaiah 7:14; 9:6-7; Romans 5:12-17; Luke 24: 14-20

In my sermon two weeks ago, I mentioned that the Apostles’ Creed begins by directing our eyes toward heaven and eternity, speaking of God the Father and God the Son. But when it speaks of “Jesus Christ our Lord,” it moves directly to a brief summary of the Gospel narrative of His earthly life in the first thirty years of the first century: “conceived by the Holy Spirit and born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate, died and was buried.”

So let’s consider the Virgin Birth. I chose for our text the Old Testament prophecy from Isaiah chapter 7. Here is the context of this prophecy. In the year 732 BC the mighty Assyrian chariots were bearing down on the petty kingdoms of the Ancient Near East. Sensing their impending doom, the kings of Syria and Israel (the ten northern tribes) tried to force King Ahaz of Judah into a defensive alliance. The plan backfired: in desperation Ahaz appealed to the Assyrians for help. This short-term move by Ahaz would bring long-term consequences, as David’s kingdom ultimately became a vassal state of the Near Eastern empires and then was destroyed in 587 BC.

But the greater problem, according to Isaiah, was not political but spiritual. Ahaz’s deal-making revealed his lack of faith in Yahweh, the nation’s God and protector. So Isaiah warns: “If you do not stand firm in your faith, you will not stand at all” (verse 9). The prophet then promises the King “a sign as deep as Sheol (the realm of the dead), or as high as heaven” to assure him to stand fast. Ahaz, with fake modesty protests: “I will not ask, and I will not put the LORD to the test.” All right, God says, I’ll give you the sign myself: “Behold, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and they shall call his name Immanuel [God with us]” (verse 14).

Like many prophecies, this one had a short-term fulfillment: Ahaz did father a son Hezekiah, who trusted God, and Judah survived for nearly a century after Syria and Israel were wiped off the map. But there was a much higher and deeper fulfilment of this promise, pointing to the messianic King, as announced by the prophet in this familiar text:

For to us a child is born, to us a son is given; and the government shall be upon his shoulder, and his name shall be called Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace. Of the increase of his government and of peace there will be no end, on the throne of David and over his kingdom, to establish it and to uphold it with justice and with righteousness from this time forth and forevermore. The zeal of the LORD of hosts will do this. (Isa 9:6-7)

It was this promise which was fulfilled seven centuries later when the angel Gabriel announced to the Virgin Mary that she would conceive and bear a son named Jesus by the Holy Spirit. Let me draw several connections with the original prophecy. First, the Virgin Birth was initiated by God: “The zeal of the Lord of Hosts will do this.” Secondly, the Virgin Birth, or more precisely the virginal conception of Jesus, was a miracle contrary to the laws of nature. Women do not get pregnant without a man naturally, whatever tricks the magicians in our genetic labs are up to nowadays. Mary’s husband-to-be knew this and needed a dream from on high to prevent him for putting her away (Matt 1:20).

Finally, the prophecy signified that Jesus Christ was True Man and True God from the moment of his conception. The name Immanuel, God with us, meant something far deeper than God’s intervention in the natural process of conception, as was the case with Sarah and Hannah (Gen 18:24; 1 Sam 1:20). While it is beyond any science to determine how God begot Jesus, it is nevertheless true that it was God Himself, God the Holy Spirit, who “overshadowed” Mary. For this reason, the early church revered Mary as Theotokos, “the God-bearer.” But the Creed also says the Son of God was “made Man,” and hence it is equally true that the Mother of God was also the “Man-bearer.” As I mentioned last time, Jesus referred to Himself as “Son of man,” which means “mortal man,” born of woman and subject to the inexorable downward drag of death. Isaiah’s prophecy is further fulfilled when Jesus’ body was buried and He descended in spirit to the realm of the dead (1 Pet 3:18).

The messianic line from David was a line of mortals, and Jesus Christ, the Man Born to be King, was in that lineage. But Jesus’ genealogy, according to Luke, stretches all the way through David to Adam (Luke 3:38). Our Epistle reading lands us right back in Eden. St. Paul says:

Therefore, just as sin came into the world through one man, and death through sin, and so death spread to all men because all sinned – for sin indeed was in the world before the law was given, but sin is not counted where there is no law. Yet death reigned from Adam to Moses, even over those whose sinning was not like the transgression of Adam, who was a type of the one who was to come. (Rom 5:12-14)

Paul’s portrait of Adam is pretty grim. It’s not the lordly Adam walking naked in Paradise; it’s Adam, clothed in shame, fallen into the bondage of sin and death, cursed and cast out of Eden. That Adam, Paul says, is the prophetic figure of the true Son of Man. Adam foreshadows the broken and humiliated corpse of the Man hanging on the Cross.

In linking Adam to the Cross, the New Testament writers were not demeaning Christ or God’s good creation of mankind in His image. Just the opposite: Jesus is the true Man, “one who in every respect has been tempted as we are, yet without sin” (Heb 4:15). The early church father Irenaeus developed a view that Christ “recapitulated,” i.e., passed through, every stage of human life in order to redeem every last crumb of our humanity. A contemporary writer describes the Gospel story as “Jesus becoming Jesus.” I might be so bold as to suggest that it was necessary for Jesus to reach the age of mature adulthood in order to bring us to full maturity “in Christ” (Eph 4:13; cf. John 7:6).

There is a final dimension to the Immanuel prophecy. Jesus is God with us, as we shall be in Him. In another passage, St. Paul says,

Thus it is written, “The first man Adam became a living being”; the last Adam became a life-giving spirit. But it is not the spiritual that is first but the natural, and then the spiritual. The first man was from the earth, a man of dust; the second man is from heaven. As was the man of dust, so also are those who are of the dust, and as is the man of heaven, so also are those who are of heaven. Just as we have borne the image of the man of dust, we shall also bear the image of the man of heaven. (1 Cor 15:45-49)

True humanity cannot be understood only from below. Jesus cannot be understood only as a creature of dust, “from the earth, earthy,” as the King James Version has it. The first Adam, even before the Fall, was incomplete, needing a partner; and even partnered, Adam and Eve were incomplete, grasping at knowledge to live a good life. The second Adam fulfilled the divine image by being a man of the Spirit, conceived by the Spirit, baptized in the Spirit, His words being Spirit and Truth, and finally giving back His Spirit on the Cross. And He has promised His Spirit to those who believe in Him and are born again. Our justification by faith in Jesus, which is once for all, is accompanied by sanctification, which takes time, walking in the footsteps of Jesus. By grace we have been made partakers of the divine nature, being conformed to the image of His Son (2 Pet 1:4; Rom 8:29).

So the Creed teaches us that Jesus Christ is Immanuel, God with us. It also teaches us that He is Man for us, and the Man for others, including our unexpected neighbors who are ready and waiting to hear the Gospel. The Nicene Creed, which supplements the Apostles’ Creed, begins the section on Jesus saying “for us men and our salvation he came down from heaven… and became Man.”

The Creed, I repeat, is all about love, God’s love for us through Christ: “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life” (John 3:16). The love shared among the Divine Persons – the Father, the Son, and the Spirit – is all-sufficient, and out of the overflowing abundance of that love, God reached down in Jesus Christ and lived and died for us. Last week I referred to the hymn which begins:

O love, how deep, how broad, how high,

how passing thought and fantasy,

that God, the Son of God, should take

our mortal form for mortals’ sake!

The hymn continues through the mighty acts of Jesus’ life for us:

For us baptized, for us he bore

his holy fast and hungered sore,

for us temptation sharp he knew;

for us the tempter overthrew.

For us he prayed; for us he taught;

for us his daily works he wrought;

by words and signs and actions thus

still seeking not himself, but us.

Before I conclude, I want to mention one other way Jesus Christ continues to be present with us and for us – and that is in the Holy Communion. As Anglicans see it, He is present with us bodily in the Communion. Our view is a middle way between two misunderstandings. We do not believe that Christ’s presence in the elements of bread and wine can be localized and concretized; that view, called transubstantiation, rationalizes the divine mystery of our union with Christ. On the other hand, His presence is not merely symbolic, a kind of mnemonic device; Anglicans reject that view, called memorialism, which is also rationalistic and shortchanges Jesus’ words of institution when he said: “This is my Body and my Blood.” Anglicans, along with many Lutheran and Reformed Christians, believe in the real and spiritual Presence of Christ in the sacrament. The Risen Christ is seated bodily at the right of God, yet by His Spirit and through faith we participate in His Body and Blood (1 Cor 10:16).

In the Eucharist, Christ is not only present with us, He is present for us, and our proper response to this presence is thanksgiving. That is what the word “Eucharist” means: thanksgiving. That is the spirit of our Eucharistic prayer:

We earnestly desire your fatherly goodness mercifully to accept this, our sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving… Take and eat this in remembrance that Christ died for you, and feed on him in your heart by faith, with thanksgiving…. Drink this in remembrance that Christ’s blood was shed for you, and be thankful.

To sum up, the Creeds teach that Jesus Christ is the promised Immanuel – God with us – conceived by the Holy Spirit and born of the Virgin Mary. He is also the true Man given for us on the Cross and present in the sacrament of His Body and Blood. In light of this, let us now in the words of the Prayer Book “draw near with faith and take this Sacrament to our comfort.”

“When I Am Lifted Up…”

Sermon Preached at Redeemer Anglican Church, Bellevue, PA

July 18, 2021

Eighth Sunday After Pentecost

Lessons: Isaiah 52:13-53:1-6; Romans 6:1-11; Luke 24:36-53

I grew up as an unbeliever and only became a Christian and was baptized and confirmed when I was half-way through college. So I have this little doubting Thomas voice etched in my conscience that can comprehend the question “Is it true?” “Is God for real?” By contrast, my wife Peggy was a cradle Christian, Episcopalian in fact. When she was in college, in response to a class lecture, she tried to think as if God didn’t exist; she lasted only a day or two before giving up the experiment. God just had to be there!

The revolution in my thinking was not just about God but about Jesus. In my preteen years, I attended a Unitarian Sunday school (Unitarians, it is quipped, believe in no more than one God). I remember they had us read the earliest Gospel of Mark where Jesus cries, “My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?” and where on Easter morning, the story ends abruptly with the women running away in fear because they had come to the wrong tomb. Then they took us to the latest Gospel of John where the Risen Jesus is walking through walls, telling Thomas to stick his hand in the nail- and spear-holes from the Cross and then levitating out of sight. You see, they said, the early Church perverted the kindly moral teacher of Nazareth into the walking and talking God of the Creeds. (A decade later, when I went to seminary, I learned a gussied-up name for this view. It’s called “the development of Christology.”)

Back to my conversion. When I began to read the whole Bible for myself, I found a very different portrait of Jesus Christ and came to the conclusion that C.S. Lewis was right when he said Jesus either was mad or he was bad or He was God. The Creeds come down squarely on the “God” side of this matter: the Son of God is of one Being with the Father and begotten of the Father from all eternity. Equally, the Creeds say that Jesus Christ our Lord was fully human, conceived by the Holy Spirit and born of the Virgin Mary, and that He suffered and was crucified, dead and buried under Pontius Pilate, the Roman Procurator in Palestine in 30 AD. When He rose from the dead and ascended into heaven, He did so in His human (if glorified) body.

Last week I described Jesus’ incarnation not just as the moment of his virginal conception (true though it is) but as “Jesus Becoming Jesus.” With some fear and trembling (for who can know the mind of the Lord?), I am suggesting that Jesus came to discover and His own identity, mission, and destiny as He lived out His life, and over the course of three years He conveyed this life to His apostles, who in turn passed them on to us in the New Testament. This apostolic Good News about Jesus is summarized in the Creeds and is the only reason on this earth that we have hope for eternal life with God (John 3:16).

Surely the most important influence on the boy Jesus was his immersion in the Scriptures of the Old Testament. By the age of twelve, He was already confounding the Jewish teachers of the Law with His mastery of the Bible. He was already a rabbi, a prodigy. But beyond His comprehensive knowledge of Scripture, Jesus brought an inspired insight that was utterly unique, and this insight is at the heart of the Gospel and of the Creeds. It is found in our reading today from the prophet Isaiah. This insight is a “news flash,” indeed a Good News flash from God.

The Book of Isaiah has sometimes been called “the fifth Gospel” because it is filled with prophecies of Christ. Last week we read from early chapters which speak of the Virgin Birth of a Son whose name Immanuel means “God with us” and whose titles are “Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace” (Isa 7:14; 9:6). This is the classic description of the Messiah, the greater Heir of David’s line: the government of the universe, not just of Israel, will rest on his shoulders. Jewish interpreters took these titles as hyperbole. The Messiah was god-like, but not God Himself.

But Jesus understood the prophecy literally: God Himself was coming in person. In chapter 40, God instructs the nation to bear witness to God’s coming: “Get you up to a high mountain, O Zion, herald of good news … say to the cities of Judah, ‘Behold your God!’” (Isa 40:9). The Good News – and I think Jesus read it this way – is that God the Divine King is coming in Person to save His people and indeed the whole world. This insight is revolutionary, and if false, it is blasphemous: the Messiah and the Great I AM are one and the same.

Jesus noted something else equally radical in this latter section of the book of Isaiah. Embedded in it are four passages describing a figure called “the Servant of the Lord.” Modern scholars call these four texts “Servant Songs” (Isa 42:1–4; 49:1–6; 50:4–7; and 52:13–53:12). When we first meet the Servant in chapter 42, he is identified with the people of Israel, recalling God’s promise to Abraham that in his seed the nations of the world would be blessed (Gen 12:3). Now the Lord repeats this promise to his Servant: “I will make you as a light for the nations, that my salvation may reach to the end of the earth” (Isa 49:6). Why do I think Jesus knew this passage? We can hear in it an echo of Jesus’ Great Commission to go into the world and preach Good News to the nations.

The prophecy is not just about the Great Commission. It’s about the great Commissioner, who speaks as God: “All authority in heaven and earth are given to me,” Jesus says. Isaiah’s vision of the messianic Son of God, born of a Virgin, was confirmed when Jesus was baptized and the Father’s voice from heaven said: “You are my Son: this day I have begotten you.” For most Jews, the title Son suggested the power and majesty of the coming Messiah, the second King David. But Jesus – and only Jesus – turned the title “Son” into “Son of Man,” the second Adam, fallen and born to die, and He alone linked Isaiah’s messianic title “Son” with that of “Servant,” i.e., God’s slave.

That’s not all. Jesus went one step further when He identified the “Servant” with suffering and shame. We see this theme most clearly in the final Servant Song in Isaiah, chapters 52-53, which is our text today. The Song begins with a glorious vision: “Behold, my servant shall act wisely; he shall be high and lifted up” (Isa 52:13). But right alongside this vision of glory comes a vision of, well, ugliness: “he had no form or majesty that we should look at him,” Isaiah says, “no beauty that we should desire him… his appearance had been marred beyond human semblance” (Isa 53:12,14).

This paradox of the Servant’s glory and ugliness comes as an utter surprise to the earthly kings, who confess; “He was despised and rejected by men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief; and as one from whom men hide their faces he was despised, and we esteemed him not” (53:3). “We didn’t get it,” the ancient potentates say. And they were not the only ones. My Unitarian Sunday School teacher didn’t get it. My “death of God” seminary professor didn’t get it. I didn’t get it, but for the grace of God.

The Song then moves to one even more marvelous feature of the Servant’s suffering and grief: it was not for his sins but for ours:

Surely he has borne our griefs and carried our sorrows; yet we esteemed him stricken, smitten by God, and afflicted. But he was wounded for our transgressions; he was crushed for our iniquities; upon him was the chastisement that brought us peace, and with his stripes we are healed. (53:4-5)

Jesus alone saw the Servant’s great work as one of vicarious suffering, of atoning for the sins of others.

Finally, the Song states that this suffering was not accidental, but the very will of God: “All we like sheep have gone astray; we have turned – every one – to his own way; and the LORD has laid on him the iniquity of us all” (verse 6).

Now, friends, let me say this – as one who bears the title “Professor of Biblical Studies”: there is no other passage like Isaiah 53 in the Old Testament. Jews in Jesus’ day and down to the present, refuse to accept its clear meaning. And they are not the only ones: Jesus’ own disciples missed the point. When James and John ask to sit at Christ’s right hand in glory, He rebukes them, saying: “the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many” (Mark 10:45).

I believe that Jesus, and He alone, came to understand this prophecy to be referring to Himself. As Jesus and His disciples journeyed toward Jerusalem for Passover, He predicted that He would be handed over to the chief priests and crucified and on the third day rise – but they did not understand Him (Mark 9:32). Then on Easter evening, three days after His Crucifixion, Jesus appeared at Emmaus and “opened their minds to understand the Scriptures,” saying to them: “Thus it is written, that the Messiah should suffer and on the third day rise from the dead” (Luke 24:45-46). Forty days later, Jesus ascended into heaven, having told them to wait in the city until they were empowered by the Holy Spirit to preach the Gospel to the ends of the earth.

In John’s Gospel, Jesus conflates the crucifixion, resurrection, and ascension into one image of being “lifted up.” He tells Nicodemus:

No one has ascended into heaven except he who descended from heaven, the Son of Man. And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life. (John 3:13-15)

This is a strange yet powerful picture of the vicarious atonement: Jesus, the cursed snake, is lifted up on the Cross for the healing of the people. Again, as He entered Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, Jesus announced the coming world-historical crisis, saying, “Now is the judgment of this world; now will the ruler of this world be cast out. And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all people to myself” (John 12:31-32).

Have you noticed that there are three kinds of cross in Christian churches? In Catholic churches the crucifix depicts the broken body of Jesus; in Protestant churches the empty cross reminds us the empty tomb on Easter morning; and in Eastern Orthodox churches the “Christus Victor” cross show Christ enthroned in glory and conquering the powers of darkness. In the same way, I think the Apostles’ Creed expresses in one extended sentence the single “lifting up” of the Son of God: “suffered under Pontius, Pilate, crucified dead and buried, risen from the dead and ascended to the right hand of God the Father Almighty.”

There is one final implication of the Isaiah passage, which Jesus foresaw. At the end of this song, God vindicates the Servant and extends the benefits of saving work to sinners. He announces:

Out of the anguish of his soul … the righteous one, my servant, will make many to be accounted righteous, and he shall bear their iniquities. Therefore I will divide him a portion with the many, and he shall divide the spoil with the strong, because he poured out his soul to death and was numbered with the transgressors; yet he bore the sin of many, and makes intercession for the transgressors. (verses 11-12)

This is why Isaiah is called the fifth Evangelist, because he preaches the justification of the ungodly through the atoning death of Christ. In our baptism, we are symbolically reenacting the death, resurrection and ascension of Christ. In our Epistle today, Paul says:

Do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death, in order that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life. For if we have been united with him in a death like his, we shall certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his. (Rom 6:3-5)

The difference, of course, is that we are still on this side of the valley of the shadow of death, while the Risen Lord is on the other side. But, Paul asserts, when we believe in Jesus Christ, when we walk by faith, we have the assurance of eternal life with him:

Now if we have died with Christ, we believe that we will also live with him. We know that Christ, being raised from the dead, will never die again; death no longer has dominion over him. For the death he died he died to sin, once for all, but the life he lives he lives to God. So you also must consider yourselves dead to sin and alive to God in Christ Jesus. (Rom 6:8-11)

This is the basic believing we confess as Christians. Are we putting our lives in hands of a badman or a madman? Many in the ancient world thought it immoral and crazy to worship a crucified criminal, the so-called King of the Jews. Many in our world think so too. This is the scandal of the Gospel, as Paul expresses it:

For the word of the cross is folly to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God. For the foolishness of God is wiser than men, and the weakness of God is stronger than men. (1 Cor 1:18,25)

What about you? Are you still a doubting Thomas? Don’t let Thomas’ little voice prevent you from the promise: “Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed” (John 20:29). As those who have been baptized into Christ and who now walk in newness of life, let us join with St. Paul in saying: “Thanks be to God for His expressible gift!” (2 Cor 9:15).

He Shall Come Again in Glory

Sermon Preached at Redeemer Anglican Church, Bellevue

August 8, 2021

Eleventh Sunday after Pentecost

Lessons: Daniel 7:9-14; 1 Corinthians 15:50-58; Mark 13:23-32

After a two-week intermission, I am returning today to the Apostles’ Creed and in particular to the final phrase of the section on Jesus Christ our Lord, which reads: “he will come again to judge the living and the dead.”

This brief phrase is a summary of what theologians called eschatology, or “the last things”: death, judgment, heaven and hell. Let’s begin by admitting that there is much about these last things which is a mystery. The folk singer Iris DeMent puts the matter this way:

Everybody is a-wonderin’ what and where they all came from,

Everybody is a-worryin’ ’bout where

They’re gonna go when the whole thing’s done,

But no one knows for certain and so it’s all the same to me –

I think I’ll just let the mystery be.

While I agree that many of the last things are mysterious, I don’t find that people are a-wonderin’ and a-worryin’ enough about where they’re gonna go when the whole thing’s done. Rather, I think our society is in a state of denial. If “letting the mystery be” means a kind of collective shrug of the shoulders, many are going to wake up some day to profound regret.

As Christians, we may certainly ask the questions “how,” “why,” “when,” “where” about the last things – and I shall be coming back to these – but the fundamental question has to do with “Who” holds the future. That Person is Jesus Christ.

But did this last phrase from the Apostles’ Creed come from Jesus? Yes, it did. He said so repeatedly to His disciples, as is the case in our Gospel text today. In the last days, He says, “they will see the Son of Man coming in clouds with great power and glory.”

So how did Jesus come to know this? These past weeks I have been speaking about “Jesus becoming Jesus,” how as the fully human and incarnate Word, Jesus learned about His identity and mission through the Hebrew Bible, the Old Testament. Earlier I suggested that Jesus learned from the book of Isaiah about His role as the Suffering Servant, who would give His life as a ransom for many.

Our lesson today from the book of Daniel is a second text which I think formed Jesus’ sense of His final coming in glory. Daniel chapter 7 describes a vision of the climax of world history in terms of four empires, increasingly tyrannical and culminating with a supreme Despot who forbids God’s Law, persecutes God’s people, and sets an idol of himself in God’s Temple. This figure is the Antichrist later described in the Book of Revelation as the Satanic beast. Now back to Daniel. At the climax of the vision, God Himself appears as an Ancient of Days – a all-powerful heavenly Patriarch – coming in glory to judge these evil empires. But He is not alone when he appears:

with the clouds of heaven there came one like a son of man, and he came to the Ancient of Days and was presented before him. And to him was given dominion and glory and a kingdom … and his kingdom is one that shall not be destroyed. (verses 13-14)

What is striking about this vision – and I think this is how Jesus understood it – is that the second figure is “a son of man,” that is, he is human, not a spirit or an angel. No, he is born of a woman, he is mortal, subject to the power of death. This vision answers the question posed in Psalm 8: “What is man that you are mindful of him, the son of man that you visit him?” The answer to this question is the One who is both Son of God and Son of Man, Jesus Christ.

There is a second striking question raised in of Daniel’s vision: is this son of man ascending to the throne of the Ancient of Days or descending with Him to judge the earth? Maybe both, like the angels ascending and descending on Jacob’s ladder (Gen 28:12; cf. John 1:51). What Jesus and the Creed are saying is that the mission of God’s Son involved an ongoing movement from heaven to earth and back again, as the song says:

You came from heaven to earth, to show the way

From the earth to the cross, my debt to pay

From the cross to the grave, from the grave to the sky…

And there is a grand finale to this movement: His glorious return to judge the living and the dead.

So now that we know the Who who spoke of His coming again, let’s take a look at the questions: “how?” “why?” “when?” and where?” of the Last Things.

How will Christ return? The Nicene Creed adds the little phrase: He will come in glory. Jesus Christ is the radiance and exact imprint of the Father’s glory, which He possessed before all time (Heb 1:1-4). It is the glory He suppressed when He humbled Himself to be born in a stable in Bethlehem and to live the life of a servant (Phil 2:5-7). It is the glory which flashed forth momentarily on the Mount of Transfiguration. It is the enduring glory He received when He sat down at the right hand of the Father’s throne after the resurrection. And then there is the end. Jesus predicts an astounding explosion of that glory, saying: “Then will appear in heaven the sign of the Son of Man, and then all the tribes of the earth will mourn when they will see the Son of Man coming on the clouds of heaven with power and great glory” (Matt 24:30).

Why will Christ return? He will come again in glory “to judge the living and the dead,” that is, to judge every man and woman living or dead. (This clause, incidentally, upholds the biblical and historic Christian teaching that the human person is both body and soul. The body dies and is buried; the soul lives on in some state until the Day of Judgment.)

The idea of God as judge pervades the Bible. God is good and made all things good, but there is an Enemy who has rebelled against God and tempted mankind into sin. Calling Adam and Eve to account, God judges them with the wages of sin, which is death, from Eden on. In His mercy, God did not leave us dead in our sins and without hope, but He sent His Son to bear the judgment that should have been ours. And now, having raised Him from the dead, the Father has entrusted final judgment to His Son.

What is the basis for this final judgment? In Daniel’s vision, it states “the books were opened”; the same phrase used by John in the Book of Revelation:

And I saw the dead, great and small, standing before the throne, and books were opened. Then another book was opened, which is the book of life. And the dead were judged by what was written in the books, according to what they had done. (Rev 20:12)

Here is how I understand these account books. Those whose names are written in the book of life are the redeemed, those who have put their trust in the Lamb that was slain. Jesus is the way, the truth and the life; no one comes to the Father except through Him (John 14:6). At the same time, no good deed goes unrewarded in God’s eyes, nor is any sin overlooked. It is my view that even for believers there is a purging, a refining of sin, but in a strange sense we shall wish to be cleansed from our impurities (cf. 1 Cor 3:12-13).

What God desires is that believers repent of evil and do good, and that unbelievers repent and come to Christ. The ultimate sin, the sin of Satan, is to know God and refuse Him. So long as a person lives, the door remains open and Christ is knocking and asking to enter his heart. Without repentance, the verdict is sealed in the Second Death, which is separation from God in hell.

This leads to the next question: when will Christ come to judge? The Old Testament prophets speak repeatedly of the Day of the Lord coming at a time of God’s sovereign reckoning. As for the date and time of this coming, Jesus says in today’s Gospel reading: “Concerning that day and hour no one knows, not even the angels of heaven, nor the Son, but the Father only” (Matt 24:36). He goes on to say that the end will come as a complete surprise:

“For as were the days of Noah, so will be the coming of the Son of Man. For as in those days before the flood they were eating and drinking, marrying and giving in marriage, until the day when Noah entered the ark, and they were unaware until the flood came and swept them all away, so will be the coming of the Son of Man.” (verses 37-39)

So stay awake, Jesus says, for you do not know on what day your Lord is coming. (verse 42).

Another way of looking at this question is to say that we should consider the day of the Lord’s coming for us to be the day of our death. If somehow we are alive at that time, our situation before the Judge is no different. When I was a small boy, I somehow learned the prayer:

Now I lay me down to sleep,

I pray the Lord my soul to keep.

If I should die before I wake,

I pray the Lord my soul to take.

I suspect today this prayer is considered too scary for children. In earlier times and even in many parts of the world today, surviving to the next day, especially for children and the poor, is hardly to be assumed. And in any case, each one of us, young or old, has a due date with God. Forgetting this reality is part of what I am calling our collective amnesia. Think of those occupants in the condo collapse in Florida recently. They fell asleep in this world and woke up in another. So, Jesus says, keep awake with God, even as you sleep.

Now to a final question: where does the judgment take place? According to Daniel’s vision, God comes “with the clouds of heaven.” We naturally think of heaven as being “up there,” but only silly literalists were disturbed when Yuri Gagarin, the first man in space, reported back: “I looked and looked and looked and looked, but I did not see God.” Thoughtful Christians have always understood that heaven is a different dimension of reality from the up-down of our material world.

And the same distinction goes for the “where” of our final state. Going to heaven is not a change of location but a change of nature. When we speak of going to heaven when we die, we do not mean floating on clouds playing harps. The new creation, as we see in the final vision of the Book of Revelation, is not fluffy like a Hallmark card but something utterly foreign, a transformation of the good world God created in the beginning into something so marvelous that it can only be described in metaphors.

St. Paul puts it this way in our Epistle today:

Behold! I tell you a mystery. We shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet. For the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised imperishable, and we shall be changed. For this perishable body must put on the imperishable, and this mortal body must put on immortality. (1 Cor 15:51-53)

In The Last Battle, the finale of C.S. Lewis’ Narnia books, the victors find themselves in front of a door. Suddenly the great lion Aslan, the Christ-figure, appears and roars: “Now it is time!” And the door opens. As Aslan stands in the door, all the creatures come streaming toward him. Judgment happens when they enter in at the door (or swerve away from it); but this is just the beginning of the end. “Further up and further in!” is Aslan’s cry to those pilgrims as they climb to higher and higher vistas. And as they do, they begin to meet other residents of Narnia from earlier stories and ages who are being transformed. The Apostles’ Creed returns to this glorious subject in its last phrases about “the communion of saints” and “life everlasting,” and we’ll return to it later too.

So let’s come back to earth here and now. There is perhaps a proper Christian way to “let the mystery of the last things be.” In the next section of the Creed, we encounter the Third Person of the Trinity, who will dwell in our hearts as we await the glorious coming of our Lord Jesus Christ.

Without forgetting the glorious hope of Christ’s Return, we now return to our daily journey of faith, hope and love.

Maranatha! Come, Lord Jesus!

The Holy Spirit, God in Us

Sermon Preached at Redeemer Anglican Church

August 15, 2021

Twelfth Sunday after Pentecost

Lessons: Psalm 51:1-12; Acts 8:4-8,12,14-17; John 3:1-16

The Apostles’ Creed, as we have noted, is Trinitarian in shape and moves swiftly from naming God the Father, creator of heaven and earth and naming Jesus Christ, the Son of God, to the longer central narrative of Jesus’ earthly work: conceived by the Holy Spirit and born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate, crucified, dead and buried, risen on the third day, ascended into heaven to God’s right hand.

Now we come to a third and final section of short phrases, which reads:

I believe in the Holy Spirit, the holy catholic church, the communion of saints, the forgiveness of sins, the resurrection of the body and the life everlasting.

At first glance, this section might seem a grab-bag of miscellaneous doctrines, but at closer look it is held together by the Person of God the Holy Spirit. This section is also, for the first time in the Creed, about us – “us” individually and corporately as the church. So I have titled this sermon: “The Holy Spirit, God in us.”

Of the many mysteries of the Triune God, the identity of the Holy Spirit is especially mysterious. In our mind’s eye, we can imagine God the Father and God the Son, because we all have experience of fathers and sons, and we can definitely imagine the historical Jesus, because he is portrayed at some length in the Gospels. But the Holy Spirit is almost by definition inconceivable. Jesus Himself said of the Spirit: “The wind blows where it wishes, and you hear its sound, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes” (John 3:8). The closest the Bible gets to an image of the Spirit is that of a dove, but we know immediately that this is a metaphor for its movement, not its identity. (One can use “it” or “he” or even occasionally “she” for the Spirit because the Spirit is “neuter” in a way the Father and the Son are not.)

None of this is to say that the Holy Spirit is not a real Person of the Trinity, only that he is hard to visualize. Let me try out an analogy between the divine Spirit and the human soul. Ask this question: “who am I?” Geneticists may chart the human genome; neuroscientists may map the synapses of the nervous system and areas of the brain; computer scientists may design “artificial intelligence” programs that can talk to us and beat world masters in chess, but none of this expert knowledge explains the reality of the soul, that invisible source of our identity as creatures made in the image of God.

With great caution, I would say that the Holy Spirit is something like the soul of the Triune God. The human soul is the source of life, of dynamism, of motivation. So also God is the “living God,” the God of power, and above all, the God of love, and the Holy Spirit is particularly associated with these attributes: life, power and love.