“This day you will be with me in Paradise.”

I preached this sermon on Good Friday 2017 at my home parish in Pennsylvania. Since it speaks of an event subsequent to Jesus’ death, it seems an appropriate to consider it an appropriate link to Holy Saturday.

In Holy Week we are invited to enter with joy into the contemplation of the mighty acts by which God offers us salvation and eternal life. In that spirit, I would ask you to imagine the conversation on Calvary between Jesus and a man I am calling “the Prodigal Terrorist.”

Of the Seven Words, this is the only conversation on the Cross, and it is an elevated conversation. Jesus and the two criminals are literally talking above the heads of all others, suspended, as it were, between earth and heaven. This is appropriate because Jesus’ Word here has to do with heavenly matters: “Truly I say to you,” he swears to one of the men, “today you will be with me in Paradise” (Luke 23:43).

So who were these fellows who were crucified with Jesus? Traditionally, they have been called “thieves,” but this description is inexact. The Romans seldom crucified pickpockets and reserved the cross for rebels against the Roman order (the so-called “Pax Romana”). More likely, Jesus’ companions on Calvary were accomplices of Barabbas, of whom it is said “he committed murder in the insurrection” (Mark 15:7: John 18:40). Barabbas’ insurrection was probably related to the so-called “Zealot” movement, Jews determined to bring in God’s kingdom by violence, much as today’s ISIS terrorists use violence to establish the Muslim caliphate. Indeed, one branch of zealots was named “sicarii” after the curved dagger they used to murder their opponents. So Jesus was crucified with two terrorists and indeed was substituted for their ringleader.

According to Matthew’s Gospel, both these men cried out scornfully at Jesus (Matthew 27:44). What exactly were they saying? Luke tells us: “Save yourself and us!” These words are almost identical to the mocking words of the bystanders below: “He saved others; he cannot save himself. If he is the King of Israel; let him come down now from the cross, and we will believe in him” (Matthew 27:42). Except that perhaps the terrorists actually believed, or hoped, that Jesus was the hidden Messiah and would come down from the Cross, overthrow the Romans, and bring in the end-time Kingdom. “Save us” could be a battle-cry, with the “us” being them and their movement.

Were the Evangelists confused over whether one or two of the crucified men cursed Jesus? I don’t think so. My answer to this apparent discrepancy is simple: both men were desperate. It is well known from the annals of wickedness that torture is never merely physical but also psychological and that under torture even the bravest will say just about anything. Now the thieves on the cross hung for three hours with Jesus, and there is no reason to think they did not endure major mood swings. The one constant object of their tortured vision was Jesus of Nazareth and his title King of the Jews. It is not surprising that the so-called penitent thief, along with the other, railed at Jesus, demanding he perform a miracle and come down. He was, like the Prodigal Son of Jesus’ parable, at the end of his rope.

And then like the Prodigal, something changed in that man’s heart. “Save us” morphed into: “Jesus, remember me.” What caused him to change from cursing Jesus to confessing Jesus? Was it not God’s grace reflected in the Crucified One? Was it not amazing Grace flowing from heavenly Love? Remember Jesus’ words when Peter confessed Him as Lord: “Flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but my Father in heaven” (Matthew 16:17). So here God opened a violent man’s eyes to see Jesus, the innocent Man for others, who prayed: “Father, forgive them.” “Yes,” the man said to himself, “forgive them means forgive even me.”

To this desperate man, Jesus made a simple but emphatic promise: “Today you will be with me in Paradise.” What did he mean by “today”? I take it to mean that day, the first Good Friday, but it also meant the long-expected Day of the Lord, when God would set all things right. What did he mean by “paradise”? The word means literally “a garden” or better, “a park,” the kind of cultivated wilderness one finds inside the gates of great estates. The most famous biblical park is Eden, from which our rebellious ancestors were expelled. In Jewish lore paradise came to be seen as the gate area of heaven, to which a few elect heroes – Abraham, Enoch, Moses, Elijah – were granted special entry. Everyone else descended to Sheol, to Hades, the place of the dead, where they awaited, either in hope or in torment, the Day of Resurrection.

Jesus himself referred to Paradise in his parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19-31). The Rich Man died and was buried and went straight to Hades. Lazarus, the beggar outside the Rich Man’s gate, was conducted by angels directly through the gates of Paradise and into “Abraham’s bosom.” We cannot miss the irony of this theme: the first in this world – the “quality folks” – will be last, and the last – the most deplorable of deplorables – will be first, right up there with Father Abraham.

Now of course, the beggar is only a figure in Jesus’ Parable and the man on the Cross, like Jesus, was a real person in history; but for us who read Scripture as God’s Word, the figural – the beggar Lazarus and the Prodigal Son – and the real – the man born blind, the Samaritan woman at the well, the woman accused of adultery, oh yes, and the zealous Pharisee Saul – come together as “types,” as examples for the ages. So also the “penitent thief” became a type, the patron saint of last-second conversions.

A couple weeks ago, my wife and walked up in Sewickley Cemetery and stopped at the memorial of those who died in 1994 in USAir Flight 427. One of most modern people’s vivid fantasies, I think, is to be sitting helplessly in a plane falling from the sky. How many on that flight may have turned to the Lord and cried “Jesus, remember me…”? It’s a bad idea to wait until the last second to do anything, including turning to God, but it is better than not turning to Him. In any case, this Word is a reminder to all of us that, however long we have believed and however much we have done, our salvation is grounded, nothing more, nothing less, in the shed blood of Jesus Christ. As the hymn puts it: “Nothing in my hand I bring; simply to Thy Cross I cling.”

This week we contemplate in our mind’s eye the mighty acts of God all the way to Easter Day. Let me leave you with a fantastic vision. What if the other man, the impenitent thief, overheard the conversation between Jesus and his companion and turned to Jesus in his final breath. Would he not also have entered Paradise? Of course he would! – which leads to this strange vision. Just imagine Jesus, having descended to Hades on Holy Saturday, coming home with the souls of all the faithful departed who awaited His Coming and being greeted at the gate of Paradise by two Prodigal Terrorists singing “O When the Saints Come Marching In”? Did it happen that way on the first Easter? Why not? Do you want to be in that number? Then come and enter, enter his gates with thanksgiving.

Collect for Good Friday

Almighty God, we beseech you graciously to behold this your family, for whom our Lord Jesus Christ was willing to be betrayed and given into the hands of sinners, and to suffer death upon the Cross; who now lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

Today’s hymn is Abide with Me.

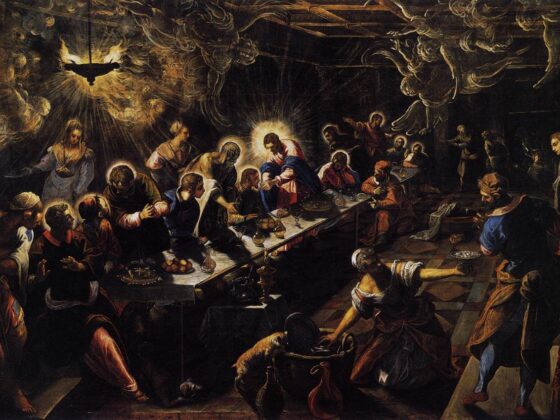

Cover Art is Rubens, Christ Between Two Thieves (Wikimedia)