Sermon Preached at Redeemer Anglican Church, Bellevue

September 12, 2021 – Sixteenth Sunday After Pentecost

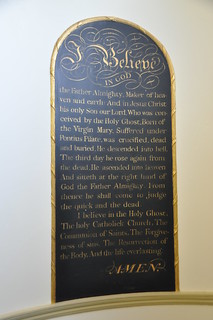

So this is the final sermon on the Apostles’ Creed. We’ve reached the end. And I must make a confession: I’ve enjoyed it! Truth be told, I, like a lot of people, repeat the Apostles’ Creed from memory week by week – that is your assignment for the service next week – without thinking much about it. However, preaching through the Creed set me to thinking and passing it on to you. That’s the price you get for employing a professor as your pastor!

Looking back now after ten weeks, I can see two things about the Creed that I had not noticed before. The first thing is that it has a cross-shaped, a cruciform, movement. Most obviously it moves on a horizontal axis from the beginning, with God the Creator, to the end, with the resurrection of the dead and life everlasting. But it also has a vertical axis, reaching from heaven to earth, beginning with the God Himself, God the Father and God the Son, then the coming down of our Lord Jesus Christ to earth, conceived of the Holy Spirit and born of the Virgin Mary, Jesus of Nazareth, who suffered under Pontius Pilate, crucified, dead and buried down to the depths of the underworld, from which He ascended into heaven, where He now sits enthroned at the Father’s right hand. This exalted Jesus has now sent His Spirit down the same axis into the world and into our hearts, God in us. And the Spirit’s coming has not only been vertical but horizontal, spreading through the mission of the one catholic and apostolic church to the ends of the earth and to the end of time when God will judge the living and the dead. Sorry for the long sentence, but the Creed itself is a long sentence following the first “I believe.”

The second thing I have seen is how biblical the Creed is, even though it never literally quotes the Bible. It unites the beginning in the Book of Genesis with the end, in the Book of Revelation. It touches on the great Old Testament mysteries of the Suffering Servant and the Son of Man and the New Testament mysteries of the God made Man and of the Church, His Body and His Bride.

So with these remarks as a preface, let’s turn to the final phrase in the third section of the Creed, “the resurrection of the dead and the life everlasting.” You may remember last time I spoke, I asked why the “forgiveness of sins” appears in this section rather than earlier when it speaks about Christ dying on the Cross for our salvation, and my answer was that the third section is about God-in-us, in how Christ’s saving work is appropriated and completed in us. Forgiveness of sin is received through the gate of baptism, which we celebrate today. So what about the “last things,” when Jesus comes again in glory to judge the living and the dead?

First, a little Old Testament background. From the book of Genesis on, when God breathes the breath of life into Adam, it is clear that human nature has two elements, body and soul, which are united in our earthly life. It is equally clear that body and soul are separated at death, and the body decays and returns to the dust, from which it came. But what about the soul?

Many ancient peoples believed that at death the soul descended to an underworld, a realm often called Hades. The Hebrew Bible calls this realm Sheol. Sheol was not a fiery hell but a kind of shadow world, and the soul in Sheol lived a kind of half-life, without the light of the eyes and the pleasures of the flesh. Above all, Sheol involved separation from God’s presence, such that David frequently cries out, as in the psalm today: “Do not abandon my soul to Sheol.”

Nobody, almost nobody, could escape death and the trip to Sheol. I say almost, because ancient peoples had a few exceptions, and the exceptions were kings or heroes, in Egypt, the Pharaohs, in Greece, Herakles (Hercules), in Rome the Emperor. These humans were divinized and elevated into the heavens rather than down to Hades. Among the Hebrews, a few spiritual giants like Enoch, Moses, and Elijah, were thought to have bypassed death and Sheol.

What is remarkable then is that the Creed, which follows the New Testament account, states that Jesus was not one of these heroes, rather that He died, was buried, and descended to Sheol. This is the same Jesus, who was found speaking with Moses and Elijah on the Mount of Transfiguration right before His Crucifixion. When Jesus died, His body decayed in the tomb for three days. He was dead and gone. His soul descended to Hades. Wherever we go, He went. So when the Creed goes on to say, that He rose again, it means the whole Man, body, soul and spirit, everything that makes us human, and then some, that “some” being God’s glory, because the Jesus who appeared on Easter morning was true Man raised exponentially to the nth degree.

Now, what about us? In the Old Testament times, the Hebrew people were unsure about resurrection. In a moment of hope, David says: “you will not let your holy one see corruption”; Job likewise in a shaft of light, cries out: “I know that my Redeemer lives, and that in my flesh I shall see God.” In the time of Jesus, one group of Jews, the Pharisees believed in the resurrection of the dead, and another group, the Sadducees, denied it. In our Gospel lesson today, we see that Martha believes that at the last day, Lazarus will rise from the dead. But what Martha does not see is the connection between Lazarus’ resurrection and Jesus. She sees Jesus as a miracle-worker, and indeed Jesus does bring Lazarus back from the dead (only to die again), but more importantly she comes to see Jesus as the I AM of the Creator God, who says to her.

“Martha…. I am the resurrection and the life. Whoever believes in me, though he die, yet shall he live, and everyone who lives and believes in me shall never die. Do you believe this?” She said to him, “Yes, Lord; I believe that you are the Christ, the Son of God, who is coming into the world.” (John 11:25-27)

Oh, friends, this is the sweetest sound our ears will ever hear and our hearts believe. We too say: “Yes, Lord, Yes, Lord, Yes, yes, Lord; Yes, Lord, Yes, Lord, Yes, yes, Lord; Yes, Lord, Yes, Lord, Yes, yes, Lord. Amen.”

The connection between Jesus’ Resurrection and ours is essential to our faith and our future. But getting it right is not always obvious, and this was true from the early church on. If King David and Martha of Bethany had only a distant hope of resurrection, Paul’s converts in Corinth had the opposite problem. They took Paul’s preaching of salvation and the coming of the Holy Spirit to mean that the resurrection had already arrived, and they were walking around as Spirit-filled gods! I have seen this kind of attitude in some “miracle” churches today where pastors teach and people believe that whatever they ask of God, He will give them, from healing of every disease to a gold-plated Mercedes, delivered by a divine Carvana to the door. Sad to say, many of these churches are in the developing world where people struggle with the basic necessities of life.

Paul’s reply to the Corinthian hyper-zealousness comes when he discusses the resurrection and eternal in 1 Corinthians 15. Let me begin by noting that my wife has asked that this entire chapter be read at her funeral. This is St. Paul at full strength.

In the first section of the chapter, Paul recounts the evidence of Easter: the Risen Jesus, he says, appeared to Peter, then to the twelve apostles – Paul doesn’t even mention the women at the tomb, shame on him! – then to more than five hundred disciples at one time, most of whom, Paul notes, are still alive, then to James his brother, then to all the apostles and, last of all, Paul relates, “to me, as to one untimely born.” “So we preached,” Paul concludes, “and so you believed.”

All this is great stuff (Amen?). In the next section (our text today), we find Paul the logician, moving from the sure evidence of Jesus’ Resurrection to disputing the fantastical idea that there is no need for a final resurrection because the end-time has already arrived. He argues:

Now if Christ is proclaimed as raised from the dead, how can some of you say that there is no [further] resurrection of the dead? But if there is no [further] resurrection of the dead, then not even Christ has been raised. And if Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is in vain and your faith is in vain. (vv. 12-14)

At first glance, Paul’s logic may seem a bit obscure. Let me paraphrase it this way. If Jesus was resuscitated to this life only as a kind of zombie, then His bodily resurrection was fake and the witnesses to it, including Paul, are deluded or lying – worse, they are blaspheming God. And if Paul has been lying, then, he says, the Good News of the forgiveness of sins is also a delusion – “and you are still in your sinful body.” And if you are still in your sinful body, then the death of that body will be all there is: end of story and end of History, no final act, no consummation, just one Death and it’s all over.

The poet John Updike presents Paul’s argument this way about Jesus’ Resurrection:

Make no mistake: if he rose at all

It was as His body;

If the cells’ dissolution did not reverse, the molecules reknit,

The amino acids rekindle,

The Church will fall.

Perhaps the poet is tip-toeing too close to the Corinthian fallacy in speaking of cells, molecules and amino acids reanimating, but his main point stands: either Jesus Christ rose bodily from the dead, or our faith is in vain. And if the Gospel narrative is true, it dwarfs every other narrative that people live by.

Paul now wraps up his case with a “but…” and it is this “but…” on which our hope stands or falls:

But in fact Christ has been raised from the dead, the first-fruits of those who have fallen asleep. For as by a man came death, by a man has come also the resurrection of the dead. For as in Adam all die, so also in Christ shall all be made alive. (vv. 20-22)

The Corinthians’ error came in wanting to skip one crucial step in the narrative: resurrection comes after death of the body. They wanted to hop a ride on Christ’s risen life without going through His death. They wanted to become second Adams without dying as the first Adam did. They wanted the reward of the divine life and power without the cost of the divine suffering and death.

Paul corrects them by the using image of a harvest: the farmer has to drop the seed into the furrow, cover it over like a corpose, and wait for the new crop to spring up. The seed is this body of death; the harvest is the resurrection body and the defeat of death.

But [Paul says], each in his own order: Christ the first-fruits, then at his coming those who belong to Christ. Then comes the end, when he delivers the kingdom to God the Father after destroying every rule and every authority and power. For he must reign until he has put all his enemies under his feet. The last enemy to be destroyed is death. (vv. 23-27)

Paul goes on to explain to the walking gods in Corinth that the resurrection body will only be born when the corruptible body dies, and the resurrection body will be infinitely superior to this poor sack we carry to the grave.

This news may sound sombre on one level, but in fact Paul, who has journeyed so far and endured such hardships, breaks forth in a shout of sheer joy: “Death is swallowed up in victory. O death, where is your victory? O death, where is your sting?” As the poet John Donne put it memorably: “One short sleep past, we wake eternally And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.”

Paul concludes this great chapter with a prayer of thanksgiving and a word of advice:

But thanks be to God, who gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ! Therefore, my beloved brothers, be steadfast, immovable, always abounding in the work of the Lord, knowing that in the Lord your labor is not in vain.

This attitude toward death and life is, I think, captured in our final hymn today, “In Christ alone”:

No guilt in life, no fear in death,

This is the power of Christ in me;

From life’s first cry to final breath,

Jesus commands my destiny.

No power of hell, no scheme of man,

Can ever pluck me from His hand:

Till He returns or calls me home,

Here in the power of Christ I’ll stand.

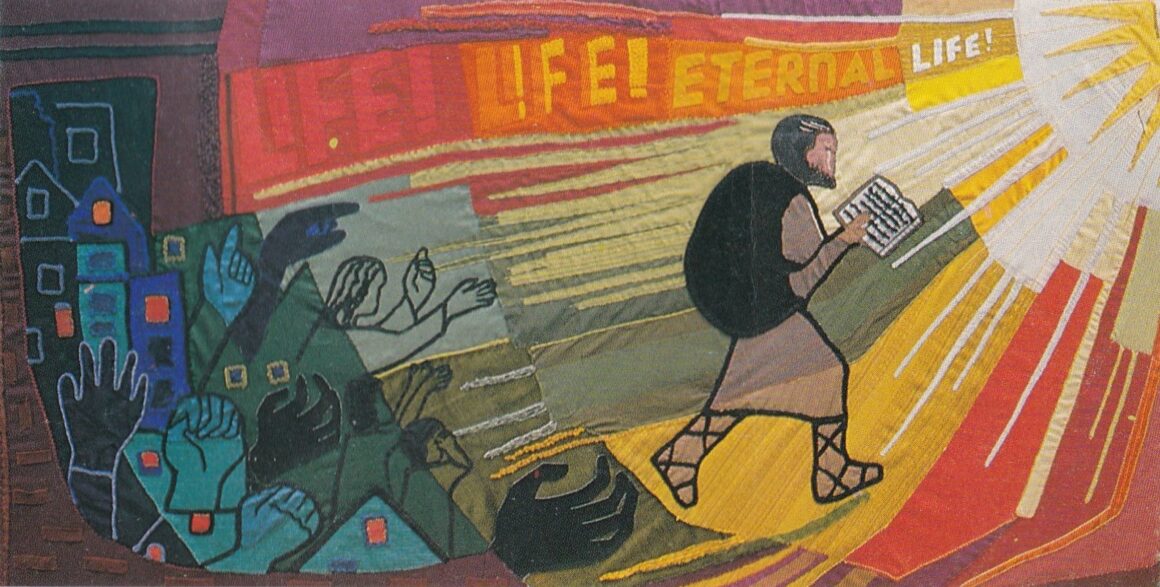

Depictions of everlasting life are the realm of the visionaries and prophets, like the Book of Revelation, like Dante’s Divine Comedy, like C.S. Lewis’s Last Battle, and like John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress. Bunyan’s Christian pilgrim, as he leaves the City of Destruction in this world, cries out “Life, life, everlasting life.” And that is what we are headed toward, together as Christ’s Body the Church.

Brothers and sisters, we have now arrived at the end of the Apostles’ Creed and at the moment of entry of two young citizens of the Kingdom as they begin, or perhaps better, take a step forward toward life, life, everlasting life.