Day Eleven

Note: For anyone joining this series in Week 3 (you can find the consolidated Week 1 here and Week 2 here, we are continuing the verse-by-verse exposition of George Herbert’s sonnet “Prayer” assisted by the fine book by Dennis Lennon, Turning the Diamond: Exploring George Herbert’s Images of Prayer.

Here is the sonnet in full.

Prayer the Church’s banquet, angels’ age,

God’s breath in man returning to his birth,

The soul in paraphrase, heart in pilgrimage,

The Christian plummet sounding heaven and earth;

Engine against the Almighty, sinner’s tower,

Reversed thunder, Christ-side-piercing spear,

The six-days world transposing in an hour,

A kind of tune, which all things hear and fear;

Softness, and peace, and joy, and love, and bliss,

Exalted manna, gladness of the best,

Heaven in ordinary, man well drest,

The Milky Way, the bird of Paradise,

Church-bells beyond the stars heard, the soul’s blood,

The land of spices; something understood.

The second stanza, or so it seems to me, begins with warfare, contention, even against God Himself, and ends with irresistible tunefulness, something Adam and Eve rejoiced to hear in Eden (“the world, so great, so wunderbar, is Thy handiwork”). In the third stanza we travel on the wings of prayer upward and outward on a mystical cloud of softness and bliss into the heavenly realms, somewhat like Ransom’s journey to Venus in C.S. Lewis’s Perelandra.

Yet there is always something very down-to-earth about this journey. So commenting on “heavenly manna,” Dennis Lennon starts us at a mythical Jewish restaurant:

When next you dine at your favorite Israeli restaurant, try the manna. You might reflect on its significance to the prophetic mind, and how George Herbert could ever utter “manna” in the same breath as “gladness of the best.”

[From the menu]:

A sweet sticky substance produced by a number of insects that suck the tender twigs of tamarisk bushes in the desert region of Sinai. The “honeydew excretion” falls to the ground where in the hot desert air, the drops quickly evaporate, leaving a solid residue… early risers can gather the substance for food.

The surprise of linking manna in prayer is cushioned if instead of original, “neat” manna, the chef has served a confection known as “manna from heaven”:

It is made by dissolving the “honeydew excretion” in hot water, straining out the bits of twigs and insects, then cooking it into a thick porridge and adding chopped almonds… a pudding made with the manna cooked to a soft cream…

Almonds and cream indeed! Not according to the Exodus account of Israel’s trek through the desert (Exodus 16:11-16). Yet the psalmist called manna “the grain of heaven…bread of angels” (Psalm 78:24,25). Far from being a wayside snack to keep Israel fueled on her journey to Canaan, the whole purpose of the journey was to bring the people to the manna! (Deuteronomy 8:2-3). So the great forty-year wilderness trek was one long lesson in practical trust….

Apparently God reckoned it was worth every minute of those forty years to wean Israel (she was the representative human family) off the deadly fantasy of life “by bread alone.” [SN: Cue online coronavirus sermon.] He initiates the crisis. With the goodies of Egypt far behind them, and the relative security and prosperity of Canaan a long way ahead of them, he takes Israel into the laboratory of the wilderness. There, away from the shops, the stock market, and the cinemas; away from theoretical classroom religion, life focuses down to a terrible simplicity: can God be trusted with our lives? Is the Lord among us or not! (Exodus 17:7).

Manna is the strange food of God encountered by people on the move in response to his word. It is, says George Herbert, not manna-on-the-ground, under those tamarisk bushes at Sinai, but “Exalted Manna,” for it is the life, grace and power of our risen and ascended Lord Jesus Christ.

Prayer is a Bedouin who traverses the wilderness in obedience to God’s word, looking to Christ, our exalted manna, for sustenance. Prayer is our response to those moments of crisis, the danger that we might live by bread alone and the opportunity to choose to live instead by God’s word. By prayer we open up the crisis to Christ’s power and love, in total honesty about our fears and confusions and all the “what ifs” raised by the crisis. By prayer the exalted manna passes into our bodies, hearts and minds and amazingly we find ourselves going joyfully with our Lord.

Curiously, Dennis Lennon does not examine carefully the second part of the verse “gladness of the best,” which strikes me as strangely, at best, connected to “exalted manna.”

“Gladness” is a tricky word; it can suggest superficiality – “so glad to see you” – or even hypocrisy, as in “glad-handing.” The Bible has no one word for it, but I think “cheerfulness” comes closest. Forget about the stewardship sermon: “God loves a hilarious giver” (2 Corinthians 9:7). Good cheer does not so much guffaw as smile. Gladness looks smilingly for “the best.”

When I think of “gladness of the best,” I think of my wife Peggy. In our family photos over the years, the whole brood may be scowling, or looking at the ground, or offering forced smiles for the camera – all but one, who smiles naturally. When I met her in our mid-teens, I, premature skeptic that I was, was intrigued: I don’t know what makes this girl tick, but whatever it is, I want it, I mean I want her, for myself. And by God’s prevenient grace, she saw the best in me. Peggy’s natural gift has seasoned over the years, and in her prayers, but much is the same: “You always see the good in people,” one friend recently commented.

Many of us pray regularly for “problem people,” for “hard nuts to crack” in our family or acquaintance. It is hard not to become wizened like Israel in the desert: “What, manna again today!” “Gladness of the best” does not give up, indeed greets each such prayer with cheer. Like love, gladness “bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things” (1 Corinthians 13:7).

One might extend this gladness outward to the world more generally. Paul concludes his advice to the Philippians with this: “Finally, brothers, whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is commendable, if there is any excellence, if there is anything worthy of praise, think about these things” (Philippians 4:8).

So maybe “gladness of the best” is the point of living by exalted manna alone. George Herbert captures this glad spirit in his poem on “Gratefulness,” not surprisingly one of my wife’s favorites:

Thou who hast given so much to me

Give me one more thing, a grateful heart….

Not thankful, when it pleaseth me;

As if thy blessings had spare days:

But such a heart, whose pulse may be

Thy praise.

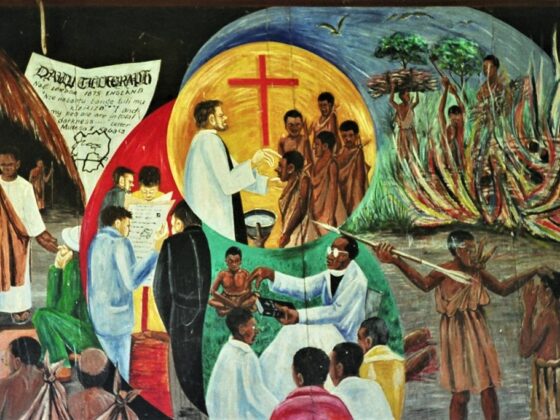

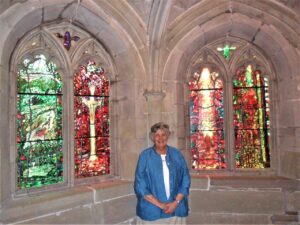

Photo: Peggy Noll in front of Thomas Traherne windows in Hereford Cathedral.

Day Twelve

Softness, and peace, and joy, and love, and bliss,

Exalted manna, gladness of the best,

Heaven in ordinary, man well drest,

The Milky Way, the bird of Paradise,

Blogging in my retirement, I’ve enrolled in the ranks of the pajama media myself. But from years in Africa, I would agree on the importance of dressing “smart.”

Dennis Lennon continues:

No one gets out of bed well dressed. As my wife explains to me frequently, a smart appearance doesn’t simply arrive with the morning post…. So when George Herbert says that prayer is “man well dressed,” I am inclined to think he means the necessary prayer before prayer, preparation for prayer; the act of praying oneself into prayer. Who of us would question the need for it. Left to ourselves, isn’t it true that most of us are spiritually asleep most of the time?…

Experience and experiment over the years evolves strategies for entering into prayer. Some folk claim their inner world first thing in the day by reading a psalm or meditating on a set daily passage of scripture. Others, I am assured, sing or listen to spirit-warming music, they may contemplate a picture or an icon or a candle flame. We each must find our own way and having done so share our findings with one another….

Although we may come to God “well-dressed” in prayer that of itself can never be grounds of our confidence. Herbert’s apparently quaint and homely metaphor is a ticking time bomb when it sinks into our understanding and explodes its meaning. We dress up, and are met by the God who dresses down: prayer is “heaven in ordinary, man well dressed.” A couple weeks ago I witnessed a nice illustration of what Herbert is saying.

The Queen visited our small town. I have a couple photos of the occasion… In them the people are smiling, the policewoman is smart and watchful; the mayor looks satisfied if slightly burdened, a group of Morris dancers are clearly in top form. But it’s the children I am most intrigued by. I wonder what they made of the occasion? Were they a shade disappointed? I ask this because although the market place was thoroughly well-dressed for the visit, the Queen arrived “in ordinary.” She looked like anyone’s grandmother, dressed in neat “sensible” clothes for enjoying a day out among friends with a decent lunch not far-off. Not a tiara to be seen, no glitter, no great coach or Household Cavalary to haul local rowdies off to the Tower. You could almost hear the four-year-olds muttering to each other “Is that it?”

When town “well dressed” encountered Queen “in ordinary” it made for a relaxed, happy, informal day. The dazzle of majesty didn’t get in the way of real meeting. “Man well dressed” is nothing more than our duty, the respect we owe to our creator; “heaven in ordinary” is all grace and love and divine self-emptying. Our confidence, joy and peace in meeting with God is held in the phrase “heaven in ordinary” and in the answer to the question, “How ordinary is God’s ordinary?”

As ordinary as the incarnation of our Lord Jesus, who “made himself nothing, taking the very nature of a servant” (Philippians 2:7). The splendour of his majesty was not allowed to distance him from us; he came as close to us as one of us. The God, who in his blazing holiness is a terrifying prospect for sinful people, has done the unthinkable. He has crossed over to our side in Christ. Not merely in a symbolical gesture but in utterly real identification and solidarity with us. Now he stands among his people, “in ordinary,” extending all the achievement of his life, death and resurrection to cover and to include us. He is our saving brother “Jesus” (Hebrews 2:10-18). How “ordinary”? He clothed himself with the reality of our flesh and all its weakness, then redeemed it, us and all mankind from within our flesh. As the Church Fathers delighted to proclaim, “what Christ did not assume he could not heal.” He assumed, took on to himself, all of our nature and flesh (“in ordinary”) in order to heal it, us, completely from within.

Just ponder what Christ’s “in ordinary” means as we approach him “well dressed” in prayer. He, God, is as near to us as our own nature, as the breath in our bodies. There is no gap between God and us. To close the gap for ever, God in Christ clothed himself with our nature; we clothe ourselves with his nature as children of God. We are “in Christ” and Christ is “in me.” We could explore this astonishing truth for the remainder of the book; instead we will allow George Herbert to summarize it in what I find to be his most profound poem, “Aaron.”

Let me add this comment before I quote from “Aaron.” I have had a custom of sending a xeroxed copy of this poem to students and colleagues who are being ordained to the priesthood – for an obvious reason as you read it.

One major change, however, from the first high priest is that the “country parson” was dressed in ordinary black, identifying himself with the lowliest people of his parish. And he instructed them in word and life to share with him in the “royal priesthood” of Jesus Christ (1 Peter 2:9).

If you compare “Aaron” with “Love III,” you will see the same V-shaped pattern of movement from our creation and sin to Christ’s incarnation, redemption, and invitation to rise and sit with him at table throne (for a similar double-V shaped poem, see “Easter Wings”).

Aaron

Holiness on the head,

Light and perfections on the breast,

Harmonious bells below, raising the dead

To lead them unto life and rest.

Thus are true Aarons drest.

Profaneness in my head,

Defects and darkness in my breast,

A noise of passions ringing me for dead

Unto a place where is no rest.

Poor priest thus am I drest.

Only another head

I have, another heart and breast,

Another music, making live not dead,

Without whom I could have no rest:

In him I am well drest.

Christ is my only head,

My alone only heart and breast,

My only music, striking me even dead;

That to the old man I may rest,

And be in him new drest.

So holy in my head,

Perfect and light in my dear breast,

My doctrine tuned by Christ, (who is not dead,

But lives in me while I do rest)

Come people Aaron’s drest.

Photo: George Herbert window at St. Andrew’s Church, Bemerton.

Day Thirteen

Softness, and peace, and joy, and love, and bliss,

Exalted manna, gladness of the best,

Heaven in ordinary, man well drest,

The Milky Way, the bird of Paradise,

Dennis Lennon continues:

Approaching the full circle of Herbert’s diamond as we turn it in the light, his “inspired litany, this zodiac of marvels,” we meet images of “near hallucinogenic intensity.” But the author isn’t simply handing around mystical cannabis when he describes prayer under the ravishing metaphors of “the Milky Way, the bird of Paradise.” Those are ecstatic images – but Christian ecstasy is never a flight from reality, rather the opposite. Like the shimmering and radiant effect of bright sunlight on water, Christian ecstasy arises out of our being “in Christ” who is the Lord of all reality. Movement into Christ is movement into reality.

Christ indwells his people, who indwell him by the Holy Spirit. It is a relationship which places us in vital connection with the One who even at this moment is speaking all creation into being and holding it in life (Hebrews 1:1-4; Colossians 1:15-20). We are thereby mysteriously but truly related to “All things,” they are our rightful sphere by virtue of our union with Christ their Lord. An incredible statement of our status in Christ runs:

All things are yours, whether Paul or Apollos or Cephas or the world or life or death or the present or the future – all are yours, and you are of Christ, and Christ is of God. (1 Corinthians 3:21-23)

One thing is made crystal clear b those words: no longer can we conceive of “in Christ and Christ in me” as a purely internalized, privatized affair concerned mainly, if not exclusively, with our own inner world. If Christ the Lord of “All things” dwells in you and you in him, then you have dealings and connections with everything else. Therefore no sooner has George Herbert satisfied us concerning the nearness of Christ, and prayer as the language of personal intimacy with him (“Heaven in ordinary…”) than he sends us rocketing out to the boundaries of our estate, “All things … the world…” Except he suggests those farthest limits not by equations or formulae, but in two utterly beautiful things located way out there in the distance.

Prayer as reaching up into the immensities of space is symbolized by the lovely, hazy, stream of rich star-fields flowing through Cassiopeia and across Orion, which we call the Milky Way. And to indicate the boundaries where knowledge emerges from mystery and discovery takes over from hiddenness, Herbert evokes a creature of mythic elusiveness and beauty – for a seventeenth-century Englishman located on Salisbury Plain – from the jungles of the strange and fascinating East: the bird of Paradise….

It seems therefore that prayer as a star galaxy and as an exotic bird is a beguiling way of claiming “All things … the world …” as the domain of prayer and worship. It is saying that everything that exists should be raised up to God in thanksgiving for his glory….

A friend once told me that when he gave thanks for his food in a restaurant he extended his silent prayer to include everyone in the place: as their brother, and on their behalf, just in case God should go unthanked for his gift! He had hit upon a profound aspect, perhaps the central one, of a Christian’s function within a largely unbelieving society….

We are suggesting that prayer as “the Milky Way, the bird of Paradise” will open up our interests and prayers to take in all life. This is the wisdom and subversive power of “diaspora” life. Christians are scattered all over society, yet placed there by God for his purposes: cells at prayer and worship, claiming the neighborhood for God’s transfiguring blessing.

You have long discovered how compressed and concentrated Herbert’s apparently simple images are. It is necessary to “move in” with his metaphors before they yield their content. So I ask: why these two unusual things, the galaxy of stars and the exotic bird? Did Herbert smile to himself when he saw them side by side on the paper in front of him? I hope so, for they make me smile every time I read them. And I am sure they make children smile. “The Milky Way – what luck! To think that someone had the good sense to name the 100,000 million stars of our galaxy after a chocolate bar! And who thought to call that magical bird after “Paradise” (meanings within meanings, within meanings)?

What has Herbert hidden for us within the two images? Both are stunning in their exotic and elusive beauty. They suggest prayer as a looking to the God of indescribable and holy loveliness, the fount of all joy and love and delight.

Reading Lennon’s comments on the Milky Way reminded me of one other witness who brought me to Christ. For two years, I attended an odd little junior college located in the high desert of eastern California. The college was enclosed on all sides by the White and Inyo Mountains, and at night we would take long walks down the only paved road there and look up at the Milky Way. Seen from 5,000 feet up, far from the smog of LA, the stars came down and kissed the crest of the mountains. I was not a Christian at the time, but I was not without questions and God was not without witness: “The heavens are telling the glory of God…”

And a second thought half a century back came to me. When I was in seminary, this time in Berkeley, California, I went to a healing conference where Agnes Sanford spoke. She was one of the great prayer warriors in the church, and I remember her saying that she prayed every day for the San Andreas fault. Well, Agnes Sanford has gone to be with the Lord, but the San Andreas fault has not yet slipped. Perhaps someone took up her calling, or perhaps she is still praying.

Photo: Deep Springs Valley, California.

Day Fourteen

Church-bells beyond the stars heard, the soul’s blood,

The land of spices; something understood.

Let’s start with a brief primer on the sonnet. Of the two main forms – Petrarchan/Italian and Shakespearean/English, Herbert follows the latter, that is, three quatrains (abab cdcd efef) and a couplet (gg). Like all great poets, he exercises freedom within the form, e.g., the third quatrain is “e-f-f-e.” More importantly, “Prayer” does not flow but is chopped up into 27 metaphors and many half-lines, some of which are thematically connected, e.g, “heaven in ordinary, man well drest” and others are conundrums, e.g. “reversed thunder, Christ-side-piercing spear.”

The final couplet usually provides a conclusion or moral to the previous stanzas. Yet once again, Herbert plays a trick on us (more on that in tomorrow’s post).

So with that little lesson, let’s return to the penultimate verse and Lennon’s commentary:

So, prayer is said to be like “church bells beyond the stars heard” which at first glance suggests that when the bells of Herbert’s church. St. Andrew’s Bemerton, rang their call to worship the inhabitants of heaven took notice… Well, it would be disappointing to come all that way to be told something so unremarkable….

It is not our church-bells that are heard “beyond the stars,” but heaven’s bells that are heard among us here in our world. Humbling though the thought is for people like ourselves who assume that nothing of worth happens unless we initiate it, the first call to prayer emanates from heaven. Our prayer-bells answer theirs “on earth as it is in heaven.” Our churches are like echo chambers for heavenly praise. The inhabitants of the sphere “beyond the stars” are way ahead of us but they invite us to join them in worshipping the Holy Trinity.

Herbert loved this perspective on prayer as already moving in the universe as we awake each morning [see verse 1: “the church’s banquet, angels age”]. We are never alone when praying; solitary worship is not possible since “you have come to thousands upon thousands of angels in joyful assembly” (Hebrews 12:22), and our every moment is passed in their company. Sing, intercede, give thanks and the great congregation “beyond the stars” open up their adoration to make room for ours. Thus in some of our services the scene is set:

Let us give thanks to the Lord our God…

Therefore with angels and archangels,

And with all the company of heaven

We proclaim your great and glorious name…

The Holy Spirit calls out all heaven for the “further exploration” into God. But in what sense can it be said that the Spirit’s “church-bells” are heard among us in the world? We can believe it because the same Holy Spirit “beyond the stars” also indwells his temple that is our bodies (1 Corinthians 6:19). The one Spirit creates one congregation of all in the universe who worship the Trinity. Spurgeon caught the heaven-on-earth dimension of our present life in his aphorism: “If you have the minimum in the Christian life, it will be enough to get you to heaven; if you have the maximum it will bring heaven to you on earth.” The maximum means we yield to the Spirit who orchestrates cosmic praise, ours on earth with theirs in heaven, taking both as one into Christ’s ceaseless prayer before the Father….

Consider the puzzling juxtaposition of “the Milky Way” in the previous image, with “beyond the stars.” If the stars (the Milky Way) are an image of prayer, what is Herbert hinting at when in the next line he takes us “beyond the stars.” The more I reflect upon this I can only think he is with deliberate design signalling a very different aspect of prayer…. Prayer “beyond the starts” refers to the times of spiritual emptiness and desolation we each of us have known to some extent. Like Job on his ash-heap, the Prodigal in his pigsty, Christ on Holy Saturday. It is an experience not much referred to from the pulpit, perhaps because it runs dead counter to the desires and ideals of our culture….

Not only do those times of spiritual emptiness occur to most of us, it seems they are crucial to growth and progress. God in his love for us deals only in truth and reality when confronting us with our emptiness, our limited powers of understanding, and our perverse ability to confine ourselves in falsehood. Yet even then, especially then, we can hear the Spirit’s voice, his “church-bells” in the darkness. Thus Job survived his ash-heap, Jonah escaped his whale, the wayward son returned to the joy of his father’s home, and Christ rose from the dead.

Prayer is also “the soul’s blood.”

What blood is to the body, prayer is to the soul (“God’s breath in man returning to his birth”). It would be foolish to describe physical blood as an “aspect” of bodily life for that life is inconceivable without it. Blood is the essence of life. Similarly, to call prayer the “soul’s blood” is to claim for it a pervasive power and authority in our personal life as a child of God. The converse is only too apparent, for where prayer is neglected the sense of God’s presence fades, we become spiritually enfeebled, burdened with unconfessed sin and anxieties, joy drains away and the Christian life declines into unreality. Or if we do retain the shape and outline of Christian life it lacks all grip and conviction.

I conclude with this analogy from the current coronavirus pandemic. It was recently reported that some laboratories are testing transfusions of “convalescent plasma” from COVID-19 survivors to current patients, an idea that goes back to the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic. This blood may stimulate antibodies much as vaccinations do. Anyway, suppose we think of the human soul as the victim of our sinful human condition. By faith and in prayer, Christ’s blood received spiritually in prayer and sacramentally in the Eucharist enhances our sick soul to hear the church-bells beyond the stars. Just a thought.

Photo: St. Andrew’s Church with Bell Tower, Bemerton

Day Fifteen

Church-bells beyond the stars heard, the soul’s blood,

The land of spices; something understood.

Prayer, George Herbert suggests, is a sensuous activity. By the time we finish the sonnet, he has appealed to our vision – “the Milky Way, the bird of Paradise,” “man well-drest” – our hearing – church bells beyond the stars,” “reversed thunder,” “a kind of tune” – our touch – “softness” – our taste – “the Church’s banquet,” “exalted manna” – and now, climactically and climatically, our smell – “the land of spices.”

Dennis Lennon continues in his concluding chapter:

What does prayer as the “land of spices” suggest to the imagination? Immense and rare riches from the East. It is an image of trafficking in the inexhaustible riches of Christ; a drawing upon his person, life, death and resurrection, his gift to us of the outpoured Holy Spirit, his ministry as mediator of the eternal covenant. It is an image of scripture’s great obsession:

Thanks be to God for his indescribable gift!… For you know the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, that though he was rich, yet for your sakes he became poor, so that you through his poverty might become rich… to grasp how wide and long and high and deep is the love of Christ, and to know this love that surpasses knowledge – that you may be filled to the measure of all the fulness of God … his incomparably great power for us who believe. That power is like the working of his mighty strength, which he exerted in Christ when he raised him from the dead … Christ, in whom are hidden all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge. (2 Corinthians 9:15 and 8:9; Ephesians 3:18 and 1:19-20; Colossians 2:2-3)

Those are but a sample of scripture’s celebration of God’s gift of his Son to the world. Prayer in the Holy Spirit opens up the believer to the immensities of Christ’s presence….

Prayer as “the land of spices” is not justification for a glib “prosperity gospel” religion. It is an image of our unbreakable and irreversible union with Christ.

For I am convinced that neither death nor life, neither angels nor demons, neither the present nor the future, nor any powers, neither height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God that is in Christ Jesus our Lord. (Romans 8:38-39)

Not least of the rich things are ours from the “land of spices” is a joyful freedom to take on whatever life or death can throw at us. That is the true healing, the true prosperity.

By prayer we travel to the “land of spices” on behalf of others. Just as those Renaissance navigators and traders made their extraordinary trips with shopping lists matched against market demands back in Europe, so we go to our boundlessly generous Lord Jesus for the needs of the world….

Finally, Lennon comes, rather briefly, to “something understood.”

With a sigh and a click the diamond is returned to the box. It has shown many extraordinary aspects of prayer, dazzling and enigmatic, ecstatic and contemplative, delighting and puzzling. Each of them is an encouragement that we go on with prayer, do the experiment of faith, follow the promises into God, bring the world to him for his healing. None more so than in these final two words, George Herbert’s sum total of the sonnet. Prayer is … “something understood.”

I promised a comment on the couplet completing the Shakespearean sonnet, Herbert’s final trick on the Bard himself. Instead of wrapping up the sonnet, the string of metaphors throughout the verses continues all the way into the last half-verse with “the land of spices”; and then we get the prosaic word pair: “something understood.” A couplet within a couplet!

“Something understood” is not a metaphor, it’s more like a proverb or a riddle, something like “’nuff said.” What does “something understood” mean? What is the “something” and who is understanding or being understood – God or us? I can’t help but hear the echo of St. Paul’s hymn to love:

For now we see in a mirror dimly, but then face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I have been fully known. (1Corinthians 13:12)

Lennon’s finale is equally concise and cryptic: “With a sigh and a click the diamond is returned to its box.” Having examined the diamond, we now return to everyday life, prosaic as it is, but perhaps with the heightened awareness of the gem God has given us in prayer.

***

I hope this little Lenten exercise has helped prepare you for the mighty acts which we celebrate in Holy Week and Easter.

Last year, I posted a “Easter Octave” of meditations which technically ran through Holy Week to Easter Day. I shall repost the Good Friday reading of George Herbert’s “The Sacrifice” next week on Maundy Thursday.

Photo: Casket Box (wallpaperflare).

Cover Photo: Diamond (pexels)