Twenty years ago, I gave a lecture titled “Seeing Jesus: Who Did Jesus Think He Was?” Here is the way I began it (updated a bit):

When I became a Christian in college, I remember the excitement of opening the Bible for the first time as a believer and reading it to find out about this mysterious stranger who had reached out to me in love. Before I knew it, I was in seminary and learning the dogmas of “higher criticism” of the Bible and the “backward development of Christology.” The two theories interlock: by picking apart the Bible, one can reconstruct a “historical Jesus” for our time. You know, Jesus Christ Superstar!

According to the backward development theory, we begin deconstructing the “high” Nicene Christology of John’s Gospel, where the Word was in the beginning with God and the Word was God and the Word became flesh in Jesus Christ. The Jesus of John’s Gospel can say quite explicitly: “Father, glorify thou me in thy own presence with the glory which I had with thee before the world was made” (John 17:5). But John’s Jesus, so the theory goes, is a very late, and maybe even idiosyncratic, product of the Church’s preaching and reflection. Moving backward in time, we next come to Matthew and Luke, where He becomes Son only at His birth. But even these Gospels are fantasies of the early church. From there we continue back to Mark’s Gospel where Jesus is acknowledged Son only at His baptism. But even here… you get the picture.

The backward development of Christology was standard-issue dogma in mainline seminaries twenty years ago, inspiring the so-called Jesus Seminar, whose “fellows” voted to grant eleven authentic sayings to the historical Jesus and claimed:

Jesus of Nazareth did not refer to himself as the Messiah, nor did he claim to be a divine being who descended to earth from heaven in order to die as a sacrifice for the sins of the world. These are claims that some people in the early church made about Jesus, not claims he made about himself.

Thank God, a new perspective on the Gospels has begun to emerge, even in the academy, that has called into question these dogmas. Scholars like Kenneth Bailey, N.T. Wright, and Richard Bauckham have turned the skepticism of the Jesus Seminar on its head and attributed to the Gospels – both the Synoptics and John – a new status as eyewitness testimony. There has also been a trend away from “historical-critical” to “theological” readings of the Bible, with a new respect for the Church’s canon and interpretation down the centuries.

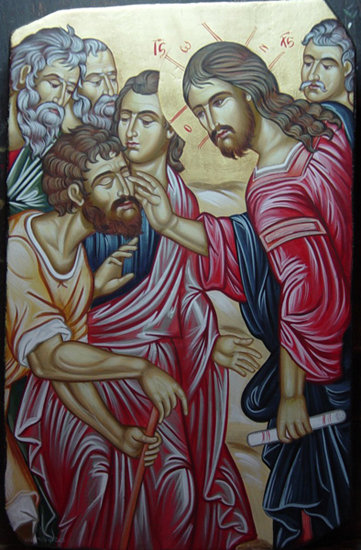

With biblical eyesight restored, we may now see Jesus as Son of God and Son of Man. It is in this context that I wish to commend two recent books.

The first book is titled The Jesus We Missed: The Surprising Truth About the Humanity of Christ (2012), by Father Patrick Henry Reardon. Father Reardon, a former Anglican colleague and now an Orthodox priest, has produced a portrait of Jesus which Russell Moore calls “the best treatment of the humanity of Jesus I’ve ever encountered.” One doesn’t expect an Orthodox scholar to be focusing on Jesus as Very Man, but Father Reardon states the following foundational premise:

An adequate Christology, then, should affirm [that] the Word’s becoming flesh refers to more than the single instant of his becoming present in the Virgin’s womb. He continued becoming flesh and dwelling among us, in the sense that his assumed body and soul developed through the complex experiences of a particular human life, including from preconscious to conscious.

The Jesus We Missed devotes considerable space to Jesus’ early years, based on the author’s conviction that “the foundations of a person’s character are laid in youth.” From his father, Jesus learned manual dexterity and business sense; from his mother he absorbed the spirituality which says, “Be it unto me according to Thy word.” Add to these the powerful influence of the Scriptures themselves, in which he found himself text by text.

This book is written for laypeople yet includes continuous insights for more advanced readers. I found particularly touching the meditation on the Agony in the Garden, where the author intertwines the Synoptic accounts with the Epistle to the Hebrews. Father Reardon does not mince words about Jesus’ emotions of fear and weakness in “tasting death” for our sake: “The thought of death is man’s companion throughout life. It was this fear of death that Jesus faced in prayer.” Passing through this experience, Jesus was inwardly changed and emerged from the Garden empowered to do the Father’s will on Good Friday, enduring the Cross and despising the shame (Hebrews 12:2).

The second book is titled: Jesus Becoming Jesus: A Theological Interpretation of the Synoptic Gospels (2018), by Thomas G. Weinandy. Father Weinandy is a distinguished Roman Catholic theologian, whose book The Father’s Spirit of Sonship (2011) is a widely respected study of the doctrine of the Trinity. Like Patrick Reardon, Father Weinandy brings his theological perspective to bear on Jesus as portrayed in the Synoptic Gospels. Weinandy disowns any claim to expertise in historical-critical method but sees this lack as an advantage in looking at Jesus afresh. And he is right: his commentary is deeply perceptive, reminding me of the brilliant commentaries on Matthew and John by F. Dale Bruner. (note: like Bruner’s books, Weinandy’s is a rich but slow read).

In his exposition of the Annunciation in Luke, Weinandy interprets the event in terms of the divine Persons of the Trinity:

As the Father fathers his Son as man through the action of the Holy Spirit, so the Father eternally fathers his Son through the Holy Spirit [emphasis added]. Only when one perceives this Trinitarian metaphysics does one apprehend, in faith, the fullness of what has been revealed.

In other words, the “economic” begetting of the Son in the womb of the Virgin Mary is a refracted image of the eternal begetting of the Son from the Father.

For Weinandy, the events in the Gospels are “causal acts” of the divine Persons, in particular in the incarnation of the Son.

In his conception, Jesus is, literally, Jesus (YHWH-Saves) in embryo… The son of Mary is prophetically named “Jesus,” but at his naming the prophecy that lies within his name is not fulfilled… The bestowal of the name “Jesus” prophetically decrees what Jesus must do for him to be truly Jesus.

The same Trinitarian dynamic recurs in the latter’s commentary on Gethsemane:

In accepting his Father’s will, Jesus is conclusively and resolutely avowing, “I will be Jesus” and in so doing actually does definitively become Jesus. Having fully configured himself into Jesus, having enacted his name within his agony by conforming his will to his Father’s saving will, Jesus is now able to enact those acts that will obtain mankind’s salvation – his passion and death.

I do not take Weinandy to be teaching some sort of “process theology,” whereby God discovers himself, or an “adoptionist” Christology, whereby Jesus is apotheosized to the Father’s right hand; rather, the author is being true to the Gospels’ portrayal of Jesus as God emptying himself and entering our mode of living in time. Fathers Reardon and Weinandy agree here, I think.

I find it interesting – and spiritually challenging – that as biblical scholarship has opened the door once more to seeing Jesus not as “gentle Jesus, meek and mild” or a preincarnation of Gandhi, but rather as Very God, the conquering Lamb of John’s vision, so it has also opened a perspective on Jesus as “Very Man,” the Servant-Messiah. The Cappadocian Father Gregory Nazianzen states it this way: “What he was [as God], he continued to be; what he was not, he assumed… He was born for a cause – namely that you might be saved.”

May we who, like the blind man Jesus touched and saw trees walking, look again to “see him who for a little while was made lower than the angels, namely Jesus, crowned with glory and honor because of the suffering of death, so that by the grace of God he might taste death for everyone” (Hebrews 2:9; Mark 8:23-25).