PALM SUNDAY: THE CROWN AND THE CROSS

Note: I preached this Palm Sunday 2001 sermon at Makerere University in Kampala shortly after we arrived in Uganda. The text is Luke 19:28-40.

The Palm Sunday Procession

Jerusalem is a city not unlike Kampala, built on a series of hills, with a steep valley running between them. Today in Jerusalem pilgrims will be marching across those hills, from the Mount of Olives to the East, carrying palm branches and crying Hosanna, a reminder of that first Palm Sunday when Jesus of Nazareth made his famous, or was it his infamous, entry into the city.

Jerusalem, the old city at least, was a walled city with gates. One of those gates facing East is called the Golden Gate. Indeed the stones of the wall do seem golden in the early morning sunlight. Today the gate is walled up, and no one can enter. Legend has it that the Messiah when he comes, will be the One who can open this gate. But in Jesus’ day, the gate was open, and it was to this gate that the figure on the donkey made his way that first Palm Sunday.

Onlookers on the Wall

I want you to imagine two men, one standing on the top of the city wall, a Pharisee, a follower of the Scriptures and God’s Law. Another man stands below him beside the gate. He is a Jewish tax collector, a publican. Until recently, he minded a local tax office. Then he had met one of his colleagues named Zacchaeus, a short little man, who had told him about the Teacher from Nazareth, who had performed miracles of healing wherever he went. He became a proselyte, a seeker of the Teacher.

These two men stand squinting in the morning light across that valley in Jerusalem, the Kidron Valley. Far across the opposite hillside, on the horizon, they catch sight of some figures moving like ants, then like a caravan of Eastern traders. They cannot really make out the figures in the caravan from that distance, but as it winds its way slowly down the opposite hill, there seems to be a small dust cloud accompanying it. The dust cloud gets larger and larger as it approaches, and then they can see that the dust is being stirred up by a crowd, a crowd of men and women. They are jogging along, reaching up and breaking off palm branches from the trees and then sweeping them through the air like politicians and their supporters here in the recent elections here in Uganda. As the palm fronds swoosh backward and forward, the motion churns up the dust from their feet, so that the whole procession looks like a miniature whirlwind on the move. On they come, down, down the opposite ridge, past the Garden of Gethsemane, into the depths of the Valley, still lost in shade, the Valley where King David had led his weary troops when he fled the city for fear of his rebel son Absalom.

The whirlwind disappears into shadows of the valley bottom for some minutes, and the Pharisee and the publican both strain their eyes but cannot see. However, they begin to hear faint sounds: shouting, singing, praising. Faintly, the words become distinct. Hosanna! God be praised. Hosanna. Blessed be the Name of the Lord. Hosanna. Blessed is the King who comes in the Name of the Lord! Then as suddenly as the little party had disappeared, it now reappears, the figures are more distinguishable and much greater in number when they last were seen. The crowd is growing as people begin running across stony paths from the surrounding villages in the valley. And people are now even running out through the gate of the city calling to each other. “Come, come. It is Jesus, the Master from Nazareth!’

The Publican and the Pharisee Greet Jesus

With that news the publican leaves his post at the gate and joins the frenzy. He is not a man versed in the Scriptures, but he does know that the days are coming when the Messiah will come and deliver his people Israel. Could this not be the birth pangs of the new age? The new David returning from Exile, gathering his forces to throw off the pagan yoke and to restore the kingdom to God’s ancient people Israel.

The Pharisee on the walls knows his Scriptures better. Finally, through the dust and commotion, he sees the cause of all the furor. There sits a man upon a donkey, riding slowly but steadily toward the city gate. “Yes, of course” he says to himself. The prophet Zechariah foretold this. Did he not say: Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion! Shout aloud, O daughter of Jerusalem! Lo, your king comes to you; triumphant and victorious is he, humble and riding on a donkey, on a colt the foal of a donkey?

The Pharisee, however, does not move from his perch on the city wall. He is not amused. What mockery! What hypocrisy! Who is this who pretends to fulfill prophecy? Who is this who stirs up the people with false hopes? Will the true Messiah not be accompanied by a host of heavenly warriors and the fire of God? How can these people chant: Peace in heaven and glory in the highest? There will be no peace on earth until the Law and the Temple are restored to their former glory. How will this happen through a motley crowd of unclean peasants throwing their cloaks on the ground and crying Hosanna, hosanna?

Finally, the Pharisee’s worst fears are confirmed. He can now make out the features of the rider on the donkey. He is not dressed like a priest. He is not dressed like a Levite. He is not wearing the proper tassels and amulets of a holy man. And he is certainly not dressed like a King. He has no scarlet robe, no battle mace, no crown. He is simply a Galilean, one of those rough-clad Northerners. The gall of such a man to imagine that he is fulfilling the prophecies. Does he not know that the Messiah is to be the Lion of the tribe of Judah!

By this time, the Pharisee has gotten worked up enough by this sight. He hitches up his robe and makes his way down the steps to the gate area, where the noisy crowd is now approaching. Hosanna! Hosanna! Blessed is the One who comes in the Name of the Lord. Thrusting himself forward, the Pharisee cries out to the figure on the donkey: Teacher, rebuke your disciples! Enough of this nonsense!

The procession halts. The rider signals silence to the crowd. Again, the Pharisee, now accompanied by a couple of his fellows, speaks loudly and sternly. Teacher, rebuke your disciples! The man on the donkey gazes at the Pharisee, with sadness in his face. For a moment he keeps silent. Then, looking at the large building blocks of the gate arch he replies: “I tell you, if these my followers were silent, these very stones would cry out.” He pauses for another moment, staring intently at the Pharisee. Then the procession and celebration moves on into the city.

I have dramatized a bit the story of Palm Sunday in order to get you to think about two ways of looking at Jesus. One of them is represented by the publican. He is full of enthusiasm, full of hope. He has come to know the power of Jesus. He has experienced or seen healing and miracles with his own eyes or through the testimony of others. No doubt you have met many people like him, the new convert. He can’t be repressed. He will give his testimony. He does not know much Bible but what little he knows he proclaims to the rooftops. He doesn’t sing in tune, but he makes up for it in decibels.

The Pharisee, on the other hand, is a member of the religious guild. No doubt he has a Ph.D. from a Western university and is chair of the religion department or the law faculty. He has a faith, to be sure, but it is a very calculating faith. He knows the Bible from long study, but this very knowledge hardens him toward the religious zealots of his day. He believes the Messiah will come some day, but he knows exactly what the Messiah will do: he will restore the religious folk like himself – the scribes and lawyers – to their rightful places of honour.

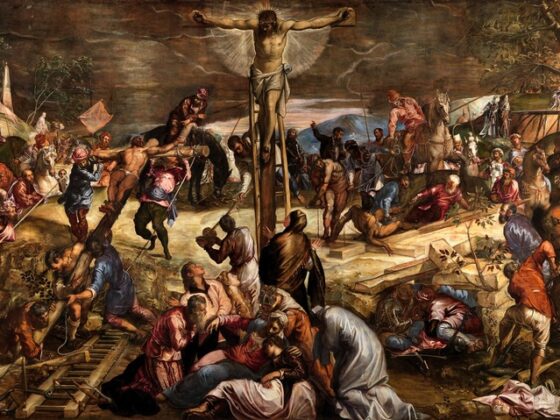

Now both the publican and the Pharisee, it seems to me, miss something important in the Palm Sunday event. One sees the crown without the cross; the other sees the cross without the crown. In a sense, they both look for the same thing: a conquering king, a victorious savior of the nation. The publican sees it in Jesus’ miraculous acts; the Pharisee rejects Jesus as unsuitable for the role.

Jesus Fulfills the Scripture

It is true that Jesus purposely chose to fulfill Scripture when he asked for the donkey to ride into Jerusalem. Surely he knew the prophecy from Zechariah. The prophet not only hails a king, a shepherd over God’s people, but he also predicts God’s dramatic entry into history, into the world. Then the LORD will appear over them, and his arrow go forth like lightning; the Lord GOD will sound the trumpet, and march forth in the whirlwinds of the south. He speaks of a battle against the Gentile nations but also their subsequent reconciliation to God: I will cut off the chariot from Ephraim and the war horse from Jerusalem; and the battle bow shall be cut off, and he shall command peace to the nations; his dominion shall be from sea to sea, and from the River to the ends of the earth.

He even speaks of God’s personal coming and a cosmic reordering of nature: On that day his feet shall stand on the Mount of Olives which lies before Jerusalem on the east; and the Mount of Olives shall be split in two from east to west by a very wide valley; so that one half of the Mount shall withdraw northward, and the other half southward. (Zechariah 14:4).

All these prophecies the Lord Jesus knew, far better than either the unlettered publican or the Law-abiding Pharisee. But Jesus saw even more deeply in the word another reality: that the Messiah’s crown of victory would also be a crown of death. He chose the king riding on a donkey as a symbol of royal character but also of royal weakness. David had not conquered by his own power, and when he had thought himself secure, rebellion arose from his own family. David was at his strongest when he was dressed in a linen tunic, dancing before the Ark of God. Zechariah had himself spoken this clearly: Not by might nor by power but by my Spirit, says the Lord.

So the true King of Israel was to be a man of humility, depending on God for his deliverance. This was the significance of Jesus riding the donkey. But Jesus saw even more deeply into the prophecy than this. Zechariah had also spoken of the messiah as a stricken shepherd, struck down by God Himself. “Awake, O sword, against my shepherd, against the man who stands next to me,” says the LORD of hosts. “Strike the shepherd, that the sheep may be scattered; I will turn my hand against the little ones. (Zechariah 13:7). This prophecy not only suggests that the Lord’s anointed will suffer but that his followers will suffer with him. By the end of Holy Week, this is exactly what happened.

I am convinced the Lord Jesus Christ knew exactly what he was doing when he rode into Jerusalem that first Palm Sunday. I believe he also knew what course God had laid out for him. He was to ride the Via Dolorosa, the Way of Sorrows, into the city on Palm Sunday just as surely as he was to walk it on Good Friday carrying a Cross.

But he was the only one to see this. The Pharisees, the religious elite, took offense that such a Galilean bumpkin would pretend to be the Messiah, the exalted king who was expected to enter in a victory procession rivaling the great spectacles in Rome. But his own disciples, like the publicans, likewise did not grasp that his healing power was directed toward a nobler purpose – the forgiveness of sins – and his miraculous power to the greater conquest – of death itself. And none of them saw that his triumphal entry was to be finally not through the Golden Gate but through the Gate of Death, not through the stone arches but through the fleshy portal of the human heart.

Pharisees and Publicans North and South

We Christians stand on the other side of the Resurrection. We know how the story turns out. But there is a sense in which we too, day by day, find ourselves in the place of the publican and the Pharisee. We ourselves can either be the enthusiast or the skeptic – or both at alternate moments. To be a true disciple, however, is to be neither of these but to take up our Cross and to follow on his royal road of service.

I come from a Church, the Episcopal Church in the United States, which is ruled by Pharisees. We experience the worst forms of hypocrisy: bishops who deny that Jesus is Son of God, clergy who would much prefer to lead someone to a bar or a brothel than to lead someone to Christ. Many of my colleagues, I am sad to say, love Palm Sunday processions in Church but will mount the pulpit to explain to their sheep that the whole thing is a myth. Fortunately, they do not have many sheep left listening to them, only the stone walls of their Gothic buildings. And who knows, maybe the day will come when those stone will cry out against them: Enough of this nonsense!

Here in Africa, I see there is a different situation. You are more like the publican, running out to greet Jesus. And I must make clear here, I prefer your lot. These were disciples, and Jesus did not despise their Hosannas. But he did know that many of these converts would turn on him again by the end of the week and cry “Crucify him!” or “I do not know the man.” And he knew that others would be scattered in grief, like the two disciples on the Road to Emmaus who said: “We had hoped that he would come to save Israel.”

In Africa and in many of the more Pentecostal churches in my country, we have a phenomenon called “happy-clappy” Christians. There is nothing wrong with being happy and nothing wrong with clapping for joy. But if that is all there is, then it is just as offensive to Christ as the sneer of the Pharisee. I was at a service a week ago, where the leader had a slip of the tongue (perhaps I should call it a slap of the tongue). “Let’s give Jesus a big slap,” he said. Well, that’s what you do if you clap on Sunday and then live like a heathen the rest of the week.

Taking Up the Cross

I was ordained as a minister almost thirty years ago. It was a joyous occasion, during the Easter season, in the spring of the year. The weather was beautiful, the church was beautiful, we had a wonderful party planned after the service. I had invited a clergy friend to preach. He surprised me by taking as his text the Palm Sunday lesson we heard today. “If you are to be a true minister of the Gospel,” he said, “you must accept that much of your ministry will be a time of sorrow and failure. You may enjoy this celebration, but do not forget that after the celebration comes the hardship.”

He was right. We have a spiritual song that goes “If you can’t bear the cross, then you can’t wear the crown.” That is the message of Palm Sunday. It is also a message which we need to learn every day if we wish to be effective ministers of Christ – lay or ordained. I shall be pursuing this theme of Being a Servant during our meditations every evening this week. May God touch you this week in a way that will change you for ever.

Collect for Palm Sunday

Almighty and everlasting God, in your tender love for us you sent your Son our Savior Jesus Christ to take upon himself our nature, and to suffer death upon the Cross, giving us the example of his great humility: Mercifully grant that we may walk in the way of his suffering, and come to share in his resurrection; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

Hymn for the Day: Theodulf (John Mason Neale), “All Glory, Laud and Honor“