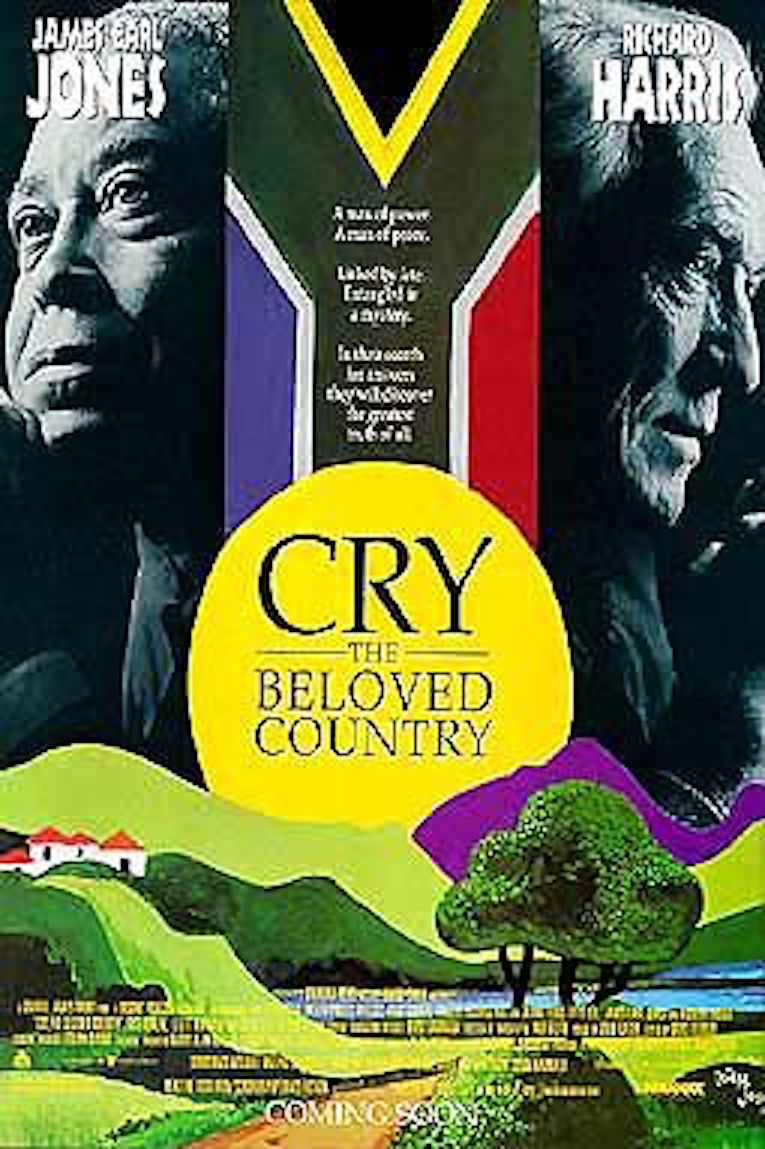

Available: DVD, Amazon Prime, Vudu, YouTube

Language: English, with some Zulu phrases (see below)

Characters:

- Rev. Stephen Kumalo (James Earl Jones) – an Anglican priest in Ndotsheni, a rural parish in Natal

- James Jarvis (Richard Harris) – a local white landowner in the same area, whose son Arthur is killed in Johannesburg

- John Kumalo (Charles Dutton) – Rev. Stephen’s brother and a union organizer in Johannesburg, who does not share his brother’s faith

- Rev. Theophilus Msimangu (Vusi Kunene) – a priest at an Anglican mission house

- Absalom Kumalo (Eric Miyeni) – Stephen Kumalo’s son, who leaves home for the city and is arrested for murdering Arthur Jarvis.

Sometimes the best way to get into a novel is by watching the film version. Alan Paton’s novel Cry, the Beloved Country was a classic half a century ago when I was growing up, often read in school or university, but I didn’t read it until after I saw the movie. In retrospect I have not been disappointed in either.

Alan Paton (1903-1988) was a white South African, whose liberal stances landed him in exile for a time. He was an Anglican, known for his short book Instrument of Thy Peace (1968). His Ah, But Your Land is Beautiful (1981) is a fictionalized history of the resistance movement to apartheid. Yet his first novel, Cry the Beloved Country (1948), made his fame up to the present.

The story is set in South Africa in 1946. Apartheid did not become an official doctrine there until 1948, but racialist policies had been in place for more than a century. Whites and blacks were “apart” geographically, socially and religiously, as portrayed by the two major characters of Cry, the Beloved Country, the Zulu priest Stephen Kumalo and the Anglo farmer James Jarvis. Both Kumalo and Jarvis live in the same rural region of Natal but are hardly aware of the other’s existence until forced to do so by a life-changing co-incidence: Kumalo’s son Absalom shoots Jarvis’s son Arthur in a Johannesburg robbery.

Ironically, Arthur Jarvis had become a crusader for justice for blacks, which his father finds incomprehensible. Absalom, unlike his rebellious biblical counterpart, is a simple soul who has been lured by friends into the robbery and fired the revolver in a panic. He is arrested and tried for murder, and Kumalo recognizes Jarvis at the trial. Soon thereafter, in a further coincidence, Kumalo meets Jarvis and falls down, visibly shaken. Then and only then Jarvis recognizes him:

J: I know you, umfundisi [pastor].

K: Umnumzana [Sir]

J: You are in fear of me, but I do not know what it is. You need not be in fear of me.

K: It is true, umnumzna. You do not know what it is.

J: I do not know, but I desire to know.

K: I doubt if I could tell it, umnumzana.

J: You must tell it, umfundizi. Is it heavy?

K: It is very heavy, umnumzna. It is the heaviest thing of all my years…. I am afraid, umnumzana.

J: I see you are afraid, umfundisi. It is that which I do not understand. I shall not be angry. There will be no anger in me against you.

K: Then, said the old man, this thing that is the heaviest thing of all my years is the heaviest thing of all your years also…. It was my son that killed your son.

The tragedy in the life of both these men unfolds in a tale of redemption and reconciliation.

There is a third player in the drama: Africa. Kumalo and Jarvis are both Africans, one Zulu, the other Anglo. Both are lovers of the soil and the beauty of the African hills and valleys. They are also both Christians, white and black.

The language of the script is lyrical, with a tone of polite simplicity, as seen in the excerpt above. The landscapes in the film are awesome, and the glimpses of African villagers are touching. In one scene, Rev. Kumalo is coming home after the trial, and he is greeted by a ululating chorus of women washing their clothes in the brook:. “Umfundizi, you have returned. Umfundizi, we give thanks for your return. Umfundizi, you have been too long away.”

The story feels like a biblical parable, and it seems the author intends it that way. Note the son’s name is Absalom, and both fathers are searching for their prodigal sons. At the same time, Stephen Kumalo is something of a saint and martyr, of whom it is said: “I have never seen a better man. If God loves him so much, why does he make him suffer?”

For all its rapturous beauty, a shadow of fear hovers over Cry, the Beloved Country. Paton himself stated that the book’s title came from this passage:

Cry the beloved country, for the unborn child that is the inheritor of our fear. Let him not love the earth too deeply. Let him not laugh too gladly when the water runs through his fingers, nor stand too silent when the setting sun makes red the veld with fire. Let him not be too moved when the birds of his land are singing, nor give too much of his heart to a mountain or a valley. For fear will rob him of all if he gives too much.

The fear he describes is not just a matter of racism, although forty-five years of apartheid were to follow the book’s publication (this movie was the first produced in post-apartheid South Africa). It is a fear that runs through the human heart, a fear that divides not just blacks and whites, but tribes and classes, and men and women (Gal. 3:28). It is a fear that ultimately can only be healed by the love of Christ (1 John 4:18).

Yet the movie and book also hold out hope for the future. Paton also wrote:

The book is a song of love for one’s far distant country. It is informed with longing for that land where they shall not hurt or destroy in all that holy mountain, for that unattainable and ineffable land where there shall be no more death, neither sorrow nor crying…”

As an American returning home from a sojourn in Africa, I sense the fear stalking this land. The days are dark, and I do not know how long the darkness will last. Cry the Beloved Country, the book and the film, offers us a glimpse of that glorious country, “the holy city, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband … by whose light we and the nations will walk (Rev 21:2, 24).