Justin Welby, the Archbishop of Canterbury, recently issued a press report about how he experiences God as father:

The Most Revd Justin Welby said that calling God “father” for him means that “here is one that is perfect, that loves me unconditionally, that reaches out to me and knows me better than I know myself and yet still loves me profoundly.”

But the Archbishop also said that God is not a father in the same way that a human would be – and that descriptions of God are always “to some degree metaphorical”.

Speaking at St Martin-in-the-Fields in London on Monday evening, Archbishop Justin said: “It is extraordinarily important as Christians that we remember that the definitive revelation of who God is was not in words, but in the word of God who we call Jesus Christ. We can’t pin God down.”

He added: “God is not a father in exactly the same way as a human being is a father. God is not male or female. God is not definable,” he said.

Archbishop Welby’s answer touches on a concern I have expressed before: that of the Persons of the Triune Godhead, the Father is the most obscure and in our day the most offensive. Indeed, the Person of the Father is inherently mysterious, and Archbishop Welby is correct that we can only come to the Father through the Son, but I think the Archbishop’s response to the question of God as father seems more an apology than an apologia.

Jesus’ first adult act was to search the Scriptures with the teachers of the Law (Luke 2:46-49), which is also the first recorded occasion of His astounding reference to God as “my Father.” In this spirit, I am proposing three brief biblical reflections: on the Name of the Father, on the Image of the Father, and on the Authority of the Father.

The Name of the Father

While God in the Old Testament is the one and only God, utterly above all other so-called gods (Deuteronomy 6:4; Psalm 89:6-8), His Name is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. He is the God of the burning bush, who names himself “I AM” (Exodus 3:13-14), the source of being. The Third Commandment prohibits speaking His Name in vain, and from early on Jews used circumlocutions for the Name YHWH, speaking of Him as “the Name” (ha-shem) or “the Lord,” as witnessed in the Greek Bible (ho kyrios).

Marc Chagall, Exodus: Moses and the Burning Bush (Flickr)

The Old Testament occasionally uses “father” and less occasionally “mother” to characterize His calling and care of His people (Exodus 4:23; Deuteronomy 32:6; Isaiah 49:15). More pertinently, God announces Himself as father to Israel’s anointed King (2 Samuel 7:14; Psalm 2:7). But no one in the Old Testament ever speaks of God as “my Father” in the way Jesus does. In one telling dispute, Jesus accuses His Jewish opponents of having the devil for their father. They respond awkwardly: “We have one father, even God”; and Jesus replies: “If God were your Father, you would love me, for I came from God and I am here. I came not of my own accord, but he sent me” (John 8:41-42).

Uniquely, Jesus prayed to Abba, “dear Father.” This was the Name He taught His disciples to hallow (Matthew 6:9; Luke 11:2). This was the Father He pleaded with in the Garden of Gethsemane (Mark 14:36) and the Father with whom He interceded from the Cross on behalf of His enemies and to whom He commended His soul unto death (Luke 23:34,46). St. John describes the Passion in terms of the reciprocal glorification of the Father and the Son:

Now is my soul troubled. And what shall I say? “Father, save me from this hour?” But for this purpose I have come to this hour. Father, glorify your name. Then a voice came from heaven: “I have glorified it, and I will glorify it again.” (John 12:27-28; cf. Mark 14:36)

Jesus shared the Father’s Name with the Church: “Holy Father, keep them in your name, which you have given me, that they may be one, even as we are one” (John 17:11). The Triune Person who conveys the divine Name is the Holy Spirit: “The Helper, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, he will teach you all things and bring to your remembrance all that I have said to you” (John 14:26). The Church has no inherent right to pray as Jesus did, which is why “we are bold to pray, Our Father.”

According to apostolic tradition, the proper name of God is “Father” and the proper title of Jesus is “Lord” (Romans 8:15; 1 Corinthians 12:3). Thus St. Paul’s normal congregational greeting is: “Grace to you and peace from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ” (Romans 1:7; Galatians 1:3 et al). The Father gladly shares Deity with Jesus, the Son of God (Romans 1:4; 9:5), as is clear in the early Christ-hymn of the Son’s self-emptying and exaltation:

Therefore God has highly exalted him and bestowed on himthe name that is above every name [i.e. the Name], so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father. (Philippians 2:9-11)

Whether the exalted Name referred to in this text is “Jesus,” “Lord,” or “God,” the Father bestows it and receives glory thereby. Similarly, the Holy Spirit, who proceeds from the Father, empowers believers, His adopted sons in Christ, to address Him as “Abba! Father!” (Romans 8:15; cf. Galatians 4:6).

The Image of the Father

In the Old Testament not only is God’s Name unknown but His Person is unseen. As the Third Commandment forbids false speech about God, so the Second Commandment forbids any image of Him. While theologians may speak of knowing God in terms of His attributes – His holiness, omnipotence, righteousness and the like – the Bible, it seems, places the emphasis on seeing God. And in the case of God the Father, this basically means not seeing Him. God the Father is fundamentally incomprehensible and is best approached by what He is not, the so-called via negativa. For the unbeliever, the conundrum of the Unknown God may lead to atheism or mysticism, but for the Christian it leads another way, to repentance and faith in the Risen Christ (Acts 17:21-31).

The Prologue to John’s Gospel (John 1:1-18) reintroduces God from the beginning. He is the Word who is with God and who is God (verse 1). He is the true Light (verse 9). He is the Word made flesh, the only Son of the Father (verse 14). He is Jesus Christ (verse 17). The Prologue concludes: “No one has ever seen God; the only-begotten God, who is at the Father’s side, it is He who has made Him known” (verse 18). The unseen Person of the Father is now known in the Person of His incarnate Son.

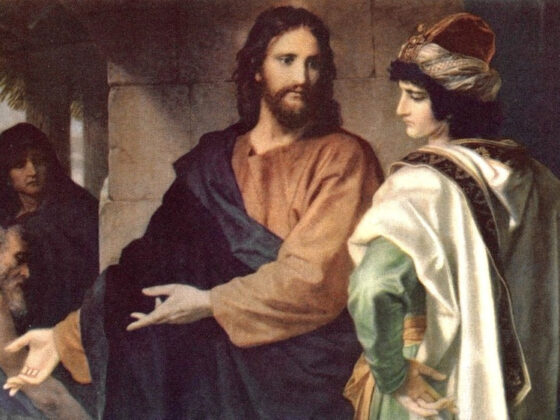

Throughout the apostolic writings, the Father is known only as He is imaged in the Son. John reports this conversation between Jesus and Philip:

Philip said to him, “Lord, show us the Father, and it is enough for us.” Jesus said to him, “Have I been with you so long, and you still do not know me, Philip? Whoever has seen me has seen the Father. How can you say, ‘Show us the Father’?” (John 14:8-9)

Philip’s blindness, while understandable, is a token of heresies to come. Failure to acknowledge the Father as the Father of the Son and the Son as the Son of the Father has severe spiritual implications: “This is the antichrist, he who denies the Father and the Son. No one who denies the Son has the Father. Whoever confesses the Son has the Father also” (1 John 2:22-23). Likewise the “Athanasian Creed” states: “This is the catholic Faith, which except a man believe faithfully, he cannot be saved.”

Two other New Testament authors make the same point as St. John about seeing the Father in the Son. St. Paul writes of Jesus Christ:

He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation. For by him all things were created, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or authorities – all things were created through him and for him. And he is before all things, and in him all things hold together. (Colossians 1:15-17)

The “invisible God” is the Father, whose creative work – things visible and invisible – is carried out by the Son, who is His perfect image. Elsewhere, Paul compares the hidden God of the Mosaic dispensation and of this present age with the new dispensation of “the gospel of the glory of Christ, who is the image of God… For God, who said, ‘Let light shine out of darkness,’ has shone in our hearts to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ” (2 Corinthians 4:4,6).

Similarly, the author of the Letter to the Hebrews begins:

Long ago, at many times and in many ways, God spoke to our fathers by the prophets, but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son, whom he appointed the heir of all things, through whom also he created the world. He is the radiance of the glory of God and the exact imprint of his nature, and he upholds the universe by the word of his power. (Hebrews 1:1-3)

Jesus Christ is the perfect “icon” of the Father. He is, as the Nicene Creed states, “Light from Light.” For Gregory Nazianzen, the nature of light – “in your light we see light” (Psalm 36:9; cf. John 1:9; 1 John 1:5) captures the essence of the divine relations: “We receive the Son’s light from the Father’s light in the Spirit’s light” (Oration 31.3). The love of the Father is returned reflexively by the love of the Son in the love of the Holy Spirit.

Prophetic visions of God portray the Person of the Father obliquely, as it were from behind (Exodus 33:18-21), yet they do point to aspects of His identity. In the dream vision of Daniel 7:9-14, the Most High God appears as an “Ancient of Days,” a Patriarchal King. He is hardly a feeble codger: “his clothing was white as snow, and the hair of his head like pure wool; his throne was fiery flames; its wheels were burning fire.” Then a “Son of Man,” i.e., a mortal man born of woman is presented and enthroned before this Patriarch. The Son of Man is not only an individual but the Man who represents God’s people, the “saints of the Most High” (Daniel 7:22-27; 12:1-3).

God the Father is not a man. He is masculine. Jesus Christ was a mortal man, born of Mary of Nazareth and Mother of God. He was and is masculine. He is the eternal Son of the Father and the second Adam, very God and very Man. God’s masculinity is inclusive and archetypal. The Father has innumerable adopted sons, male and female. Jesus has innumerable brothers, male and female.

(Through most of history and even today in many cultures, representative language for God and man has been understood as truly inclusive. In order to highlight the archetypal reality that corresponds to this language, I have chosen to employ the “honorific” capitalization for God and Christ.)

The Authority of the Father

The Father is the Divine Archetype, “the one God and Father of all, who is over all and through all and in all” (Ephesians 4:6). This understanding of God the Father underlies two passages from St. Paul concerning the Father’s authority.

The first text comes from an oblique reference – oblique in the sense that Paul is not teaching but praying and in so doing assumes the nature of the Father:

For this reason I bow my knees before the Father, from whom every family in heaven and on earth is named, that according to the riches of his glory he may grant you to be strengthened with power through his Spirit in your inner being, so that Christ may dwell in your hearts through faith–that you, being rooted and grounded in love, may have strength to comprehend with all the saints what is the breadth and length and height and depth, and to know the love of Christ that surpasses knowledge, that you may be filled with all the fullness of God. (Ephesians 3:14-19)

This Trinitarian address – to the Father, through the Son, in the Spirit – begins with an ascription to the Father alone, “from whom every fatherly household (patria) in heaven and earth is named” (my translation). The word patria, echoing the name Father (patēr), envisions the entire created order as an extended household polity (cf. Ephesians 2:19; Philippians 3:20). The Father is the Source and Head of every created order, of the heavenly ranks of angels and principalities and powers, and of all earthly institutions, sacred and secular. The cosmos is a divine patriarchy.

The priority of the Father is implicit in the early apostolic formula: “for us there is one God the Father, from whom are all things and for whom we exist, and one Lord Jesus Christ, through whom are all things and through whom we exist” (1 Corinthians 8:6). The ultimacy of the Father is also assumed in Paul’s end-time vision in which “when all things are subjected to [Christ], then the Son himself will also be subjected to him who put all things in subjection under him, that God may be all in all” (1 Corinthians 15:28).

While Paul may not have distinguished fully the “economic” or “immanent” relations of the Father and Son, he does assume a distinction of rank (taxis) between the two. Classic Trinitarian orthodoxy, East and West, maintained the monarchia (“primal source”) of the Father without lapsing into the “subordinationism” of Arius or Eunomius.

The second text comes from 1 Corinthians 11:3, which is probably another piece of apostolic catechesis (note Paul’s references to “tradition” and “custom” in 1 Corinthians 11:2 and 16). The issue at hand – women worshiping with heads uncovered – may seem marginal to us, but Paul “goes nuclear” on the matter by first appealing to the divine-human hierarchy: “I want you to understand that the head of every man is Christ, the head of a wife is her husband, and the head of Christ is God.” The logic of this hierarchy can be diagrammed thus:

| Relationship | Representative | Complement | Mystery |

| A: The head of every man is Christ | Christ (God-Man) | Man/male | Two natures of Christ – Second Adam |

| B: The head of the woman/wife is the man/husband | Male | Female | Sexual duality of the image of God |

| A: The head of Christ is God | Father | Son | Trinitarian relations |

The translation of kephalē (“head”) has proved a point of recent dispute, with some translating kephalē as “source” and others as “ruler” or “authority.” It seems to me kephalē has a semantic range that can include both. Given the discussion of “head”-coverings, Paul refers to the “head,” but he could equally have referred to archē, a near synonym with the senses of “beginning” and “authority.” With regard to the divine relations, the Father is head of the Son because He is the source or font of divinity.

Later in the passage, Paul makes this difficult statement: “For a man ought not to cover his head, since he is the image and glory of God, but woman is the glory of man” (verse 7). Paul here is interpreting Genesis 1:27: “So God created man (’adam) in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them.” I call this verse “difficult,” because for contemporary individualists, the idea of a corporate identity of husband and wife or of mankind in general is counter-cultural. (How long has it been since you addressed a Christmas card to “Mr. and Mrs. John Adams” or perused the once-famous photo collection The Family of Man?) The man or husband (the same word in Greek), Paul says, is the corporate image-bearer of the family or more widely of mankind. At the same time, Paul sees the woman is the image-bearer in another way: through conception and birth, thus filling the earth (verses 11-12; cf. Ephesians 5:21-31; 1 Timothy 2:12-15).

In this passage to the Corinthians Paul draws an analogy between the Triune relations and human relationships in the worshiping assembly. (He draws a related analogy with regard to husbands and wives in Ephesians 5:21-33.) To be sure, it is only a partial analogy. The Father and the Son are united in one nature, whereas believers are united with Christ by grace in the Spirit. By viewing the relationships of men and women in the Church in terms of the reciprocal character of the divine relations, we may come to see authority as not so much a matter of “command and control” as taking one’s place in a divine order, which is the proper definition of “sub-ordination.” And insofar as the Church is the Bride of Christ, men and women together respond to this order in the words of the “Magnifcat”: “Behold the handmaid of the Lord. Be it unto me according to your Word.”

Conclusion: Search the Scriptures

I need hardly say that I am venturing into a minefield of controversy in the wider culture where “the patriarchy” has been maligned as the font of all evils. Even in the Church, some women ask: “How can I be redeemed by a male Savior, who himself was victim of a Cosmic Abuser?”

It is likely Archbishop Welby faced such an atmosphere in London. According to the press release, he “was answering a question from the audience at St. Martin’s-in-the-Fields about what it means for him to call God his father, given his own complex personal experience of fathers, and being a father himself.” Given the nature and setting of that question, one might excuse the off-handedness of his reply. What troubles me is that Lambeth Palace put out the press release of his comments with no further comment or qualification.

Would this occasion not be a teaching moment for the senior Primate of the Church of England to search the Scriptures anew and explain the Creeds, which proclaim in the First Article: “We believe in God the Father Almighty…?

Now to him who is able to do far more abundantly than all that we ask or think, according to the power at work within us, to him be glory in the church and in Christ Jesus throughout all generations, forever and ever. Amen.

(Ephesians 3:20-21)

2 Advent 2018 – Scripture Sunday (Book of Common Prayer)