Preface

I wrote this essay in 1998 for a projected anthology of articles on the Book of Common Prayer. The project never came to fruition. In the meantime, my wife and I served overseas for the next decade and during that time I became a priest in the Anglican Church in North America and had a small role in the production of its 2019 Book of Common Prayer.

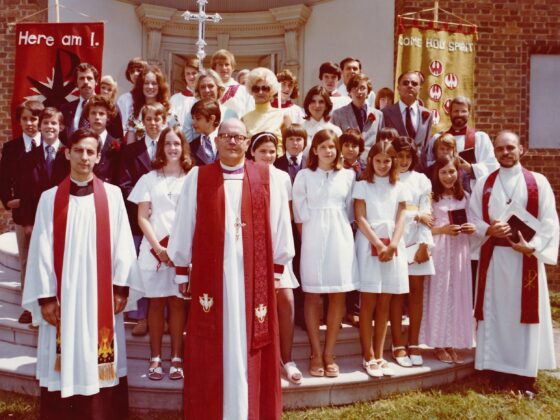

In 2021, I became an interim pastor to a church plant that was seeking to become a parish in the Anglican Diocese of Pittsburgh. Many of its members were young Evangelicals, graduates of nearby Christian colleges, who were new to the Prayer Book, and I began preparing them for a corporate confirmation service, with sermons on the Lord’s Prayer, the Ten Commandments, and the Apostles’ Creed. It was at this point that I dusted off this old essay. I have updated it with citations to the ACNA Prayer Book; however, much of the material will be relevant to other Anglican Prayer Books, ancient and modern.

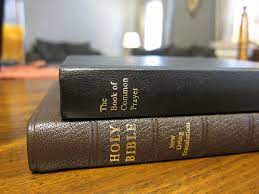

My goal is to sketch the many ways the Prayer Book and Bible conspire to deliver one message: the apostolic Gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ.

***

One day an Episcopalian who had worshiped faithfully in his church for many years happened to pick up a Bible for the first time (sadly, this is not an uncommon event and is not limited to Episcopalians). He was fascinated as he read through it to discover how much of its material had been lifted directly from the Book of Common Prayer!

This well-traveled anecdote speaks both to the biblical illiteracy of many Anglicans and to the intimate relationship between the Bible and the Prayer Book. The purpose of this essay is to show how Scripture and the Prayer Book can mutually inform and enrich the life of the believer.

Foundations

People today sometimes complain that the Prayer Book and the Bible are hard to understand. They think they have problems! Five hundred years ago, both Bible and Prayer Book (“missal”) were only available in Latin, and Latin was not any easier for ordinary people to learn then than now. The Reformation in England offered a dual gift: a Bible and Prayer Book in the language “understanded” of the people. This was a precious gift and not lightly achieved. The two great translators of the English Bible and Prayer Book, William Tyndale and Thomas Cranmer, paid for their work with their lives.

But which is more important, the Bible or the Prayer Book? The Anglican tradition has always answered this question unambiguously. The Bible alone is the primary authority (sola scriptura) for communicating the Gospel of Jesus Christ to God’s people. The modern revisions of the Book of Common Prayer place the lectionary, i.e., the table of Bible readings, at the end of the book as a matter of convenience, not of priority. The Bible is not an appendix to the Prayer Book; rather, it is the foundation on which the Prayer Book is based and by which it can be revised. So if someone is packing bags for a trip and has to choose between taking a Bible and taking the Prayer Book, the Anglican answer is: memorize the prayers and take the Bible with you.

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, the prime author of the Prayer Book, wrote that the purpose of the Prayer Book is to present “the very pure Word of God, the holy Scriptures, or that which is agreeable to the same; and that in such a Language and Order as is most easy and plain for the understanding of the Readers and Hearers.” Cranmer penned a “collect,” pronounced “collect,” which is a form of gathering prayer, intended to guide us as Bible readers.

Blessed Lord, who caused all holy Scriptures to be written for our learning: Grant us so to hear them, read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest them, that by patience and comfort of thy holy Word, we may embrace and ever hold fast the blessed hope of everlasting life, which you have given us in our Savior Jesus Christ; who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, world without end. Amen. Collect for the Second Sunday of Advent (BCP 2019, page 598)

This collect makes three overarching points taken from Scripture itself: that the Bible is inspired by God, that it is focused in salvation by Jesus Christ; and it is given for our growth in holiness (see 2 Peter 1:16-21; 1 Timothy 3:14-16). Every Anglican priest takes a vow that “I do believe the Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments to be the Word of God and to contain all things necessary for salvation.” In praying this collect, laypeople also pledge themselves to heed the Word in Scripture.

The Scripture collect lays out not only the origin and end of the Bible in God, but it speaks of several means by which believers can pray the Scriptures. The Bible is not a book dropped down from heaven to be placed on a pedestal or a coffee table. At the same time, it is God’s Word, for we do not make it true by what we choose to read and believe. Praying the Scriptures is a dialectical exercise in which the objective revelation in Scripture and the subjective work of the Holy Spirit in us leads to “something understood.”

The Scripture Collect and the Prayer Book as a whole can guide us in becoming better “people of the Book.”

Reading the Bible according to the Lectionary

The first step in praying the Scripture is reading. Jews and Christians are “people of the Book,” as Moses spells out.

“These words which I command you this day,” Moses says, “shall be upon your heart; and you shall teach them diligently to your children, and shall talk of them when you sit in your house, and when you walk by the way, and when you lie down, and when you rise. And you shall bind them as a sign upon your hand, and they shall be as frontlets between your eyes. And you shall write them on the doorposts of your house and on your gates.” (Deuteronomy 6:6-9)

Note here the centrality of the word, oral and written, attested to in the private home and the public square.

Another important principle of a religion of the Book comes when the books are collected in a canon, which sets the limits of the inspired word. For Jews the canon is limited to the “Hebrew Scriptures” or what we call the Old Testament. Christians added their own New Testament but differed among themselves over the size of the Old Testament. Protestants accepted the shorter Jewish canon, while Roman Catholics and Orthodox included the Apocrypha as Scripture. Anglicans follow the Protestant canon but retain some readings of the Apocrypha as helpful “as an example of life and instruction in manners.”

The Book of Common Prayer provides two cycles of readings, also called lessons or lections. The first is the cycle of Sunday lessons (pages 716-733) read in the “Ministry of the Word” section of the Holy Eucharist or alternatively in Morning Prayer when it is the principal service. The full order of Sunday lessons is: Old Testament, Psalm, Epistle, Gospel. A lay “lector” will normally read the first lessons, and the deacon or priest the Gospel lesson. Each lesson will be concluded with the acclamation and response, “The Word of the Lord” and “Thanks be to God,” and “The Gospel of the Lord” and “Praise to you, O Christ.” Often the lessons will be printed in the bulletin, projected on a screen, or available in a pew Bible. Given our poor listening skills in the West, worshipers may be wise to find a way to read along with the lector.

The Sunday lectionary is a three-year cycle, focusing on the synoptic Gospels: Matthew in Year A, Mark in Year B, and Luke in Year C (John’s Gospel and Acts are read in Lent and Easter but not in continuous order). This cycle also covers at least sections of all of the epistles. The Old Testament is much less fully represented, and since the Old Testament lesson is keyed to the theme of the Gospel text, the selection will jump about from week to week. For example, in Lent, lessons come from the Pentateuch (Genesis, Exodus, Deuteronomy), the Historical Books (Joshua, 1 Samuel, 2 Chronicles), and the Prophets (Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Joel).

Through the Sunday cycle of lessons, church-going Anglicans will hear most clearly the narrative of Jesus’ life, death and resurrection. They can also follow the epistles from week to week, especially if the preacher chooses to preach a sermon series on them. However, hearing the Bible on Sunday is not sufficient to form the kind of biblically-minded Christians that the Prayer Book presupposes.

The second cycle is used for the Daily Office, i.e., Morning and Evening Prayer. This lectionary (pages 734-763) is just as important as the Sunday cycle. The Daily Office may be used as a public liturgy on Sundays or weekdays, but it is normally intended for the home. It provides a daily reading from the Old Testament, epistle, and gospel, plus several psalms. Ideally, one should distribute these lessons between morning and evening, as was the practice in Israel (Psalm 92:2).

The Daily Office lectionary is arranged in a one- or two-year cycle. The readings are usually longer and more continuous than the Sunday cycle. Over two years, readers will cover each Gospel, Acts of the Apostles, and each of the Epistles twice, and major portions of the Old Testament once. There is also a selection of readings from the Apocrypha, which Anglicans consider profitable for reading but not inspired.

Praying the Daily Office full-strength, I should note, is a daunting regimen. The Prayer Book offers abbreviated services for “Family Prayer” (pages 66-78) and allows lessons to be shortened.

The Psalms occupy a special place of honor as the Prayer Book of the Bible. For this reason, the “Psalter” – in an updated revision of the “Coverdale” translation – is incorporated in the Prayer Book (pages 268-467), about 25% of the whole. No wonder the Episcopalian thought he had found the Bible in the Prayer Book! The two lectionaries offer readings from the psalms in every service. The Daily Office lectionary provides a one-month cycle of reading through the 150 psalms (page 735), with headings for Morning and Evening Prayer. Some people who may wish to pray the psalms more meditatively may choose to spread the readings over a longer period.

I think it is best not to think of the lectionary as the “law of the Medes and the Persians” but rather as a guide to use the whole Bible. In my view, clergy may be wise to follow the lectionary readings from Advent through Pentecost, which follow the narrative of Christ’s birth, ministry, suffering and exaltation, and turn to exposition of particular books of the Bible and biblical topics during the long Pentecost season.

Marking Scripture in the Sermon

When the collect speaks of “marking” scriptures, it literally refers to what any attentive reader might do with a pencil, taking notes. The best Bibles are dog-eared with marked-up margins, and many printed Bibles help out by providing cross-references at the center or bottom of each page. Thus when Jesus refers to David in Matthew 22:44, our notes should take us back to Psalm 110. Or when the patriarch Jacob says of his son Judah that “the ruler’s staff will not depart from between his feet until he comes to whom it belongs,” the notes will direct us to the Davidic Messiah and the Servant of the Lord (Numbers 24:17; Psalm 2:9; Isaiah 42:1).

Marking Scripture involves us in one of the most delicate yet important issues: the relationship of the Old and New Testaments. Jesus himself read from the Hebrew Bible and proclaimed that “today this Scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing” (Luke 4:22). Similarly, Peter, preaching about the coming of the Holy Spirit on the day of Pentecost explained: “This is what was spoken by the prophet Joel” (Acts 2:16).

Some Anglicans have been heard to say: “I don’t believe in the angry God of the Old Testament; I believe in the New Testament God of love.” There have been Christian teachers who believed this, e.g., Marcion in the second century, but this is a profoundly un-catholic and un-Anglican sentiment. The Articles of Religionplace a strong emphasis on the unity and harmony of the Scriptures: “the Old Testament is not contrary to the New; for in both Old and New Testament everlasting life is offered to Mankind by Christ” (Article 7). Therefore, they go on to say, “the Church has no authority to … so expound one place of Scripture, that it be repugnant to another” (Article 20).

Announcing the unity and harmony of Scripture is easier said than understood. How does one reconcile God’s ordering the destruction of the Amalekites with Jesus’ command to love your enemy? How does one move from the Psalmist’s complaint, “Rise up, O Lord! Why are you sleeping?” (Psalm44:23) to his conviction that “He will not let your foot be moved, and he who keeps you will not sleep” (Psalm 121:3)?

The reader using the Daily Office lectionary may not find the various lessons beg to be “marked”; usually one can read them along parallel tracks. Preachers who use the Sunday lectionary with its keyed lessons, however, are faced with this task week by week. Some may avoid the problem by choosing only one text to expound. But the lectionary challenges preachers to wrestle with the connection between texts.

The first Sunday of the Church year, Advent 1, Year A, provides the following lessons: Isaiah 2:1-5; Psalm 122; Romans 13:8-14; and Matthew 24:29-44. All of these lessons are “eschatological,” i.e., they speak of the ideal or the final state of God’s kingdom. But the tone is quite different. The two Old Testament lessons are rather happy. The Psalm portrays a self-sufficient Jerusalem, serving and delighting the tribes of Israel. Isaiah’s vision expands on this: at the end-time, the temple on Mount Zion will be exalted and will draw peoples from all nations to learn God’s law. The New Testament lessons, by contrast, are more ominous. Both emphasize the sudden coming of the end-time and the need for believers to be sober in behavior and expectant in faith. In both these lessons the focus has been transferred from Jerusalem and its temple to Jesus Christ. Paul urges his audience to “clothe themselves in the Lord Jesus Christ,” and Matthew reports Jesus promising His imminent return as the Son of Man.

So where will the preacher go with these texts? The Collect for Advent Sunday may suggest themes of the Second Coming of Jesus and the need for repentance. On the other hand, the whole Advent season is a time of recalling the role of the Old Testament prophets and John the Baptist in preparing the way for Christ’s first coming. A good lectionary sermon will not be handcuffed by conventional expectations (“You people should be ashamed to be buying Christmas trees during Advent!”). At the same time, it should seek to be guided by the Church year to see the continuities in Scripture regarding the coming of Christ.

At the beginning of Lent, one encounters three lessons that seem to clash. Both Old Testament lessons (Joel 2:1-2,12-17; Isaiah 58) call the people to “sackcloth and ashes.” By contrast, Jesus, in the Gospel lesson, explicitly contrasts the public fasting of the Pharisees with His disciples: “But when you fast, anoint your head and wash your face, that your fasting may not be seen by others but by your Father who is in secret. And your Father who sees in secret will reward you” (Matthew 6:17-18). The Protestant Reformers were so affected by the Gospel lesson that they abolished the traditional imposing of ashes, but the Prayer Book brings ashes back as an optional practice in the Ash Wednesday service (pages 542-545). It is the duty of the priest to explain a pastoral discipline of penitence that will include the concerns raised in the various lessons.

Learning the Gospel Story and the Rule of Faith

When the Scripture collect urges us to “learn” God’s word, it may intend something so simple as memorizing Bible verses. This is a venerable practice that we in our image-oriented culture find hard to do. But it is clearly worth the effort. The Christian liturgy is a kind of remembrance (anamnesis) of the mighty acts of God. But “declaring” those acts for oneself is essential for the completion of the remembering process (Psalm 145:4-6). One logical time to learn Scripture by heart is in times of meditation that are part of a daily “quiet time” (Psalm 19:14).

Learning Scripture also includes study. Jesus at one point describes the ideal disciple as a “scribe who has been trained for the kingdom of heaven” and His final “Great Commission” can be translated “Go, make learners” (Matthew 13:52; 28:19). One fruit of the scholarly research on the Bible in our day is the abundance of resources for those who want to understand the Bible. At the very least, one should possess a good “study Bible” that includes introductions and notes on the biblical text.

Learning Scripture involves more than head knowledge. The goal of the living, active word of God is to pierce our very being and life in all its parts (Hebrews 4:12). Scripture seeks to form our worldview so that we can, in a real sense, live out the Gospel story. This does not mean wearing sandals and playing “first-century Bible land,” but it does mean letting the Bible frame our outlook on ourselves and the world around us. The Book of Common Prayer is an excellent aid to this end, especially through its calendar and creeds.

The calendar of the Church Year (pages 687-715) can seem an impossibly complex system, and many Anglicans who follow it employ a “lesson calendar” to keep the dates and lessons straight. But putting such intricacies aside, the church year provides a rather straightforward re-enactment of the Gospel story.

- Advent is the “wrap-around” season. It recalls the Old Testament “preparation for the Gospel” among all those who were “waiting for the consolation of Israel” in Jesus’ first coming (advent). It also looks to the end of the story, reminding Christians that they too live by faith and hope that he will come again in glory.

- Christmas is the feast of the Incarnation, Jesus Christ the Word made flesh, one of the highest mysteries of the Gospel (John 1:1-18). The twelve-day season begins of course with his birth in Bethlehem, witnessed by lowly shepherds. It relates His circumcision as a Jew and God-given name Jesus (January 1). It also includes the feast days of St. Stephen the Martyr (December 26) and the “innocents” of Bethlehem slaughtered by Herod (December 28), which are sandwiched around the feast day of St. John, the Evangelist of light (1 John 1:5). Thus the joy and light of Christmas is seen as continuing to break into a dark and demonic world.

- The feast of Epiphany is an advance announcement of the mission of Christ to all nations, as represented by the visit of the magi. The Epiphany season focuses on Jesus’ baptism and ministry to the Jewish nation. The season concludes with the account of Jesus’ transfiguration, which gives a glimpse of His future role as cosmic Lord.

The Prayer Book provides a series of Special Liturgies of Lent and Holy Week (pages 542-595).

- Lent is the season that commemorates Jesus’ supreme ministry of the forgiveness of sins, as He overcame Satan in the wilderness and set His face to Jerusalem for the final test on the Cross. Ash Wednesday reminds us that we are the undeserving objects of His redemption, bound under the power of sin and death. Therefore fasting is the Lenten sign that growth in holiness comes only as we “walk the way of the Cross.”

- Holy Week itself encapsulates the Gospel. The four gospels devote nearly half their space to the “Passion” of Jesus Christ, His death on the Cross and burial in the tomb. The week begins with Palm Sunday (pages 553-558), on which the entire Passion narrative is read and in which we “enter with joy into the contemplation of those mighty acts whereby [God] has given us life and immortality.” It climaxes on Maundy Thursday (pages 559-563), where Jesus institutes the Lord’s Supper and washes the disciples’ feet (a foot-washing ritual is optional at this service). Good Friday is a fast day focused on the vicarious atonement of Christ, “whom God put forward as an expiation by His blood, to be received by faith” (Romans 3:25). The liturgy for this day (pages 564-577) includes “collects,” “reproaches,” and “anthems.” Many Anglicans prefer the traditional seven words from the Cross with solemn music. There is a brief liturgy for Holy Saturday as well.

- The Great Vigil of Easter (pages 582-595), new to Anglicans in the 1979 Prayer Book, includes a cycle of readings from the Old Testament indicating “that it was necessary that the Messiah should suffer and on the third day rise from the dead” (Luke 24:26,46). These lessons include the Creation, the Flood, Abraham’s sacrifice of Isaac, the Exodus at the Red Sea, and the prophets’ promises of a new Temple, a new covenant, a new heart, a new body, and a new Jerusalem. This recitation of salvation history is similar to the practice of Jews in the Passover ceremony recounting God’s saving acts at the Exodus. Many Anglicans prefer to welcome Easter Day with sunrise and morning services.

- The Easter Season runs from Easter Day, which commemorates the empty tomb and bodily resurrection of Jesus, to Ascension Day, when He ascended to reign at God’s right hand, and to the Day of Pentecost, when the Holy Spirit came upon the disciples. The primary tone of the Easter season is of victory, power, and joy in the Risen Christ and the Holy Spirit, and this is signaled by readings from John’s “spiritual” Gospel and the Acts of the Apostles. The refrain “Alleluia” signals that Christ’s work has completed the plan of salvation and inaugurated God’s kingdom for all time.

The calendar above occupies about half the year and is followed by up to twenty-nine “Sundays after Pentecost” with their “proper” collects and lessons. Think of the green color of vestments during this period as an opportunity for personal and corporate growth and vitality. In addition, the church year is interspersed by special “holy days” commemorating events in the life of Jesus, e.g. the Annunciation (March 25) and Transfiguration (August 6) and of celebrating apostles, saints, and martyrs mentioned in the Bible.

The Gospel story is recounted not only in the church calendar but in the Creeds. The Prayer Book includes three creeds. The Apostles’ Creed is the shortest and is found in the Daily Office and baptismal services. The Nicene Creed is usually recited in Holy Communion services (pages 109 and 127). The so-called “Athanasian” creed (pages 769-771) is not commonly used in worship.

The Creeds are a final form of what early Christians called “the Rule of Faith.” The Rule of Faith, while not itself biblical, claimed to be “proven” from Holy Scripture. What makes it different from Scripture itself is its doctrinal form. First of all, it is Trinitarian: thus it is appropriate that the first Sunday of the Pentecost season is Trinity Sunday, which is a celebration of the full revelation of the “God in Three Persons.” It may also seem appropriate to regard Trinity Sunday as the feast day of God the Father, Who is not otherwise recognized in the church year.

Another topic found in the Creeds is the confession of “one holy catholic and apostolic Church.” Like the non-linear time of the Church year, the life and growth of the church coincides with some of the normal activities of parish churches: Vacation Bible Schools and the beginning of Sunday School, stewardship campaigns, and mission trips. These activities, rightly ordered, are an integral part of the life fostered by the Prayer Book. The culminating feast of the Church is All Saints Day, which recognizes the many unseen and unknown lives of Christian believers and challenges all Church members to be “salt and light” in this dark world.

While Anglicans consider themselves “creedal Christians,” they less often note that they are “confessional Christians.” The “Ecumenical Creeds” of the first five centuries were focused on the nature of the Triune God and the Divine-Human nature of Jesus Christ. The 16th century Reformers received this inheritance of the early church; however, they addressed new issues which had arisen since that time. In particular, they claimed to recover St. Paul’s doctrine of justification by grace through faith. The Anglican version of these confessions is titled the “Articles of Religion,” or “The Thirty-nine Articles.” This confession has the same form and authority as the confessions of Lutheran and Reformed churches.

As Anglicanism became a global movement in the 19th century, it adopted the Lambeth Quadrilateral as a statement of “mere Anglicanism.” In the late 20th century, when the Anglican Communion was roiled by issues of human identity and sexuality, the Global Anglican Future Conference adopted the Jerusalem Declaration as a contemporary statement of the Faith.

All these doctrinal statements are found in the “Documentary Foundations” section of the Prayer Book (pages 766-802).

To “learn” the Scriptures with the Prayer Book as a tutor is to be formed both narratively and doctrinally. It is our challenge to integrate these two perspectives in our thinking, acting, and praying “so that the man of God may be complete, equipped for every good work” (2 Timothy 3:17).

Inwardly Digesting the Gospel in Word and Sacrament

The idea of digesting God’s word is deeply embedded in the Bible. The Psalmist exclaims, “How sweet are thy words to my taste, sweeter than honey to my mouth!” (Psalm 119:103). At the Exodus, the Israelites came to identify their hunger with their need for food, which God gave them supernaturally in the manna from heaven. So also Jesus said: “Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that proceeds from the mouth of God” (Matthew 4:4).

The Prayer Book provides discrete occasions in which the believer can ingest and digest God’s Word. The first is the sermon. The Prayer Book provides for a sermon or homily in all major services, and it is required at every Eucharist. The sermon follows the Scripture readings and frequently precedes the Creed. This order suggests that the word preached gains its authority from God’s inspired word in the Bible and its form from the Rule of Faith, which itself is drawn from Scripture.

For the Christian, God’s word has an in-breaking character, as when Paul says, “my speech and my message were not in plausible words of wisdom, but in demonstration of the Spirit and of power” (1 Corinthians 2:4). For this reason, preaching is not the same as lecturing; it is intended to change the hearer inwardly. It is the solemn responsibility of preachers to put on the mantle of a prophet and the shawl of a rabbi when they ascend the pulpit. The former role allows preachers considerable freedom in how they present the sermon; the latter role constrains them to derive their message from the text, whether the sermon be expository or topical.

Many preachers open their sermons with the prayer, “May the words of my mouth and the meditations of our hearts be always acceptable in thy sight, O Lord our Rock and our Redeemer.” This prayer alters slightly the first-person pronouns of its source (Psalm 19:14) in order to emphasize the dialectical character of the sermon. Having meditated on God’s word in preparing the sermon, the preacher now offers the fruit of that meditation as God’s Word to the congregation, and they are now called on to receive and ponder God’s word in their hearts. It has been customary in Anglican congregations for worshipers to pray silently before the service begins. One of those preparatory prayers might well be to “receive with meekness the implanted word, which is able to save your souls” (James 1:21).

Following the 1979 Prayer Book, the Anglican Church in North America accepted the principle that the Eucharist is the principal Sunday service (page 104). One of the great losses in this change, even if inadvertent, was the demotion of the sermon in many Anglican churches to a short meditation on the Gospel reading. Thus despite the fact that Anglicans hear a lot of Scripture read on Sunday, they often regard it merely as a prelude to the Eucharistic celebration. A diet of homilies, sadly, will produce undernourished Christians, since “sermonettes make Christianettes.” There is no reason liturgically that a Sunday service cannot include a full biblical sermon; it is simply a matter of priest’s and people’s time priorities.

The second way in which God’s word is taken in is through the sacraments. The English Reformers often spoke of the sacraments as “visible words,” and they restricted the term sacrament (Greek “mystery”) to those rites that had been specifically ordained by Jesus in the Bible and that proclaimed the fullness of His saving work (hence “the Gospel sacraments”). They also insisted that the key moment of the sacramental act involves a biblical phrase. In baptism, it is “I baptize you in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit” (Matthew 28:19). At the Eucharist, it is Jesus’ words of institution, taken from the Gospels and St. Paul.

The Eucharist service itself is divided into the ministry of the Word and the ministry of the Table. Often clergy move from the lectern/pulpit area to the chancel at the Offertory to signify this division. The substance of the Gospel conveyed in these two moments is not different, only the mode of proclamation and the manner of reception. The Eucharistic action itself, the re-enactment of the Last Supper and the anticipation of the heavenly banquet, are a kind of proclamation, as St. Paul himself noted: “For as often as you eat this bread and drink this cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes” (1 Corinthians 11:26).

The sacrament, like the good sermon, presents Christ and His grace to be received by faith, although the mode of receiving Christ and His saving work in the Eucharist is no longer by ear but by mouth. As Jesus himself said, “For my flesh is food indeed, and my blood is drink indeed. He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me, and I in him” (John 6:55). And the Holy Spirit that inspires the written word is also active in the sacrament, which is “given, taken, and eaten, in the Supper, only after a heavenly and spiritual manner.”

The final way in which we digest God’s word is through the biblical prayer. Biblical prayer suggests a certain attitude to receiving, meditating, and offering back God’s word in Scripture. The German pastor and martyr Dietrich Bonhoeffer described it this way: “God’s speech in Jesus Christ meets us in the Holy Scriptures. If we wish to pray with confidence and gladness, then the words of Holy Scripture will have to be the solid basis of our prayer.”

The Prayer Book offers us two major resources for biblical prayer. The first is the Psalter. The Psalter takes up 225 pages, or about 25% of the Prayer Book, and the lectionary assigns psalms for every service. In doing so, it stands in a long tradition of Christian use of the Book of Psalms, dating from the New Testament to the present. Until the 19th century, Anglicans had no hymnal but used only sung psalmody. To be sure, the Psalms belong to the Old Testament and do not speak explicitly of the Gospel of Jesus Christ. But from early on, Christians understood the psalms not only to be the prayers of David but also to embody the very prayers of Christ. Bonhoeffer asks: “Who prays the Psalms?” and answers:

David (Solomon, Asaph, etc.) prays, Christ prays, we pray. We – that is, first of all the entire community in which alone the vast richness of the Psalter can be prayed, but also finally every individual insofar as he participates in Christ and his community and prays their prayer.

Thus the Psalter becomes the pre-eminent vehicle for biblical prayer within the Prayer Book.

Secondly, the Collects offer a second-order example of biblical prayer. Like the Psalms, the collects of the Church occupy considerable space (pages 598-640). Each Sunday and feast day in the church year has its own collect or collects. In addition to these seasonal collects, there are magnificent collects in the liturgy like the Collect for Purity (page 323, 355). They are not, of course, Scripture itself, but they represent the Church’s centuries-long meditation on the biblical Gospel. Let us take, for example the first collect for Advent (page 159, 211) with its obvious biblical references:

Almighty God, give us grace to cast away the works of darkness [Romans 13:12] and put on the armor of light [Romans 8:12; Ephesians 5:11], now in the time of this mortal life [Romans 8:11; 2 Corinthians 4:11] in which your Son Jesus Christ came to visit us in great humility [Philippians 2:3,8]; that in the last day, when he shall come again in his glorious majesty to judge both the living and the dead [Matthew 25:31-32], we may rise to the life immortal [1 Corinthians 15:53-54]; through him who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen.

While we normally experience the Collects as part of the public liturgy, they are appropriate for the Daily Office throughout the week and form a fine complement with the assigned psalms. In addition to the Collects, the Prayer Book offers a variety of prayers, litanies and thanksgivings for occasions in the life of the Church.

One common objection to Anglican prayer made by members of charismatic and independent churches is that “said prayers” are inherently rigid and mechanical, lacking spontaneity and the freedom of the Spirit. This has often been true of some Anglicans, such as the pastor whose tombstone praised him for having “preached the Gospel for forty years without enthusiasm.” Recent Prayer Books have rightly allowed more “free space” for personal intercessions. But it is equally true that much spontaneous prayer and praise is just as dull as said prayers and often is more about the pray-er than about God and His Word. Hence, for many Anglicans today, “blended” worship and music has become the norm.

The richness of Prayer Book worship comes from its rootedness in Scripture and its seasoning by the long history of Christian spirituality. It speaks not only to all “sorts and conditions of men” but to all sorts and conditions of the human soul. The great English poet George Herbert has captured the essence of the Anglican attitude toward Scripture:

O Book! infinite sweetness! let my heart

Suck every letter, and a honey gain,

Precious for any grief in any part;

To clear the breast, to mollify all pain.

Thou art all health, health thriving, till it make

A full eternity: thou art a mass

Of strange delights, where we may wish and take.

If we use the Prayer Book as it is intended to “read, mark, learn, and digest” God’s Word, we shall find it a fit companion with Scripture along the way until we attain the blessed hope of everlasting life given us in our Savior Jesus Christ.