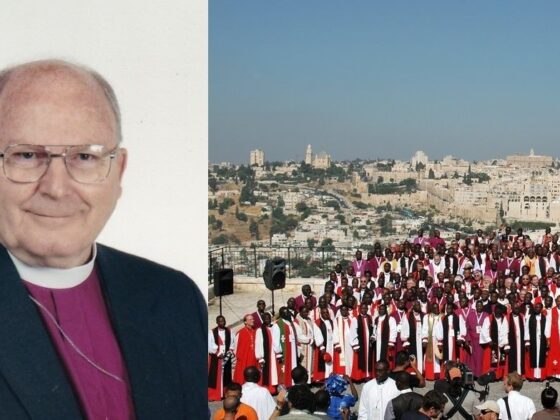

Presented at the Global Anglican Future Conference

21-26 October 2013

By Rev. Prof. Stephen Noll

“Glory to the Father and to the Son and to the Holy Spirit, as it was in the beginning, is now and ever shall be. Amen.”

We cannot begin to speak about the Person and work of the Holy Spirit without speaking of the Holy Trinity. The faith of our fathers, historic Christianity, is unequivocally Trinitarian. It was the particular vocation of the early Church to articulate the doctrine of the Holy Trinity, which is summarized in the Athanasian Creed:

Whosoever will be saved, before all things it is necessary that he hold the catholic faith… And the catholic faith is this: That we worship one God in Trinity, and Trinity in Unity; Neither confounding the persons nor dividing the substance. For there is one person of the Father, another of the Son, and another of the Holy Spirit.

As Evangelical Anglicans, we may ask: Is the doctrine of the Trinity and with it the Person of the Holy Spirit truly biblical? The answer of the early church and of the mainstream Reformation is unequivocally Yes. I would like to address this question in a bit more detail based on a plain and canonical-sense reading of the Old and New Testaments (see Jerusalem Declaration §2).

The primary witness of the Old Testament is to the oneness of God: “Hear, O Israel, the LORD is our God; the LORD is one” (Deuteronomy 6:4). Yet God’s unity is complex or diverse. There are many indications of relationality within the Godhead, as when God says: “Let us make man in our own image.” There are various manifestations of God, such as His Presence, His Glory, His Angel, His Wisdom and His Spirit. The Spirit of God can in some places seem to represent God Himself, as in the creation accounts when it says “the Spirit of God was moving over the deep” (Gen 1:2) and when God takes the clay and breathes into man’s nostrils the breath of life (Gen 2:7). In other places God’s Spirit seems almost an independent force, as when the Spirit of God “rushed on Saul” (1 Sam 10:10; 18:10-11). One of the most reliable signs of the Spirit’s presence is in the prophetic word (Isa 59:21); yet even here a “lying spirit” and false prophets can mislead a stubborn people (1 Kings 22:22; Ezekiel 13:9).

The Old Testament witness to God’s oneness is the foundation on which New Testament Trinitarian doctrine is built. It is a necessary bulwark against pagan idols, ancestral spirits in traditional societies, and even the fads of postmodern relativism. At the same time, as Karl Barth noted, God’s unity is not the religious glorification of the number one” (CD II/1), which is the foundational dogma of Islam.

The New Testament assumes the witness of the Old and builds on it, identifying the Lord God as the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. No Evangelist is clearer about this than St. John. He begins his Gospel by proclaiming that the Person of the Word by whom all things are made is with God and is God. This is the Word that became flesh in Jesus, the Son of God. At the same time, it is this very Son who reveals the Person of God the Father: “No one has ever seen God; the only-begotten God, who is in the bosom of the Father, he [the Son] has made him [the Father] known.” (John 1:18).

John is not speaking on his own authority, for it is Jesus Himself who boldly and repeatedly speaks of His Father, saying “I and the Father are one” and “I am in the Father and the Father in me.” In His Farewell Discourse, Jesus also testifies to the Person of the Holy Spirit, the “Paraclete,” a Greek word best translated “Advocate,” one who testifies on another’s behalf.

When the Advocate comes, whom I will send to you from the Father – the Spirit of truth who proceeds from the Father – he will testify about me. (John 15:26)

Jesus clearly identifies the Holy Spirit as a separate Person who proceeds from the Father and is sent by the Father and the Son and is “another advocate” alongside Jesus in and among believers.

There is another important Trinitarian relationship revealed in the Farewell Discourse: that of the Spirit and the Word. Jesus makes clear discourse that the Spirit testifies about His Person and he does so through Jesus’ words, his teaching, his commandments.

“If you love me, you will keep my commandments. And I will ask the Father, and he will give you another Helper, to be with you forever, even the Spirit of truth, whom the world cannot receive, because it neither sees him nor knows him. You know him, for he dwells with you and will be in you. (John 14:15-17)

The Spirit accomplishes this testimony retrospectively “reminding you of everything” (John 14:26), providing wisdom in the present and a prophetic hope for the future (John 16:13-14). It is this understanding of the Spirit’s work of inspiration of the apostolic testimony to the Gospel that makes it impossible to separate the authority of Christ from the authority of Scripture as God’s word written (2 Timothy 3:16; 2 Peter 1:21). This understanding likewise lays the foundation for the illuminating work of the Spirit within the believer and the rejection of any prophecy that is not focused on the Gospel of Jesus Christ (Revelation 22:18-19).

One can find a similar understanding of the Triune Person of the Holy Spirit throughout the New Testament, but suffice it to say that the Risen Lord Jesus himself commands his apostles to baptize in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit (Matt 28:18-20).

The Power of the Spirit

A prime characteristic of the Person of the Holy Spirit is power or, as it sometimes called, “effectual working” (Ephesians 3:7). Jesus Himself receives power through the Holy Spirit – at His baptism, in His earthly ministry, and at His Resurrection from the dead (Acts 10:38; Romans 1:4). Looking ahead to the Day of Pentecost, He asks his disciples to wait on the promise of the Father, “and you will receive power when the Holy Spirit comes on you; and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth”(Acts 1:8).

Waiting on the Spirit, both then and now, is essential because Pentecostal power involves God-inspired spontaneity. So at Pentecost the Spirit “suddenly” comes on the disciples as a mighty wind and they find themselves speaking in other languages. Speaking in tongues continued to serve as a sign of God’s in-breaking power, leading to faith in the case of Cornelius and his family. The abuse of this gift at Corinth involved a self-indulgent institutionalizing of the “confusion” of tongues in worship rather than seeking a fresh word in prophecy. True Pentecostal experiences of power have accompanied most revivals and mission breakthroughs, but it is equally true that many so-called Pentecostals have attempted to catch the Spirit in a bottle by claiming to reproduce the Acts of the Apostles on demand.

The power of the Spirit is manifested in three modes – if you will kindly let me continue adding “p’s.” The first is preaching. Spirit-filled preaching is inevitably evangelistic and expectant, as when Jesus gave the Great Commission with the assurance that “I am with you always,” through the Spirit. St. Paul describes his own mission preaching thus: “my speech and my message were not in plausible words of wisdom, but in demonstration of the Spirit and of power” (1Corinthians 2:4; cf. 1 Thessalonians 1:5). Spirit-filled preaching also involves teaching and exhortation of believers, as St. Jude puts it: “building yourselves up in your most holy faith and praying in the Holy Spirit” (Jude 20).

While it is true that the Spirit’s power in preaching derives from the truth of the Gospel, it is also the case that apostolic preaching was accompanied by signs, and these signs were most often the result of prayer. Hence Jesus’ disciples were to follow his example of healing the sick, raising the dead, cleansing lepers and casting out demons (Matthew 10:8). Jesus’ promise of the Spirit’s power in prayer – “ask and it will be given you” – is available to the whole Church and not some clerical elite; at the same time St. Paul recognizes extraordinary gifts of “faith” and healing distributed by the Spirit (1 Corinthians 12:9).

Finally, the Spirit’s power is not manifested primarily in explosive moments but is a process, which we call sanctification. The Spirit works in the daily context of our struggle with the world, the flesh and the devil. St. Paul urges Christians to put on the whole armor of God, “praying at all times in the Spirit, with all prayer and supplication… with all perseverance, making supplication for all the saints (Ephesians 6:18-19). The Spirit’s work in our lives is cruciform, as God’s power is made perfect in weakness (2 Corinthians 12:9; cf. Matthew 5:10; Revelation 6:9). It is a great error in some Pentecostal teaching to identify the Spirit’s working with worldly success. Rather, as the Jerusalem Declaration puts it: “We rejoice at the prospect of Jesus’ coming again in glory, and while we await this final event of history, we praise him for the way he builds up his church through his Spirit by miraculously changing lives.” It is changed lives, what John the Divine calls lives of martyria, martyrdom, not changed pocketbooks that mark the perfection of believers. And today, as much as any time in the Church’s history, many Christians are needing the Spirit’s strength to withstand the “fiery trial” that is coming upon them (1 Peter 4:12).

Participation in the Spirit

The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all. (2 Corinthians 13:14)

How often do we repeat this classic blessing without reflecting on that word “fellowship of the Holy Spirit”! The Greek word is koinonia, which can also be translated “participation” or “communion.” It is characteristic of the Third Person of the Holy Trinity that He is relational. Bishop John V. Taylor referred to Him as “the go-between God.” St. Augustine saw Him as expressing the love that unites the Persons of the Trinity. Contemporary scholar Robert Letham comments: “Communion and communication are inherent in his very being.”

This same love that unites the Persons of the Holy Trinity has now, as St. Paul says, “been shed abroad in our hearts through the Holy Spirit that has been given to us” (Romans 5:5). Regeneration, being born again or baptized in the Holy Spirit, is only possible based on the finished work of Jesus Christ. The Holy Spirit worked in the lives of men and women of faith in the Old Testament, but only occasionally. After Christ has come and died, risen and ascended, Father sends the Spirit through Christ to remain or abide with believers forever (John 14:16).

The coming of the Spirit now is not a temporary manifestation but a permanent indwelling, as Jesus makes clear: “In that day you will know that I am in my Father, and you in me, and I in you” (John 14:20). In this sense the Paraclete can also be called “the Comforter” because He brings continual assurance of the salvation once for all achieved in Christ’s work. Through the Spirit believers receive a foretaste of heaven; hence Paul blesses the church, saying “May the God of hope fill you with all joy and peace in believing, so that by the power of the Holy Spirit you may abound in hope (Romans 15:13).

The Spirit’s coming does not merely convey an inward sense of joy and peace. The believer manifests the Spirit outwardly to others by means of gifts and fruit (1 Corinthians 12:4; Galatians 5:22). These two words recall the sheer grace involved in the Spirit-filled life. It is not by works of righteousness or law but by grace working through faith that we please God (Ephesians 2:8).

The first fruit of the Spirit is love. God is, in his Triune being, love, as John so boldly puts it (1 John 4:8).

Beloved, let us love one another, for love is from God, and whoever loves has been born of God and knows God. Anyone who does not love does not know God, because God is love. In this the love of God was made manifest among us, that God sent his only Son into the world, so that we might live through him. In this is love, not that we have loved God but that he loved us and sent his Son to be the propitiation for our sins. Beloved, if God so loved us, we also ought to love one another. No one has ever seen God; if we love one another, God abides in us and his love is perfected in us (1 John 4:7-12)

For this reason, love is Jesus’ sole commandment and the supreme Christian virtue, above even faith and hope (1 Corinthians 13:13).

The fellowship of the Holy Spirit is naturally experienced in society, what Michael Nazir-Ali has called “the social dimension of the spiritual,” in the fellowship of the Church. “For in one Spirit we were all baptized into one body–Jews or Greeks, slaves or free–and all were made to drink of one Spirit” (1Corinthians 12:13). The apostolic fellowship includes common teaching, common prayer and sharing of earthly goods (Acts 2:42-44). The Holy Eucharist is a supreme sign of that fellowship, being a “participation in the Body and Blood of Christ.” While Anglicans may differ over the exact nature of Christ’s presence in the Eucharistic elements, they are agreed that they are spiritual food and drink to be received spiritually by faith and that they convey spiritual blessing and benefits.

The fellowship of the Holy Spirit in the Church has, finally, an historical and political shape. Jesus’ great final prayer is made on behalf of the worldwide Church of the ages:

I do not ask for these only, but also for those who will believe in me through their word, that they may all be one, just as you, Father, are in me, and I in you, that they also may be in us, so that the world may believe that you have sent me. The glory that you have given me I have given to them, that they may be one even as we are one, I in them and you in me, that they may become perfectly one, so that the world may know that you sent me and loved them even as you loved me. (John 17:20-23)

The desire for and task of Christian unity, of ecumenism, is therefore a work of the Holy Spirit. Too often Evangelical Christians have been quick to break fellowship over matters of “truth.” To be sure, the Holy Spirit is the Spirit of Truth, and the New Testament is filled with warnings of false teachers and false prophets (2 Peter 2:1-3; 1 John 4:1). Anglicans have over the centuries tended to be generous in maintaining ecclesial fellowship among those who disagree on “indifferent” matters of doctrine, discipline and worship. The Lambeth Quadrilateral recognizes that Anglican church order, while episcopal in form, can be “locally adapted” to different national and cultural settings. The Quadrilateral forms a basis for wider ecumenical dialogue, of which Anglicans have been leading participants over the past century.

The very term Anglican Communion suggests a fellowship of churches united in the one Spirit. For all its weaknesses, Anglicanism has historically presented a united witness to the Gospel around the globe and has been a major ecumenical dialogue partner with other traditions. It is therefore sadly ironic that the current crisis in Anglicanism has not only split the Communion but called into question the identity of the Communion to other Christian bodies.

The Holy Spirit is a spirit of love and of prophecy, as when the Exalted Lord says: “Hear what the Spirit says to the churches” (Revelation 2-3). The Statement of GAFCON 2008 makes clear that the reason 280 bishops and a thousand others met in Jerusalem was due to “the acceptance and promotion within the provinces of the Anglican Communion of a different ‘gospel’ (cf. Galatians 1:6-8) which is contrary to the apostolic gospel.” This statement was not made lightly; it resulted from a decade of controversy and inner-church politics in response to the unprecedented actions of the Episcopal Church USA and the Anglican Church of Canada (I have documented this unfortunate history in detail elsewhere). The breaking of communion between churches and bishops which has occurred over these past fifteen years is a great scar on Christ’s Body and source of grief to those of us who love our branch of the Church.

The goal of GAFCON is not to divide the church but to restore genuine communion in the Spirit. The Global Fellowship of Confessing Anglicans affirms the Lord’s ecumenical mandate, as is stated in the Jerusalem Declaration:

- We are committed to the unity of all those who know and love Christ and to building authentic ecumenical relationships. We recognise the orders and jurisdiction of those Anglicans who uphold orthodox faith and practice, and we encourage them to join us in this declaration.

- We celebrate the God-given diversity among us which enriches our global fellowship, and we acknowledge freedom in secondary matters. We pledge to work together to seek the mind of Christ on issues that divide us.

- We reject the authority of those churches and leaders who have denied the orthodox faith in word or deed. We pray for them and call on them to repent and return to the Lord.

I would argue that these statements reflect accurately the Biblical understanding of the fellowship between churches. There remain, for instance, significant obstacles to full communion with Rome and other historic Christian bodies. There are theological tensions within the “three streams” of the GAFCON movement itself. None of these churches, however, has taken a position so totally opposed to Scripture and unprecedented in the historic teaching of the Church as have the Episcopal Church and the Anglican Church of Canada.

Let me conclude with this question concerning the Holy Spirit and the GAFCON movement. In 2008, we stated: “GAFCON is not just a moment in time, but a movement in the Spirit.” What did we mean by that? Are we saying that the GFCA is a true communion of churches differentiating itself from the historic body from which we emerged. If so, then what further steps must we take to solidify that movement of the Spirit? If not, then what are we? I have addressed this issue in more detail in my essay “Sea Change in the Anglican Communion.” If we take seriously our belief in the Holy Spirit as constituting the fellowship of the church, we must in good conscience seek to discern His hand in directing our movement.

Discussion Questions

- In what sense is GAFCON a movement of the Spirit?

- What are the spiritual requirements for GFCA churches to “hear what the Spirit says to the churches”?