These three sermons concentrate on the central section of the Apostles’ Creed about Jesus Christ, His Incarnation, Atoning Death, Resurrection and Ascension, and His Second Coming in glory.

Immanuel: God with Us, Man for Us

Sermon Preached at Redeemer Anglican Church, Bellevue

July 11, 2021

Seventh Sunday after Pentecost

Lessons: Isaiah 7:14; 9:6-7; Romans 5:12-17; Luke 24: 14-20

In my sermon two weeks ago, I mentioned that the Apostles’ Creed begins by directing our eyes toward heaven and eternity, speaking of God the Father and God the Son. But when it speaks of “Jesus Christ our Lord,” it moves directly to a brief summary of the Gospel narrative of His earthly life in the first thirty years of the first century: “conceived by the Holy Spirit and born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate, died and was buried.”

So let’s consider the Virgin Birth. I chose for our text the Old Testament prophecy from Isaiah chapter 7. Here is the context of this prophecy. In the year 732 BC the mighty Assyrian chariots were bearing down on the petty kingdoms of the Ancient Near East. Sensing their impending doom, the kings of Syria and Israel (the ten northern tribes) tried to force King Ahaz of Judah into a defensive alliance. The plan backfired: in desperation Ahaz appealed to the Assyrians for help. This short-term move by Ahaz would bring long-term consequences, as David’s kingdom ultimately became a vassal state of the Near Eastern empires and then was destroyed in 587 BC.

But the greater problem, according to Isaiah, was not political but spiritual. Ahaz’s deal-making revealed his lack of faith in Yahweh, the nation’s God and protector. So Isaiah warns: “If you do not stand firm in your faith, you will not stand at all” (verse 9). The prophet then promises the King “a sign as deep as Sheol (the realm of the dead), or as high as heaven” to assure him to stand fast. Ahaz, with fake modesty protests: “I will not ask, and I will not put the LORD to the test.” All right, God says, I’ll give you the sign myself: “Behold, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and they shall call his name Immanuel [God with us]” (verse 14).

Like many prophecies, this one had a short-term fulfillment: Ahaz did father a son Hezekiah, who trusted God, and Judah survived for nearly a century after Syria and Israel were wiped off the map. But there was a much higher and deeper fulfilment of this promise, pointing to the messianic King, as announced by the prophet in this familiar text:

For to us a child is born, to us a son is given; and the government shall be upon his shoulder, and his name shall be called Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace. Of the increase of his government and of peace there will be no end, on the throne of David and over his kingdom, to establish it and to uphold it with justice and with righteousness from this time forth and forevermore. The zeal of the LORD of hosts will do this. (Isa 9:6-7)

It was this promise which was fulfilled seven centuries later when the angel Gabriel announced to the Virgin Mary that she would conceive and bear a son named Jesus by the Holy Spirit. Let me draw several connections with the original prophecy. First, the Virgin Birth was initiated by God: “The zeal of the Lord of Hosts will do this.” Secondly, the Virgin Birth, or more precisely the virginal conception of Jesus, was a miracle contrary to the laws of nature. Women do not get pregnant without a man naturally, whatever tricks the magicians in our genetic labs are up to nowadays. Mary’s husband-to-be knew this and needed a dream from on high to prevent him for putting her away (Matt 1:20).

Finally, the prophecy signified that Jesus Christ was True Man and True God from the moment of his conception. The name Immanuel, God with us, meant something far deeper than God’s intervention in the natural process of conception, as was the case with Sarah and Hannah (Gen 18:24; 1 Sam 1:20). While it is beyond any science to determine how God begot Jesus, it is nevertheless true that it was God Himself, God the Holy Spirit, who “overshadowed” Mary. For this reason, the early church revered Mary as Theotokos, “the God-bearer.” But the Creed also says the Son of God was “made Man,” and hence it is equally true that the Mother of God was also the “Man-bearer.” As I mentioned last time, Jesus referred to Himself as “Son of man,” which means “mortal man,” born of woman and subject to the inexorable downward drag of death. Isaiah’s prophecy is further fulfilled when Jesus’ body was buried and He descended in spirit to the realm of the dead (1 Pet 3:18).

The messianic line from David was a line of mortals, and Jesus Christ, the Man Born to be King, was in that lineage. But Jesus’ genealogy, according to Luke, stretches all the way through David to Adam (Luke 3:38). Our Epistle reading lands us right back in Eden. St. Paul says:

Therefore, just as sin came into the world through one man, and death through sin, and so death spread to all men because all sinned – for sin indeed was in the world before the law was given, but sin is not counted where there is no law. Yet death reigned from Adam to Moses, even over those whose sinning was not like the transgression of Adam, who was a type of the one who was to come. (Rom 5:12-14)

Paul’s portrait of Adam is pretty grim. It’s not the lordly Adam walking naked in Paradise; it’s Adam, clothed in shame, fallen into the bondage of sin and death, cursed and cast out of Eden. That Adam, Paul says, is the prophetic figure of the true Son of Man. Adam foreshadows the broken and humiliated corpse of the Man hanging on the Cross.

In linking Adam to the Cross, the New Testament writers were not demeaning Christ or God’s good creation of mankind in His image. Just the opposite: Jesus is the true Man, “one who in every respect has been tempted as we are, yet without sin” (Heb 4:15). The early church father Irenaeus developed a view that Christ “recapitulated,” i.e., passed through, every stage of human life in order to redeem every last crumb of our humanity. A contemporary writer describes the Gospel story as “Jesus becoming Jesus.” I might be so bold as to suggest that it was necessary for Jesus to reach the age of mature adulthood in order to bring us to full maturity “in Christ” (Eph 4:13; cf. John 7:6).

There is a final dimension to the Immanuel prophecy. Jesus is God with us, as we shall be in Him. In another passage, St. Paul says,

Thus it is written, “The first man Adam became a living being”; the last Adam became a life-giving spirit. But it is not the spiritual that is first but the natural, and then the spiritual. The first man was from the earth, a man of dust; the second man is from heaven. As was the man of dust, so also are those who are of the dust, and as is the man of heaven, so also are those who are of heaven. Just as we have borne the image of the man of dust, we shall also bear the image of the man of heaven. (1 Cor 15:45-49)

True humanity cannot be understood only from below. Jesus cannot be understood only as a creature of dust, “from the earth, earthy,” as the King James Version has it. The first Adam, even before the Fall, was incomplete, needing a partner; and even partnered, Adam and Eve were incomplete, grasping at knowledge to live a good life. The second Adam fulfilled the divine image by being a man of the Spirit, conceived by the Spirit, baptized in the Spirit, His words being Spirit and Truth, and finally giving back His Spirit on the Cross. And He has promised His Spirit to those who believe in Him and are born again. Our justification by faith in Jesus, which is once for all, is accompanied by sanctification, which takes time, walking in the footsteps of Jesus. By grace we have been made partakers of the divine nature, being conformed to the image of His Son (2 Pet 1:4; Rom 8:29).

So the Creed teaches us that Jesus Christ is Immanuel, God with us. It also teaches us that He is Man for us, and the Man for others, including our unexpected neighbors who are ready and waiting to hear the Gospel. The Nicene Creed, which supplements the Apostles’ Creed, begins the section on Jesus saying “for us men and our salvation he came down from heaven… and became Man.”

The Creed, I repeat, is all about love, God’s love for us through Christ: “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life” (John 3:16). The love shared among the Divine Persons – the Father, the Son, and the Spirit – is all-sufficient, and out of the overflowing abundance of that love, God reached down in Jesus Christ and lived and died for us. Last week I referred to the hymn which begins:

O love, how deep, how broad, how high,

how passing thought and fantasy,

that God, the Son of God, should take

our mortal form for mortals’ sake!

The hymn continues through the mighty acts of Jesus’ life for us:

For us baptized, for us he bore

his holy fast and hungered sore,

for us temptation sharp he knew;

for us the tempter overthrew.

For us he prayed; for us he taught;

for us his daily works he wrought;

by words and signs and actions thus

still seeking not himself, but us.

Before I conclude, I want to mention one other way Jesus Christ continues to be present with us and for us – and that is in the Holy Communion. As Anglicans see it, He is present with us bodily in the Communion. Our view is a middle way between two misunderstandings. We do not believe that Christ’s presence in the elements of bread and wine can be localized and concretized; that view, called transubstantiation, rationalizes the divine mystery of our union with Christ. On the other hand, His presence is not merely symbolic, a kind of mnemonic device; Anglicans reject that view, called memorialism, which is also rationalistic and shortchanges Jesus’ words of institution when he said: “This is my Body and my Blood.” Anglicans, along with many Lutheran and Reformed Christians, believe in the real and spiritual Presence of Christ in the sacrament. The Risen Christ is seated bodily at the right of God, yet by His Spirit and through faith we participate in His Body and Blood (1 Cor 10:16).

In the Eucharist, Christ is not only present with us, He is present for us, and our proper response to this presence is thanksgiving. That is what the word “Eucharist” means: thanksgiving. That is the spirit of our Eucharistic prayer:

We earnestly desire your fatherly goodness mercifully to accept this, our sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving… Take and eat this in remembrance that Christ died for you, and feed on him in your heart by faith, with thanksgiving…. Drink this in remembrance that Christ’s blood was shed for you, and be thankful.

To sum up, the Creeds teach that Jesus Christ is the promised Immanuel – God with us – conceived by the Holy Spirit and born of the Virgin Mary. He is also the true Man given for us on the Cross and present in the sacrament of His Body and Blood. In light of this, let us now in the words of the Prayer Book “draw near with faith and take this Sacrament to our comfort.”

“When I Am Lifted Up…”

Sermon Preached at Redeemer Anglican Church, Bellevue, PA

July 18, 2021

Eighth Sunday After Pentecost

Lessons: Isaiah 52:13-53:1-6; Romans 6:1-11; Luke 24:36-53

I grew up as an unbeliever and only became a Christian and was baptized and confirmed when I was half-way through college. So I have this little doubting Thomas voice etched in my conscience that can comprehend the question “Is it true?” “Is God for real?” By contrast, my wife Peggy was a cradle Christian, Episcopalian in fact. When she was in college, in response to a class lecture, she tried to think as if God didn’t exist; she lasted only a day or two before giving up the experiment. God just had to be there!

The revolution in my thinking was not just about God but about Jesus. In my preteen years, I attended a Unitarian Sunday school (Unitarians, it is quipped, believe in no more than one God). I remember they had us read the earliest Gospel of Mark where Jesus cries, “My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?” and where on Easter morning, the story ends abruptly with the women running away in fear because they had come to the wrong tomb. Then they took us to the latest Gospel of John where the Risen Jesus is walking through walls, telling Thomas to stick his hand in the nail- and spear-holes from the Cross and then levitating out of sight. You see, they said, the early Church perverted the kindly moral teacher of Nazareth into the walking and talking God of the Creeds. (A decade later, when I went to seminary, I learned a gussied-up name for this view. It’s called “the development of Christology.”)

Back to my conversion. When I began to read the whole Bible for myself, I found a very different portrait of Jesus Christ and came to the conclusion that C.S. Lewis was right when he said Jesus either was mad or he was bad or He was God. The Creeds come down squarely on the “God” side of this matter: the Son of God is of one Being with the Father and begotten of the Father from all eternity. Equally, the Creeds say that Jesus Christ our Lord was fully human, conceived by the Holy Spirit and born of the Virgin Mary, and that He suffered and was crucified, dead and buried under Pontius Pilate, the Roman Procurator in Palestine in 30 AD. When He rose from the dead and ascended into heaven, He did so in His human (if glorified) body.

Last week I described Jesus’ incarnation not just as the moment of his virginal conception (true though it is) but as “Jesus Becoming Jesus.” With some fear and trembling (for who can know the mind of the Lord?), I am suggesting that Jesus came to discover and His own identity, mission, and destiny as He lived out His life, and over the course of three years He conveyed this life to His apostles, who in turn passed them on to us in the New Testament. This apostolic Good News about Jesus is summarized in the Creeds and is the only reason on this earth that we have hope for eternal life with God (John 3:16).

Surely the most important influence on the boy Jesus was his immersion in the Scriptures of the Old Testament. By the age of twelve, He was already confounding the Jewish teachers of the Law with His mastery of the Bible. He was already a rabbi, a prodigy. But beyond His comprehensive knowledge of Scripture, Jesus brought an inspired insight that was utterly unique, and this insight is at the heart of the Gospel and of the Creeds. It is found in our reading today from the prophet Isaiah. This insight is a “news flash,” indeed a Good News flash from God.

The Book of Isaiah has sometimes been called “the fifth Gospel” because it is filled with prophecies of Christ. Last week we read from early chapters which speak of the Virgin Birth of a Son whose name Immanuel means “God with us” and whose titles are “Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace” (Isa 7:14; 9:6). This is the classic description of the Messiah, the greater Heir of David’s line: the government of the universe, not just of Israel, will rest on his shoulders. Jewish interpreters took these titles as hyperbole. The Messiah was god-like, but not God Himself.

But Jesus understood the prophecy literally: God Himself was coming in person. In chapter 40, God instructs the nation to bear witness to God’s coming: “Get you up to a high mountain, O Zion, herald of good news … say to the cities of Judah, ‘Behold your God!’” (Isa 40:9). The Good News – and I think Jesus read it this way – is that God the Divine King is coming in Person to save His people and indeed the whole world. This insight is revolutionary, and if false, it is blasphemous: the Messiah and the Great I AM are one and the same.

Jesus noted something else equally radical in this latter section of the book of Isaiah. Embedded in it are four passages describing a figure called “the Servant of the Lord.” Modern scholars call these four texts “Servant Songs” (Isa 42:1–4; 49:1–6; 50:4–7; and 52:13–53:12). When we first meet the Servant in chapter 42, he is identified with the people of Israel, recalling God’s promise to Abraham that in his seed the nations of the world would be blessed (Gen 12:3). Now the Lord repeats this promise to his Servant: “I will make you as a light for the nations, that my salvation may reach to the end of the earth” (Isa 49:6). Why do I think Jesus knew this passage? We can hear in it an echo of Jesus’ Great Commission to go into the world and preach Good News to the nations.

The prophecy is not just about the Great Commission. It’s about the great Commissioner, who speaks as God: “All authority in heaven and earth are given to me,” Jesus says. Isaiah’s vision of the messianic Son of God, born of a Virgin, was confirmed when Jesus was baptized and the Father’s voice from heaven said: “You are my Son: this day I have begotten you.” For most Jews, the title Son suggested the power and majesty of the coming Messiah, the second King David. But Jesus – and only Jesus – turned the title “Son” into “Son of Man,” the second Adam, fallen and born to die, and He alone linked Isaiah’s messianic title “Son” with that of “Servant,” i.e., God’s slave.

That’s not all. Jesus went one step further when He identified the “Servant” with suffering and shame. We see this theme most clearly in the final Servant Song in Isaiah, chapters 52-53, which is our text today. The Song begins with a glorious vision: “Behold, my servant shall act wisely; he shall be high and lifted up” (Isa 52:13). But right alongside this vision of glory comes a vision of, well, ugliness: “he had no form or majesty that we should look at him,” Isaiah says, “no beauty that we should desire him… his appearance had been marred beyond human semblance” (Isa 53:12,14).

This paradox of the Servant’s glory and ugliness comes as an utter surprise to the earthly kings, who confess; “He was despised and rejected by men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief; and as one from whom men hide their faces he was despised, and we esteemed him not” (53:3). “We didn’t get it,” the ancient potentates say. And they were not the only ones. My Unitarian Sunday School teacher didn’t get it. My “death of God” seminary professor didn’t get it. I didn’t get it, but for the grace of God.

The Song then moves to one even more marvelous feature of the Servant’s suffering and grief: it was not for his sins but for ours:

Surely he has borne our griefs and carried our sorrows; yet we esteemed him stricken, smitten by God, and afflicted. But he was wounded for our transgressions; he was crushed for our iniquities; upon him was the chastisement that brought us peace, and with his stripes we are healed. (53:4-5)

Jesus alone saw the Servant’s great work as one of vicarious suffering, of atoning for the sins of others.

Finally, the Song states that this suffering was not accidental, but the very will of God: “All we like sheep have gone astray; we have turned – every one – to his own way; and the LORD has laid on him the iniquity of us all” (verse 6).

Now, friends, let me say this – as one who bears the title “Professor of Biblical Studies”: there is no other passage like Isaiah 53 in the Old Testament. Jews in Jesus’ day and down to the present, refuse to accept its clear meaning. And they are not the only ones: Jesus’ own disciples missed the point. When James and John ask to sit at Christ’s right hand in glory, He rebukes them, saying: “the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many” (Mark 10:45).

I believe that Jesus, and He alone, came to understand this prophecy to be referring to Himself. As Jesus and His disciples journeyed toward Jerusalem for Passover, He predicted that He would be handed over to the chief priests and crucified and on the third day rise – but they did not understand Him (Mark 9:32). Then on Easter evening, three days after His Crucifixion, Jesus appeared at Emmaus and “opened their minds to understand the Scriptures,” saying to them: “Thus it is written, that the Messiah should suffer and on the third day rise from the dead” (Luke 24:45-46). Forty days later, Jesus ascended into heaven, having told them to wait in the city until they were empowered by the Holy Spirit to preach the Gospel to the ends of the earth.

In John’s Gospel, Jesus conflates the crucifixion, resurrection, and ascension into one image of being “lifted up.” He tells Nicodemus:

No one has ascended into heaven except he who descended from heaven, the Son of Man. And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life. (John 3:13-15)

This is a strange yet powerful picture of the vicarious atonement: Jesus, the cursed snake, is lifted up on the Cross for the healing of the people. Again, as He entered Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, Jesus announced the coming world-historical crisis, saying, “Now is the judgment of this world; now will the ruler of this world be cast out. And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all people to myself” (John 12:31-32).

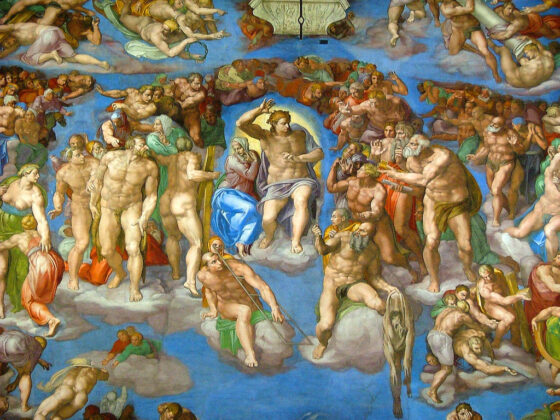

Have you noticed that there are three kinds of cross in Christian churches? In Catholic churches the crucifix depicts the broken body of Jesus; in Protestant churches the empty cross reminds us the empty tomb on Easter morning; and in Eastern Orthodox churches the “Christus Victor” cross show Christ enthroned in glory and conquering the powers of darkness. In the same way, I think the Apostles’ Creed expresses in one extended sentence the single “lifting up” of the Son of God: “suffered under Pontius, Pilate, crucified dead and buried, risen from the dead and ascended to the right hand of God the Father Almighty.”

There is one final implication of the Isaiah passage, which Jesus foresaw. At the end of this song, God vindicates the Servant and extends the benefits of saving work to sinners. He announces:

Out of the anguish of his soul … the righteous one, my servant, will make many to be accounted righteous, and he shall bear their iniquities. Therefore I will divide him a portion with the many, and he shall divide the spoil with the strong, because he poured out his soul to death and was numbered with the transgressors; yet he bore the sin of many, and makes intercession for the transgressors. (verses 11-12)

This is why Isaiah is called the fifth Evangelist, because he preaches the justification of the ungodly through the atoning death of Christ. In our baptism, we are symbolically reenacting the death, resurrection and ascension of Christ. In our Epistle today, Paul says:

Do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death, in order that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life. For if we have been united with him in a death like his, we shall certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his. (Rom 6:3-5)

The difference, of course, is that we are still on this side of the valley of the shadow of death, while the Risen Lord is on the other side. But, Paul asserts, when we believe in Jesus Christ, when we walk by faith, we have the assurance of eternal life with him:

Now if we have died with Christ, we believe that we will also live with him. We know that Christ, being raised from the dead, will never die again; death no longer has dominion over him. For the death he died he died to sin, once for all, but the life he lives he lives to God. So you also must consider yourselves dead to sin and alive to God in Christ Jesus. (Rom 6:8-11)

This is the basic believing we confess as Christians. Are we putting our lives in hands of a badman or a madman? Many in the ancient world thought it immoral and crazy to worship a crucified criminal, the so-called King of the Jews. Many in our world think so too. This is the scandal of the Gospel, as Paul expresses it:

For the word of the cross is folly to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God. For the foolishness of God is wiser than men, and the weakness of God is stronger than men. (1 Cor 1:18,25)

What about you? Are you still a doubting Thomas? Don’t let Thomas’ little voice prevent you from the promise: “Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed” (John 20:29). As those who have been baptized into Christ and who now walk in newness of life, let us join with St. Paul in saying: “Thanks be to God for His expressible gift!” (2 Cor 9:15).

He Shall Come Again in Glory

Sermon Preached at Redeemer Anglican Church, Bellevue

August 8, 2021

Tenth Sunday after Pentecost

Lessons: Daniel 7:9-14; 1 Corinthians 15:50-58; Mark 13:23-32

After a two-week intermission, I am returning today to the Apostles’ Creed and in particular to the final phrase of the section on Jesus Christ our Lord, which reads: “he will come again to judge the living and the dead.”

This brief phrase is a summary of what theologians called eschatology, or “the last things”: death, judgment, heaven and hell. Let’s begin by admitting that there is much about these last things which is a mystery. The folk singer Iris DeMent puts the matter this way:

Everybody is a-wonderin’ what and where they all came from,

Everybody is a-worryin’ ’bout where

They’re gonna go when the whole thing’s done,

But no one knows for certain and so it’s all the same to me –

I think I’ll just let the mystery be.

While I agree that many of the last things are mysterious, I don’t find that people are a-wonderin’ and a-worryin’ enough about where they’re gonna go when the whole thing’s done. Rather, I think our society is in a state of denial. If “letting the mystery be” means a kind of collective shrug of the shoulders, many are going to wake up some day to profound regret.

As Christians, we may certainly ask the questions “how,” “why,” “when,” “where” about the last things – and I shall be coming back to these – but the fundamental question has to do with “Who” holds the future. That Person is Jesus Christ.

But did this last phrase from the Apostles’ Creed come from Jesus? Yes, it did. He said so repeatedly to His disciples, as is the case in our Gospel text today. In the last days, He says, “they will see the Son of Man coming in clouds with great power and glory.”

So how did Jesus come to know this? These past weeks I have been speaking about “Jesus becoming Jesus,” how as the fully human and incarnate Word, Jesus learned about His identity and mission through the Hebrew Bible, the Old Testament. Earlier I suggested that Jesus learned from the book of Isaiah about His role as the Suffering Servant, who would give His life as a ransom for many.

Our lesson today from the book of Daniel is a second text which I think formed Jesus’ sense of His final coming in glory. Daniel chapter 7 describes a vision of the climax of world history in terms of four empires, increasingly tyrannical and culminating with a supreme Despot who forbids God’s Law, persecutes God’s people, and sets an idol of himself in God’s Temple. This figure is the Antichrist later described in the Book of Revelation as the Satanic beast. Now back to Daniel. At the climax of the vision, God Himself appears as an Ancient of Days – a all-powerful heavenly Patriarch – coming in glory to judge these evil empires. But He is not alone when he appears:

with the clouds of heaven there came one like a son of man, and he came to the Ancient of Days and was presented before him. And to him was given dominion and glory and a kingdom … and his kingdom is one that shall not be destroyed. (verses 13-14)

What is striking about this vision – and I think this is how Jesus understood it – is that the second figure is “a son of man,” that is, he is human, not a spirit or an angel. No, he is born of a woman, he is mortal, subject to the power of death. This vision answers the question posed in Psalm 8: “What is man that you are mindful of him, the son of man that you visit him?” The answer to this question is the One who is both Son of God and Son of Man, Jesus Christ.

There is a second striking question raised in of Daniel’s vision: is this son of man ascending to the throne of the Ancient of Days or descending with Him to judge the earth? Maybe both, like the angels ascending and descending on Jacob’s ladder (Gen 28:12; cf. John 1:51). What Jesus and the Creed are saying is that the mission of God’s Son involved an ongoing movement from heaven to earth and back again, as the song says:

You came from heaven to earth, to show the way

From the earth to the cross, my debt to pay

From the cross to the grave, from the grave to the sky…

And there is a grand finale to this movement: His glorious return to judge the living and the dead.

So now that we know the Who who spoke of His coming again, let’s take a look at the questions: “how?” “why?” “when?” and where?” of the Last Things.

How will Christ return? The Nicene Creed adds the little phrase: He will come in glory. Jesus Christ is the radiance and exact imprint of the Father’s glory, which He possessed before all time (Heb 1:1-4). It is the glory He suppressed when He humbled Himself to be born in a stable in Bethlehem and to live the life of a servant (Phil 2:5-7). It is the glory which flashed forth momentarily on the Mount of Transfiguration. It is the enduring glory He received when He sat down at the right hand of the Father’s throne after the resurrection. And then there is the end. Jesus predicts an astounding explosion of that glory, saying: “Then will appear in heaven the sign of the Son of Man, and then all the tribes of the earth will mourn when they will see the Son of Man coming on the clouds of heaven with power and great glory” (Matt 24:30).

Why will Christ return? He will come again in glory “to judge the living and the dead,” that is, to judge every man and woman living or dead. (This clause, incidentally, upholds the biblical and historic Christian teaching that the human person is both body and soul. The body dies and is buried; the soul lives on in some state until the Day of Judgment.)

The idea of God as judge pervades the Bible. God is good and made all things good, but there is an Enemy who has rebelled against God and tempted mankind into sin. Calling Adam and Eve to account, God judges them with the wages of sin, which is death, from Eden on. In His mercy, God did not leave us dead in our sins and without hope, but He sent His Son to bear the judgment that should have been ours. And now, having raised Him from the dead, the Father has entrusted final judgment to His Son.

What is the basis for this final judgment? In Daniel’s vision, it states “the books were opened”; the same phrase used by John in the Book of Revelation:

And I saw the dead, great and small, standing before the throne, and books were opened. Then another book was opened, which is the book of life. And the dead were judged by what was written in the books, according to what they had done. (Rev 20:12)

Here is how I understand these account books. Those whose names are written in the book of life are the redeemed, those who have put their trust in the Lamb that was slain. Jesus is the way, the truth and the life; no one comes to the Father except through Him (John 14:6). At the same time, no good deed goes unrewarded in God’s eyes, nor is any sin overlooked. It is my view that even for believers there is a purging, a refining of sin, but in a strange sense we shall wish to be cleansed from our impurities (cf. 1 Cor 3:12-13).

What God desires is that believers repent of evil and do good, and that unbelievers repent and come to Christ. The ultimate sin, the sin of Satan, is to know God and refuse Him. So long as a person lives, the door remains open and Christ is knocking and asking to enter his heart. Without repentance, the verdict is sealed in the Second Death, which is separation from God in hell.

This leads to the next question: when will Christ come to judge? The Old Testament prophets speak repeatedly of the Day of the Lord coming at a time of God’s sovereign reckoning. As for the date and time of this coming, Jesus says in today’s Gospel reading: “Concerning that day and hour no one knows, not even the angels of heaven, nor the Son, but the Father only” (Matt 24:36). He goes on to say that the end will come as a complete surprise:

“For as were the days of Noah, so will be the coming of the Son of Man. For as in those days before the flood they were eating and drinking, marrying and giving in marriage, until the day when Noah entered the ark, and they were unaware until the flood came and swept them all away, so will be the coming of the Son of Man.” (verses 37-39)

So stay awake, Jesus says, for you do not know on what day your Lord is coming. (verse 42).

Another way of looking at this question is to say that we should consider the day of the Lord’s coming for us to be the day of our death. If somehow we are alive at that time, our situation before the Judge is no different. When I was a small boy, I somehow learned the prayer:

Now I lay me down to sleep,

I pray the Lord my soul to keep.

If I should die before I wake,

I pray the Lord my soul to take.

I suspect today this prayer is considered too scary for children. In earlier times and even in many parts of the world today, surviving to the next day, especially for children and the poor, is hardly to be assumed. And in any case, each one of us, young or old, has a due date with God. Forgetting this reality is part of what I am calling our collective amnesia. Think of those occupants in the condo collapse in Florida recently. They fell asleep in this world and woke up in another. So, Jesus says, keep awake with God, even as you sleep.

Now to a final question: where does the judgment take place? According to Daniel’s vision, God comes “with the clouds of heaven.” We naturally think of heaven as being “up there,” but only silly literalists were disturbed when Yuri Gagarin, the first man in space, reported back: “I looked and looked and looked and looked, but I did not see God.” Thoughtful Christians have always understood that heaven is a different dimension of reality from the up-down of our material world.

And the same distinction goes for the “where” of our final state. Going to heaven is not a change of location but a change of nature. When we speak of going to heaven when we die, we do not mean floating on clouds playing harps. The new creation, as we see in the final vision of the Book of Revelation, is not fluffy like a Hallmark card but something utterly foreign, a transformation of the good world God created in the beginning into something so marvelous that it can only be described in metaphors.

St. Paul puts it this way in our Epistle today:

Behold! I tell you a mystery. We shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet. For the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised imperishable, and we shall be changed. For this perishable body must put on the imperishable, and this mortal body must put on immortality. (1 Cor 15:51-53)

In The Last Battle, the finale of C.S. Lewis’ Narnia books, the victors find themselves in front of a door. Suddenly the great lion Aslan, the Christ-figure, appears and roars: “Now it is time!” And the door opens. As Aslan stands in the door, all the creatures come streaming toward him. Judgment happens when they enter in at the door (or swerve away from it); but this is just the beginning of the end. “Further up and further in!” is Aslan’s cry to those pilgrims as they climb to higher and higher vistas. And as they do, they begin to meet other residents of Narnia from earlier stories and ages who are being transformed. The Apostles’ Creed returns to this glorious subject in its last phrases about “the communion of saints” and “life everlasting,” and we’ll return to it later too.

So let’s come back to earth here and now. There is perhaps a proper Christian way to “let the mystery of the last things be.” In the next section of the Creed, we encounter the Third Person of the Trinity, who will dwell in our hearts as we await the glorious coming of our Lord Jesus Christ.

Without forgetting the glorious hope of Christ’s Return, we now return to our daily journey of faith, hope and love.

Maranatha! Come, Lord Jesus!