I preached this meditation at my parish church in Pennsylvania on Good Friday 1995

Then Jesus, crying with a loud voice, said, “Father, into thy hands I commit my spirit!” And having said this he breathed his last. (Luke 23:46)

Only two of Jesus’ words from the Cross are addressed to the Father on his own behalf:

“My God, my God, why hast Thou forsaken me?”

and

“Father, into thy hands I commit my spirit!”

On the surface, these words seem to express totally opposite sentiments. In the so-called cry of dereliction – “My God, my God…” – Jesus voices his sense of loss of the Father’s presence, while in the sixth word, which we are now considering, he seems to pray “in quiet confidence.” The cry of dereliction strikes us as harsh and shocking, while the latter prayer seems to portray Jesus as having come through his trial of faith and now entering into glory. There is some truth to this first impression of Jesus’ two personal petitions to the Father, but I think we miss the challenge of the present word if we jump too quickly to its comforting aspect.

First of all, notice that Jesus is not praying quietly. It says he “cried out with a loud voice.” In Luke’s Gospel at least, it is his death cry. Maybe it was a victory shout. John’s Gospel records Jesus as dying with the triumphant word “Finished!” on his lips. But the fact that “Father, into thy hands,” is a prayer, a petition, makes Jesus’ cry here in Luke much more problematical. It may be that our Lord was expressing here the same sense of loss of the Father’s presence that we find in the cry of dereliction.

Secondly, notice that in both cries from the Cross, Jesus is reciting from the psalms, in this case Psalm 31. The psalms, I often say, are not only the prayerbook of David, but also the prayerbook of Adam, that is, they incorporate the full range of emotions and experience known to humanity. What is fascinating is how often within one psalm, the pray-er moves from sentiments of loneliness and fear to confidence and joy. Both psalms that Jesus prayed from the Cross contain this movement.

Psalm 22 begins with “My God, my God, why hast Thou forsaken me?” but ends with the following:

You who fear the LORD, praise him!… For he has not despised or abhorred the affliction of the afflicted; and he has not hid his face from him, but has heard, when he cried to him. (Ps 22:23-24).

Similarly, the Psalmist who begins Psalm 31 with a word of trust “Into thy hands…” goes on to pray:

Be gracious to me, O Lord, for I am in distress; my eye is wasted from grief, my soul and my body also. For my life is spent with sorrow, and my years with sighing; my strength fails because of my misery, and my bones waste away. (Ps 31:9)

The way I see it, our Lord on the Cross did not vacillate in his feelings of fear and hope; rather, his prayers incorporate the full spectrum of the life of faith.

So let us look more exactly at what experience he was incorporating in these words. “Father, into thy hands I commit my spirit!” What does it mean that he was placing his “spirit,” i.e., his soul, in God’s hands?

One of the strangest little articles of the Apostles’ Creed says of Jesus that he “descended into hell.” This translation is somewhat misleading in that there is no biblical evidence that Jesus descended into the “lake of fire,” the place of final retribution of Satan and his allies. The Old Testament speaks of another place, called Sheol or Hades, where the souls of the departed dwell. It is to this place that Scripture says our Lord between his death and resurrection “preached to the spirits in prison” (1 Pet 3:19). And it is this reality, I believe, that Jesus was looking at when he prayed: “Father, into thy hands I commit my spirit!”

Now to grasp the depth of Jesus’ prayer, we should note that the place of departed spirits was not a pleasant place. From the biblical point of view, full humanity is a union of body and spirit, and death involves a breaking of that union. A human spirit without a body is a diminished creature. When a person dies, his body is immediately polluted by the corruption of death and his soul descends into oblivion, where David laments, “there is no remembrance of thee; [for] in Sheol who can give thee praise? (Ps 6:5).

Sheol is also a scary place because we know virtually nothing about it. It is that unknown land contemplated by Hamlet, from whose bourne no traveller returns. Job is bitterly realistic when he observes: “As the cloud fades and vanishes, so he who goes down to Sheol does not come up…” (Job 7:9). Solomon the Preacher questions: “Who knows whether the spirit of man goes upward and the spirit of the beast goes down into the earth?” (Ecclesiastes 3:21). In the Old Testament death is a one-way ticket to a shadowland, separated, maybe permanently, from the life and light of God. The idea of Paradise, I might add, was not taught in the Bible, and in any case was a place reserved for special heroes of the faith.

We should not immediately conclude that Jesus had any less sober view of the afterlife. Actually, he may have been more pessimistic than some Jews of his day, who believed they would have a separate compartment in Sheol — sort of like a first-class cabin — because they were Jews. But Jesus knew better, because he knew what was in the heart of man. He knew that the wages of sin is death and that all have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God. In this perspective, death is not only a one-way ticket, but we all travel in the baggage compartment!

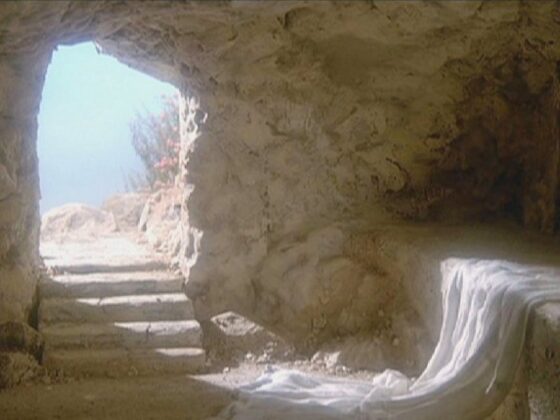

When Jesus cried out “Father, into thy hands I commit my spirit!” he could see in his mind’s eye his own lifeless body, hanging limply on the Cross. He could see the limbs tense up in rigor mortis; he could see them closing his staring eyes and tying his gaping jaw with a cloth. He could see them carrying his own corpse, with care and difficulty, down the hill of Golgotha to Joseph of Arimathea’s nearby tomb. He could see them anointing his body and wrapping it in a burial cloth. He could smell the spices meant to slow down putrefaction. He could see the stone roll closed over the mouth of the tomb. Then all went dark.

But darkness was not the end of it. When Jesus cried out “Father, into thy hands I commit my spirit!” he could imagine in the language of Scripture the destiny of his severed soul in the land of deep darkness. Up to this point, his human spirit had known the warm, nurturing darkness of a woman’s womb, but never before had it entered the cold nothingness of death. While all things were made by him, yet his soul had never known the torrents of chaos. While his embodied self had resisted the Tempter in the blazing desert, never before had his spirit been handed over to Satan’s power in deep darkness.

The Epistle to the Hebrews says that “in the days of his flesh, Jesus offered up prayers and supplications with loud cries and tears, to him who was able to save him from death, and he was heard for his godly fear” (Heb 5:7). Some of us have been at the point of death, or we have sat beside a loved one, praying that he or she would or would not die. What does it mean to say “he was heard”? It sure didn’t look like answered prayer on the first Good Friday.

We have come to know that God answers prayers when his greater purposes and glory are served. This does not stop us from asking why. Why did the Word made flesh, on whom the Spirit was abiding, have to go through the separation of soul and body? Was it not enough for Jesus to exhale his life-breath back to God the Father on Calvary? Was it not enough for Jesus suddenly to be caught back up into heaven like Enoch or Elijah, leaving a stunned centurion and an empty Cross?

No, this was not enough. From the last “giving up his Spirit” at 3pm on Good Friday to that night three days later when he breathed on the disciples anew, a transaction, a marvelous transaction was taking place in the history of the world, yes even in the history of God (if I can speak in that way). Just as the Godhead had once for all joined deity to humanity in the Virgin Birth, so this sinless Man had to be cracked in two like an earthen vessel in order to be a ransom for many. Without the separation of body and spirit, Jesus Christ could not be for us a merciful high priest, tempted in every way we have without sin. Without the burying in the tomb of the body of flesh and the descent into hell of Jesus’ soul, he could not emerge as the New Adam, a life-giving Spirit.

Jesus’ cries from the Cross were apparently not heard. Why? The answer is simple. It was for our sake. C. S. Lewis has likened the work of Jesus Christ to that of a diver

stripping off garment after garment, making himself naked, then flashing for a moment in the air, and then down through the green, and warm, and sunlit water into the pitch-black, cold, freezing water, and then at last out into the sunshine, holding in his hand the dripping thing he went down to get. This thing is human nature; but, associated with it, all Nature, the new universe.

If I could extend the metaphor one step further, when the divine diver breaks the surface the water, the sunshine that greets him is the a new sunshine, the light of heaven, and the air he gasps into his lungs is not the old, stale air of earth but the new ether of eternal life. Jesus, having given up the ghost on the Cross, now breathes his Holy Spirit on his disciples and they are born again from above.

When Jesus breathed out his last breath, he offered us the last best hope that our own lives will not end in vanity.

I have some family portraits on my wall at home. One is of my grandfather, who died in 1905. I never met him, and even my father did not tell me much about him. I do not believe there is anyone now alive who knew him. My father died 17 years ago. I do remember him well, but my children do not. After I die, they will have photographs and some family stories, but he will be only the vaguest name to their children.

Now let your imagination go forward a hundred years. In the year of our Lord 2095, every person here will be dead and buried. Most of our children will be dead also, and their children will remember us no better than we remember our ancestors. All of us, our grandparents, parents, children, grandchildren — and we ourselves will be nothing but corpses: some buried in coffins, some cremated, all returning to the inorganic elements which the Bible calls “dust.”

Each one of us, whether we are old or young, rich or poor, happy or unhappy, will face that moment when we will “commit our Spirit” into the darkness and bequeath our bodies to decay and death. Jesus’ final prayer is an assurance that God himself has passed through that awesome moment. It is also a reminder that our souls and spirits do not cease to be but continue on in expectation of a final day when He shall judge the quick and the dead. And it is a challenge that only as we commit our spirits to the heavenly Father through his crucified and risen Son can we approach that Day with confidence and joy.

The challenge and comfort of Jesus’ dying prayer from the Cross is this: It is not as it seems. Our bodies may rot, but our spirits live on. Not in the idealistic sense like John Brown’s body, which lies a-mouldering in the ground waiting for vindication of some great cause, but int the merciful and confident sense of H.F. Lyte’s final hymn.

Swift to its close ebbs out life’s little day,

Earth’s joys grow dim, its glories pass away,

Change and decay in all around I see;

O thou who changest not, abide with me.

Hold thou thy cross before my closing eyes;

Shine through the gloom and point me to the skies;

Heaven’s morning breaks, and earth’s vain shadows flee:

In life, in death, O Lord, abide with me.

Collect for Holy Saturday

O God, Creator of heaven and earth: Grant that, as the crucified body of your dear Son was laid in the tomb and rested on this holy Sabbath, so we may await with him the coming of the third day, and rise with him to newness of life; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Today’s hymn is In Christ Alone, by Keith and Krysten Getty.

Cover Art is Tintoretto, The Descent into Hell.