In 2008, Bishop Gene Robinson “married” Mark Andrews, his same-sex partner of 21 years, having previously divorced his wife, the mother of their two children. In 2014, Robinson announced that he and Andrews were divorcing. Neither of these divorces has tarnished his all-star status in the Episcopal Church as an “apostolic pioneer.”

So it should come as no surprise to learn that Bishop Robinson was the preacher at the joint same-sex wedding for 15 couples in the Episcopal Diocese of Dallas in January 2019. “‘Turn around and try to absorb all the love for you in this room, please,’ he told the couples as his voice cracked.” Echoes of Bishop Curry of Canterbury!

What might come as a surprise to some is the fact that the Bishop of Dallas does not believe in same-sex marriage. Bishop George Sumner is one of a group of 8 “Communion Partner” bishops in the Episcopal Church who do not agree with their 93 colleagues that same-sex marriage is fine with God.

The normalization of the LGBT agenda has worked its way through the Episcopal Church over the past quarter-century and is now nearly complete. The Church has now approved “trial rites” for same-sex marriage and deleted “husband and wife” from its marriage canon. At its 2018 General Convention, Resolution B012 neutered the last pockets of conservative resistance by stipulating that any dissenting bishops “shall invite, as necessary, another bishop of this Church to provide pastoral support” for any same-sex couple seeking marriage” (§8).

Compliance by the Communion Partner bishops has been total, with the one exception of Bishop William Love of Albany, whose authority over marriages has been restricted. “Marriage equality” is now the single standard, and same-sex couples seeking God’s blessing on their marriage can find it in any diocese of the Episcopal Church.

What the Communion Partners Bishops Have Said

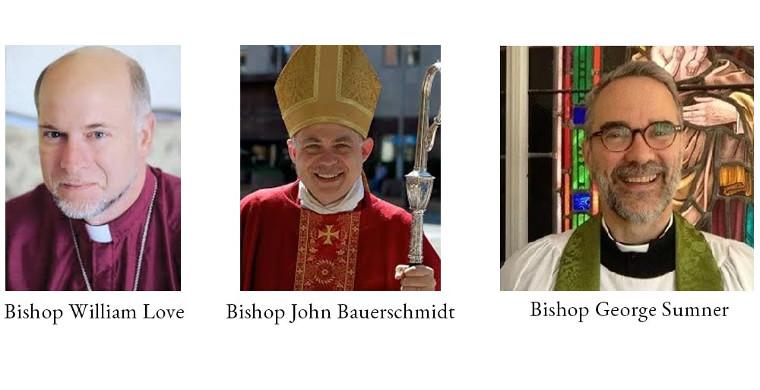

I intend to examine rationales offered by three Communion Partner bishops for their response to Resolution B012. I begin with two complying apologias from John Bauerschmidt, the Bishop of Tennessee (central Tennessee) and George Sumner, Bishop of Dallas (Texas), and I conclude with the one dissenting position of William Love, Bishop of Albany (New York).

Bishop John Bauerschmidt

Bishop Bauerschmidt has invited neighboring Bishop Brian Cole of East Tennessee to assist in providing for same-sex marriages. Bishop Bauerschmidt published a list of “Implementation” procedures. The bishop states that no mission congregation or ministry directly under him may conduct same-sex weddings. He then cedes oversight of “all matters pertaining to marriage,” which would include same-sex or opposite-sex couples, to Bishop Cole. Finally, the document reminds clergy of their vow to obey their Bishop as chief pastor and commends his “Pastoral Teaching on Marriage.”

The body of Bishop Bauerschmidt’s “Pastoral Teaching” document is a comprehensive overview of the Church’s traditional teaching, from Genesis to Jesus’ teaching to Paul in Ephesians and John the Divine in the Apocalypse. The bishop presents this understanding framed by St. Augustine’s “three goods” of marriage: offspring, fidelity, and the sacrament (of Christ and the Church).

So far, so good. The meat of this sandwich comes wrapped in a strange Preface and Conclusion. He opens:

There is no doubt that in our time the Church’s traditional doctrine of marriage is being reappraised. Cultural currents in the societies of the West are flowing in new directions, shaped by new ideas and situations.

Reading this, the lyrics of that horrible hymn “Once to Every Man and Nation” popped into my mind:

New occasions teach new duties,

Time makes ancient good uncouth;

They must upward still and onward

Who would keep abreast of truth.

Bishop Bauerschmidt concedes that “Christian reflection on the wider culture cannot be simply reactive,” because “God is at work everywhere,” “the spirit blows where it wills (Jo 3:8),” and the “influence of the Gospel … is felt more widely than simply within the boundaries of the Church.” He goes on to state the church has its own unique culture and resources for discerning the current moment but then bemoans the fact that it “is increasingly seen as counter-cultural” or as “simply irrelevant.”

The conclusion is as equivocal as the introduction. Bishop Bauerschmidt offers the teaching “in a spirit of charity, to all people of good will.” The document “attempts to speak positively of the things handed down, and not negatively about things now coming into view.” Presumably this positivity explains why the bishop does not mention any of the condemnations of sexual immorality in the Old and New Testaments.

Bishop George Sumner

Bishop Sumner has stated his position in three documents. In an “Update,” he announces Wayne Smith (Bishop of Missouri) as a “visiting bishop” for three parishes that have asked for same-sex rites. According to one report, Bishop Smith will provide “pastoral oversight” to these parishes, while Bishop Sumner “hopes” the parishes will invite him to visit. This differs from Tennessee, where the outside bishop was given authority only in matters of marriage; in effect, the Dallas parishes are now pastorally, if not legally, part of the Diocese of Missouri.

Bishop Sumner explains his acceptance of this situation in a “Word from the Bishop” titled “Together” and more fully in a blog article on “What is ‘Impaired Communion’?” I shall focus on the latter piece.

Unlike Bishop Bauerschmidt, George Sumner does not offer an exposition of the traditional teaching of marriage; however, he was a member of a traditionalist team of scholars who participated in a colloquy on the issue in 2010 that concluded:

In the light of our position in support of traditional Christian marriage articulated above, we believe that the range of legitimate possible pastoral responses, as policy for the Episcopal Church (or for a diocese or parish), is limited. For the individual counselor or parish priest there may be room for some discretion or flexibility, but given that the demand is for same sex marriage, it is difficult to see room for compromise.

Although Bishop Sumner believes in traditional Christian marriage, although he voted against [corrected] Resolution B012 this past year, he now supports the arrangement in terms of “a split decision, of impaired communion,” which, he admits, leads to a conundrum: impaired communion is problematic – “because it is impaired!”

He opens with this ecclesiological premise:

We [Episcopal] bishops remain in full communion with one another, and all Episcopalians enjoy eucharistic fellowship with one another. Whatever our impairment means, we are not saying that it puts us in a position of alienation in our sacramental life. This is our communion.

I call this a premise because he asserts it rather than proving or arguing for it. One corollary of this premise is “we are not in a relation of schism within our denomination, but … in a relationship of disagreement within communion.” It seems the classic term “schism” may apply to denominations (e.g., the ACNA) but “heresy” is replaced by the kinder and gentler “disagreement in communion.”

Bishop Sumner details seven “virtues, assumptions, and imperatives for our in-between state.” I’ll note these briefly, with some comments:

- Danger. Rather than mere pluralism, impaired communion means that one side may win out, because “what we believe matters.”

- Humility. Traditionalists “are not masters of our own destiny.” They would be appreciative of liberality from progressives but cannot compel it.

- Differentiation. “We remain part of one Church, but with complex internal relations that we now strive to order.” The term “differentiation” recalls the distinction between essential truths and “indifferent” matters (adiaphora). Bishop Sumner does not give guidance here on how to differentiate, although he touches on it under “Limits.”

- Complexity. He refers to the tension between being as truthful as possible, as faithful to Scripture as possible, and as little divided as possible. The true complexity, as I see it, derives from the fact one party refuses to hear No for an answer, as the Episcopal Church has done since 1998.

- Hope. Bishop Sumner hopes for a “reconciliation,” which is more than agreeableness but brings a restoration in doctrine, practice and mission. Talk about hope and reconciliation is cheap (cue Neville Chamberlain). The most likely future is that predicted by “Neuhaus’s Law”: “Where orthodoxy is optional, orthodoxy will sooner or later be proscribed.”

- Limits. Bishop Sumner recognizes that there are some limits where a church is no longer recognizable or reformable, and he mentions as limits the name of God, the Lordship of Jesus, and the Bible as God’s Word. The 16th-century Anglican Reformers did not leave the Roman Church because it had denied God or Jesus or the Bible, but because it had distorted the doctrine of salvation and obscured the primacy of Scripture. In our day, the doctrine of male and female in God’s image and of holy matrimony is at stake, and this is the very limit where traditionalists have taken a stand.

- Doctrine and service must go together, so let’s get on with it, he says. My response is that of course, there are many things Christians and other neighbors, religious or not, can do together. But in today’s politicized atmosphere, it is naïve to think we have everything in common except our view of sex. Bishop Bauerschmidt is more perceptive in seeing broader anti-Christian currents that affect every aspect of our current culture.

George Sumner seems to have moved from his position of “no compromise” in 2010 to “impaired communion” today. For many of us who served in the Episcopal Church, the steady erosion of orthodoxy over the past two decades brought us to the hard decision that “broken communion” is the only honest and possible option.

Bishop William Love

Bishop Love proved the exception to the rule among the Communion Partner bishops: he spoke strenuously against Resolution B012 in July 2018 and voted against it. Then in November 2018, he wrote a lengthy Pastoral Letter to his diocese, which concluded with a Pastoral Directive stating that the trial rites authorized by Resolution B012 “shall not be used anywhere in the Diocese of Albany.”

Bishop Love’s defense begins with his ordination vows to guard the faith and to teach and uphold the Scriptures. The Episcopal Church, he says, “in effect is attempting to order me as a Bishop in God’s holy Church, to compromise the ‘faith once for all delivered to the saints’ (Jude 3).” He goes on then to make seven points of his own concerning the Resolution:

- It ignores the authority of Holy Scripture. Quoting Jesus’ teaching on marriage in Mark 10, he argues that a secular court ruling for same-sex marriage “doesn’t mean that God, the Father Almighty, creator of heaven and earth” (BCP 96) has changed His mind or His purpose for marriage as revealed in Holy Scripture, which is the living Word of God.”

- It contradicts the Episcopal Church’s “official teaching” in the Book of Common Prayer, as well as the marriage canons of the Diocese of Albany that recognize this teaching. True, he is correct that there is an anomaly between the current Episcopal Prayer Book and the “trial rites,” but it is a weak reed to lean on, because progressives intend to revise Prayer Book in due time and in the meantime have authorized a workaround.

- and 4. It does “a great disservice and injustice to our gay and lesbian Brothers and Sisters in Christ,” by misleading them to believe that God gives his blessing to same-sex intimacy when in fact He has not and to act in ways Scripture declares to be sinful.

- It contributes to false teaching in the Episcopal Church and “brings God’s judgement and condemnation against [it].” He concludes: “I can’t help but believe that God has removed His blessing from this Church. Unless something changes, The Episcopal Church is going to die.” While statistics of church attendance certainly trend that way, I am convinced that the attitude of the leadership is: “We would rather die than change.” That’s noble if you are dying for the truth but demonic if you are not.

- It forces him to violate his ordination vow to uphold Scripture as the Word of God. Aware that he may be charged with violating his ordination oath of obedience to the Episcopal Church, the bishop appeals to a “first promise” to obey God’s Word, as is stated in Article XX of the Thirty-Nine Articles. Bishop Love predicts that this conflict of authority will “open the floodgates” for other clergy and people to leave the diocese as a matter of conscience.

- “B012 places a major obstacle in my ability as Bishop, to ‘share in the leadership of the Church throughout the world’” [another ordination vow]. Bishop Love was, to my knowledge, the only Communion Partner bishop to attend GAFCON in Jerusalem in 2018, which represents a majority of the Anglicans in the world. The irony is that if deposed as Bishop of Albany, he will forfeit his invitation to the Lambeth Conference in 2020.

Shortly after Bishop Love’s Letter and Directive were issued, Michael Curry, the Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church, issued an announcement which warned Bishop Love that he may be subject to an ecclesiastical trial due to violation of his ordination oath and “conduct unbecoming of a member of the clergy.” Further, Bishop Curry issued a “partial restriction” of Bishop Love’s ministry in carrying out his Pastoral Directive. Any priest or layperson in Albany may now conduct or participate in a same-sex wedding with impunity.

Bishop Love in turn has responded to the Presiding Bishop’s ruling, agreeing to abide by the restriction while appealing the ruling to a church Disciplinary Board. It is hard to imagine he will receive a favorable response. The larger question is whether he will be put up for trial and deposed from office.

What is Communion?

“Impaired communion” characterizes the position of 7 of the 8 Communion Partner bishops. This terminology dovetails well with Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby’s call for “walking together” and “good disagreement” at the upcoming Lambeth Conference in 2020. Hence it should come as no surprise to discover that Bishop Sumner is a member of the Lambeth 2020 Design Team.

Having looked at the apologias of Bishops Bauerschmidt and Sumner, I must confess that I find the term “impaired communion” to be a riddle wrapped in an enigma inside a mystery.

In order to evaluate the concept, it may be necessary to give a preliminary definition of “communion.” Communion (koinonia) is a relational term of the highest import that applies to the Persons of the Holy Trinity and the relationship of Christ to His Church: “The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all” (2 Corinthians 13:14). It is also a practical term defining the “tie that binds” the local congregation and the church universal.

The usual marks of fellowship are said to be common doctrine, discipline and worship (sacraments). While there are various accommodations and compromises among churches on secondary matters, the church throughout its history has held certain matters to be essential to maintain fellowship. These matters include the truth of the Gospel and walking in the commandments of Jesus, who said:

Therefore whoever relaxes one of the least of these commandments and teaches others to do the same will be called least in the kingdom of heaven, but whoever does them and teaches them will be called great in the kingdom of heaven. (Matthew 5:19)

While “love” is the summary of Jesus’ teaching, the apostles identify two principal obstacles to communion which their churches are to “flee”: fornication [Grk. porneia, often translated “sexual immorality”] and idolatry (1 Corinthians 6:18; 10:14). Just as the first three Commandments of the Law condemn idolatry, the Seventh and Tenth Commandments condemn all sexual activity outside marriage, and the prophets draw an explicit connection between false sexuality and false religion (e.g. Hosea 1-3).

These criteria are reflected throughout the New Testament writings. St. Paul, writing early on in his ministry to new Gentile converts, makes clear that fornication is a practice directly contrary to life in the Holy Spirit:

For this is the will of God, your sanctification: that you abstain from unchastity (porneia); that each one of you know how to take a wife for himself in holiness and honor, not in the passion of lust like heathen who do not know God; that no man transgress, and wrong his brother in this matter, because the Lord is an avenger in all these things, as we solemnly forewarned you. (1 Thessalonians 4:3-6)

The Apostle’s basic teaching is that turning from fornication to holy matrimony is one of the prime signs of the Spirit’s work and that “God is the avenger” of those who rebel against this rule. In other words, disobedience in this area can lead a person to forfeit the Kingdom of God (cf. 1 Corinthians 6:9-10; Ephesians 5:1-17).

St. John, the beloved disciple and apostle of love, is in full agreement:

Everyone who goes on ahead and does not abide in the teaching of Christ, does not have God. Whoever abides in the teaching has both the Father and the Son. If anyone comes to you and does not bring this teaching, do not receive him into your house or give him any greeting, for whoever greets him takes part in his wicked works. (2 John 9-11)

To walk in love is to follow the moral commandments, and a chief danger in the apostolic church came from sexual libertines whom St. Jude describes as “ungodly people, who pervert the grace of our God into sensuality and deny our only Master and Lord, Jesus Christ” (Jude 4). So St. John counsels, you must not have table fellowship with them.

Anglicans have defined the Church in terms of the marks of “pure and sound doctrine; the sacraments ministered according to Christ’s holy institution; and the right use of ecclesiastical discipline” (Book of Homilies). The clergy and the bishop in particular vow “with all faithful diligence, to banish and drive away from the Church all erroneous and strange doctrine contrary to God’s Word; and both privately and openly to call upon and encourage others to the same.”

The overturning of this biblical and historical rule is the principal reason why Anglicans worldwide have broken communion with the Episcopal Church and the Anglican Church of Canada. It is the reason why Bishop Love has dissented from the Episcopal Church and from his Communion Partner bishops.

Impaired Communion: Flaws and Consequences

Bishops Bauerschmidt and Sumner – and presumably the other Communion Partners save Bishop Love – claim to uphold the “traditional teaching” of the church with regard to homosexual practice and same-sex marriage, but they justify allowing these practices to be publicly celebrated in their dioceses. In essence, they maintain doctrine without discipline or more accurately discipline restricted to certain clergy and congregations of their dioceses.

These arguments, in my judgment, are fatally flawed. One flaw is the selective use of the Bible, in effect avoiding the “whole counsel of God” (Acts 20:27). This flaw is exposed by Bishop Bauerschmidt’s attempt to “emphasize the positive” of God’s design for marriage without mentioning the negative consequences of those who violate that design. As Paul puts it: “For what partnership has righteousness with lawlessness? Or what fellowship (koinonia) has light with darkness” (2 Corinthians 6:14).

The second flaw is the conflating of visible and formal koinonia and true koinonia in the Spirit. This flaw is exposed by Bishop Sumner’s mere assertion that all Episcopal bishops and Episcopalians are in “full communion” with each other. By claiming this, he shuns “schism” while ignoring “heresy” (which falls out of his vocabulary), and he limits “essentials” to selected broad topics while relegating other parts of the “substance of the faith” to secondary status. Surely he is aware that the same hermeneutic that brought same-sex marriage has led to the denial in the Episcopal Church that Jesus is the only way to the Father. None of these “disagreements,” he thinks, can separate the Communion Partner bishops from communion with their fellows on the Episcopal bench.

In addition to its internal flaws, the compromise these bishops propose simply won’t fly. Here’s why. Suppose one or more of the same-sex newlyweds in Dallas belong to or move to a traditional parish in the diocese. Suppose the priest of that parish sincerely believes that this couple is setting a public example of a sinful lifestyle and refuses to serve them Communion in accord with the “disciplinary rubrics” of the Book of Common Prayer (page 409). Surely that priest will be brought up on charges similar to those threatening Bishop Love. Or suppose one same-sex partner presents himself as candidate for vestry or for ordination. On what grounds could the Vestry or the Commission on Ministry refuse him? He is after all a member in good standing of the Episcopal Church and protected by national canons on non-discrimination with regard to sexual orientation and gender identity (Canon III.i.2).

If the bishop himself can change his mind and compromise on this matter, how much more will this affect the clergy under him? How long before a priest will awaken one morning and sense he should begin to perform same-sex weddings – especially when pressed by parishioners or a lobby? How long before a parish calls a rector who fudges or hides his views on the subject? Honestly, can anyone imagine that within twenty years every bishop and every diocese will not make same-sex marriage mandatory. If we learned anything from the past twenty years of conflict, it is that the Episcopal Church progresses in only one direction – Westward.

When all is said and done, why don’t the Communion Partner bishops simply agree to officiate the same-sex services themselves. Since their position does not cause any break in communion with their fellow bishops, why should they not make a public example by explaining the traditional teaching beforehand and then performing the wedding for those who persist. Wouldn’t that be far better than letting Gene Robinson parachute in? Compromised though they may feel, wouldn’t this be a cross they could bear? Wouldn’t it allow them to maintain oversight in their diocese?

The real problem is that this kind of “impaired communion” is a chimera. A house divided against itself cannot stand, and we are witnessing the final collapse of the orthodox witness in the Episcopal Church. The Communion Partners may cede their authority for church discipline, but the powers that be in the Episcopal Church certainly will not be equally gracious to hold-outs. Bishop Love has found that out. He has also discovered that he no longer has any partners. To my knowledge, none of the other Communion Partners has come to Bishop Love’s defense, but even if they were to, what could they do but wring their hands and beg for clemency on his behalf?

Conclusion

Is there a legitimate place for “impaired communion”? Perhaps so. Clearly there are historic differences that have separated Christian churches that may result in separate restrictions on sacraments and church membership. The term “impaired communion” was employed by the Eames Commission with regard to women’s ordination, and that continues to be an area of deep division within the Anglican Church in North America and the wider Gafcon movement. Some for and against women’s ordination regard it as an essential matter of church order, while others see it as secondary. It is hard to see it as a “salvation” issue from which a person may be excluded from the Kingdom of God as is the case with the endorsement and practice of fornication. Further, both sides of the question among the orthodox are committed to search the Scriptures and pray until a clear resolution is arrived at. This cannot be said of the disarray in the Episcopal Church and the official Anglican Communion over matters of human sexuality.

Let me conclude with this personal note. I served as a priest in the Episcopal Church for 37 years and was engaged in the early debates over sexuality there and later in the wider Anglican Communion (see Essay 4 of my book “Communing in Christ” and Essay 5 “The Decline and Fall (and Rising Again) of the Anglican Communion”). Several of the Communion Partner leaders were colleagues in the battle, and I have refrained from critiquing their choice to remain and fight. But it seems to me now that their position has become incoherent and harmful to a conscientious bishop like William Love. It is also a threat to the wider Anglican Communion, as Archbishop Welby pitches his version of impaired communion – “good disagreement” – to the global church.